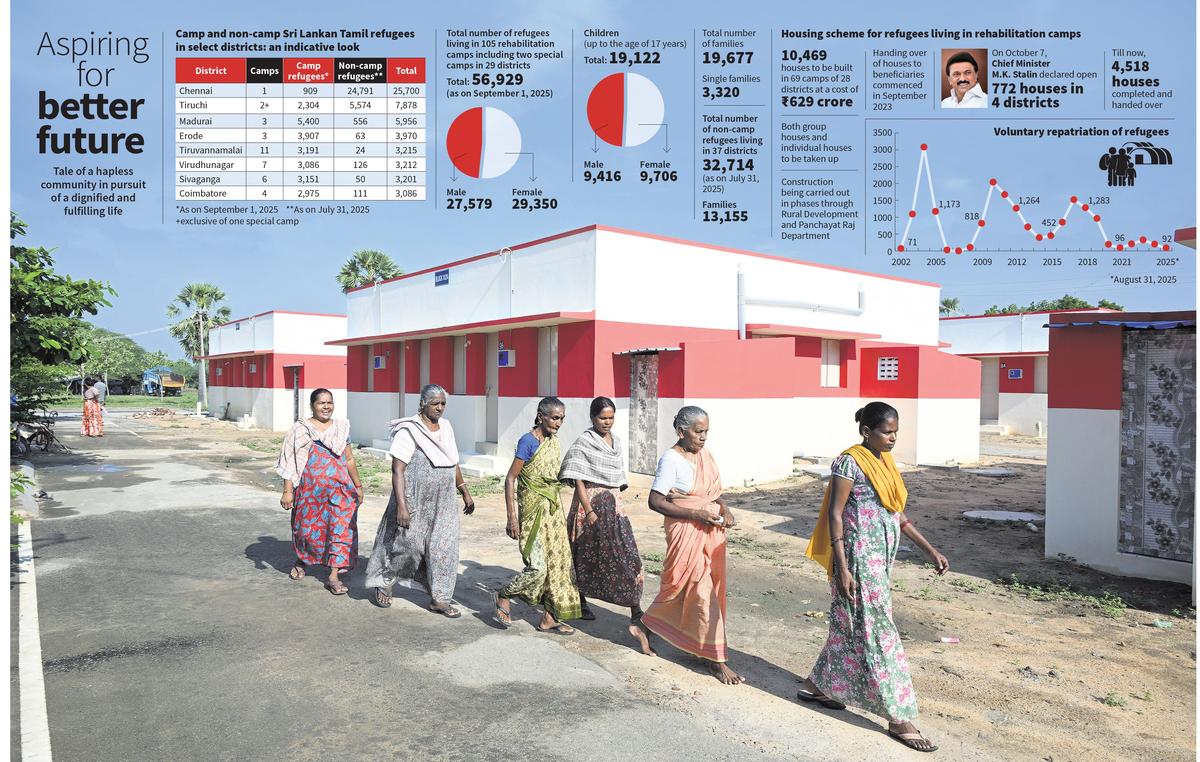

N. Leena, a young refugee living in a rehabilitation camp for Sri Lankan Tamils in Thoothukudi district, S. Dilakshana, another young refugee in Sivaganga, and Inbamalar, a middle-aged woman at a rehabilitation camp in Virudhunagar, have been feeling a renewed sense of hope. They were among those who benefited from the 772 new houses inaugurated by Chief Minister M. K. Stalin for camp refugees on October 7. At last, they have better shelter protecting them from the vagaries of nature. What makes them doubly happy is the gazette notification of the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), dated September 1, which had regularised the entry and stay of undocumented or overstaying Sri Lankan Tamil refugees who entered the country before January 9, 2015.

Both Ms. Leena and Ms. Dilakshana were born in Tamil Nadu — the former in Thoothukudi and the latter in Sivaganga — while Ms. Inbamalar migrated from Jaffna district in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka in 1990, when the civil war between Tamil rebels and the Sri Lankan security forces had resumed after a brief truce.

Tin sheets and thatched roof

“Initially, we refugees were put up in houses made of tin sheets [thatched roof houses, too, were provided]. Over a period of time, the houses improved,” says Ms. Inbamalar, who lives in Mallankinaru of Virudhunagar, thanking the present Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) government for the way it has been enhancing the quality of life of the refugees. Skill development training and mental health awareness programmes are the latest initiatives being implemented for them.

The MHA releases funds to the State government for sharing the cost of relief and other measures. Its annual report for 2023-24 states that the Union government spent about ₹1,375 crore for providing relief and accommodation to these refugees during the period between July 1983 and June 2024.

For Thayalini, who lives in the Thappathi camp in Thoothukudi, about 13 km from Ettayapuram, life has been more stressful than others. She has experienced displacement several times ever since she came to the State as a six-year-old in 1990. In a sense, getting a permanent, quality shelter has made her happier, as she had suffered hardship on account of various factors, including lack of proper shelter. Recalling that they were concerned over facilities for the discharge of domestic sewage and rainwater, in view of similar problems reported in a camp at Dindigul, the refugees in many new camps are relieved that the same is not the case now. R. Jayachandran, who resides at a rehabilitation camp in Sorakolathur, about 15 km from Tiruvannamalai town, came to Tamil Nadu in 1990 when he was 12. As a key person in his camp, Mr. Jayachandran has been closely following the developments regarding refugees in general. “In my camp, we have discussed the implications of the MHA’s notification. Definitely, it is a step forward,” he observes.

It is not only in Sorakolathur but also in all other camps that the Union government’s decision has been positively viewed by the refugees, even though many tend to view the notification as one that takes away the tag of “illegal migrants” for them. Actually, the order has given exemption to the undocumented or overstaying refugees from Sub-sections 1, 2, and 3 of Section 3 (requirement of passport or other travel document and visa) of the Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025. Under the law that came into force in April, the entry and stay of foreigners without passport or valid documents has been made punishable by a fine of ₹5 lakh or up to five years imprisonment or both. The Act has subsumed four laws — the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920; the Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939; the Foreigners Act, 1946; and the Immigration (Carriers’ Liability) Act, 2000.

The notification’s critical element for the exemption of penal provisions is that the refugees should have been registered with the authorities concerned. However, there are some, especially non-camp refugees, who have not been able to renew their registration for one reason or the other, and, who have, as per the understanding of the officials concerned, become unregistered persons. These persons are not eligible for the relief, even if they have been in India much before January 9, 2015, the date specified in the notification.

Time-consuming procedure

The option before these unregistered persons is that they have to go back to Sri Lanka after obtaining an exit visa from the authorities, a procedure that may take a few months, and it is from there that they need to apply for a visa from the High Commission of India in the neighbouring country. The probability of hassle-free process in Sri Lanka for those returnees seems to be low, as immigration officials may subject them to prolonged questioning. There would not be any purpose in going there, says a non-camp refugee, who had to migrate to India in the mid-1980s after the 1983 anti-Tamil pogrom.

Even though this “unregistered refugee” even has a full-fledged Sri Lankan passport issued through the Deputy High Commission of Sri Lanka in Chennai — an arrangement that is no longer in existence — he is not in a position to use it as the document does not carry any visa entry. He is conscious of the fact that India, despite not being a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol, has been following the principle of non-refoulement (bar on states from forcibly repatriating persons to the countries of their origin when there are substantial grounds to conclude that such persons would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return). Yet, the middle-aged refugee, who does not want to be identified, is anxious to remove the uncertainty surrounding him and his family.

Notwithstanding its nature of providing limited relief to the registered refugees, the notification has made both subject experts and critics of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party at the Centre react more or less in a similar fashion. All have expressed the hope that this will pave the way for the refugees to get Indian citizenship. An expert recalls that before citizenship was provided, through the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) of 2019, to six religious minorities (Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians) belonging to Bangladesh and Pakistan who entered India on or before December 31, 2014), the refugees were first given a similar relief, by a notification of September 7, 2015. At that time, the treatment was provided by exempting them from the relevant legal provisions. Afghanistan was later included during the enactment of the CAA, 2019.

Former presidents of the State unit of the BJP, Union Minister L. Murugan and K. Annamalai, said on their respective social media handles in early September that the development was just one step away from granting citizenship to the refugees. Welcoming the measure and claiming credit on behalf of the DMK, the party’s deputy general secretary and MP, Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, however, felt that “true justice is yet to be done”. She contended that “the arbitrary cut-off date excludes” many who arrived later due to persecution. The “continued denial of a pathway to citizenship” left their struggle “incomplete”, she mentioned in her post.

Cutting across places of their origin in Sri Lanka, the refugees interviewed by this journalist emphatically said that getting citizenship alone will provide them a “permanent solution” to their problems. Only such a move would make livelihood opportunities better for the youth. Invariably, as all young refugees get undergraduate (UG) degrees or diplomas, they face many stumbling blocks in their career. Giving a course-wise break-down of refugee-students, the Commissionerate of Rehabilitation and Welfare of Non-Resident Tamils, in its reply in July this year under the Right to Information Act, stated that during 2023-24 and 2024-25, the number of engineering UG students was 188 and 193 respectively; arts and science UG courses 1,150 and 1,152; diploma courses 245 and 191; and technical courses 246 and 384.

Ms. Dilakshana, who holds a degree in information technology, is sore that unlike her friends, she is unable to sit for competitive examinations, including those conducted by the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission (TNPSC). “That I am a refugee is the only factor going against me. Otherwise, I am as keen as others in preparing and appearing for the examinations. If given an opportunity, I will do well,” the young mother of two says. Ms. Leena too echoes her feelings.

The refugee tag, which does not make them comfortable, comes in the way of the youth aspiring for jobs that suit their educational qualifications. “Though a handful of persons from our community have been able to join IT firms, a majority in the productive age group are daily wage earners,” Thangeswaran, a resident of Thottanuthu camp in Dindigul, says, adding that even those who hold engineering degrees go to bigger cities such as Coimbatore for work but return to the camps as they are not able to stay there for long.

Periodic head count

One of the reasons is the stipulation that camp refugees have to be present in person at the time of periodical head count. It is for this purpose that they have to take a break from work and be present in the camps, he explains, adding that this creates practical difficulties. Ultimately, painting and carpentry are some of the jobs that the refugees, in general, take up.

The Union government’s principled position is that those eligible can obtain citizenship either by registration or by naturalisation. But, most of the refugees are regarded as illegal migrants, the condition which renders them ineligible for citizenship. This is why the latest notification has given them the hope of getting Indian citizenship, as it happened in case of the six minority groups of the three south Asian countries who ceased to be called illegal migrants under the CAA, 2019. Before the Act, they were exempted from the penal provisions. Though the refugees have endured pain for long, the executive and the judiciary have been empathetic. The State government, which has been taking a number of measures to enable the refugees to lead lives with dignity, is receptive to the idea of doing much more, amid constraints. In the last six to seven years, the Madras High Court has gone to the rescue of refugees and ensured citizenship to some within the legal parameters.

The Sri Lankan refugees know the road ahead is not so simple and easy, especially in their pursuit of Indian citizenship. A substantial number of them claim that their ancestors had all gone from Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka for employment in tea plantations in the past 200 years, making them eligible for citizenship. Others point out that having been born and brought up in Tamil Nadu and accustomed to the way of life in the State, they consider Sri Lanka as alien as any other country. Despite their life stories being complex, the young refugees have not lost hope in the Indian state and they are optimistic of getting Indian citizenship at least for their inheritors, if not for themselves.