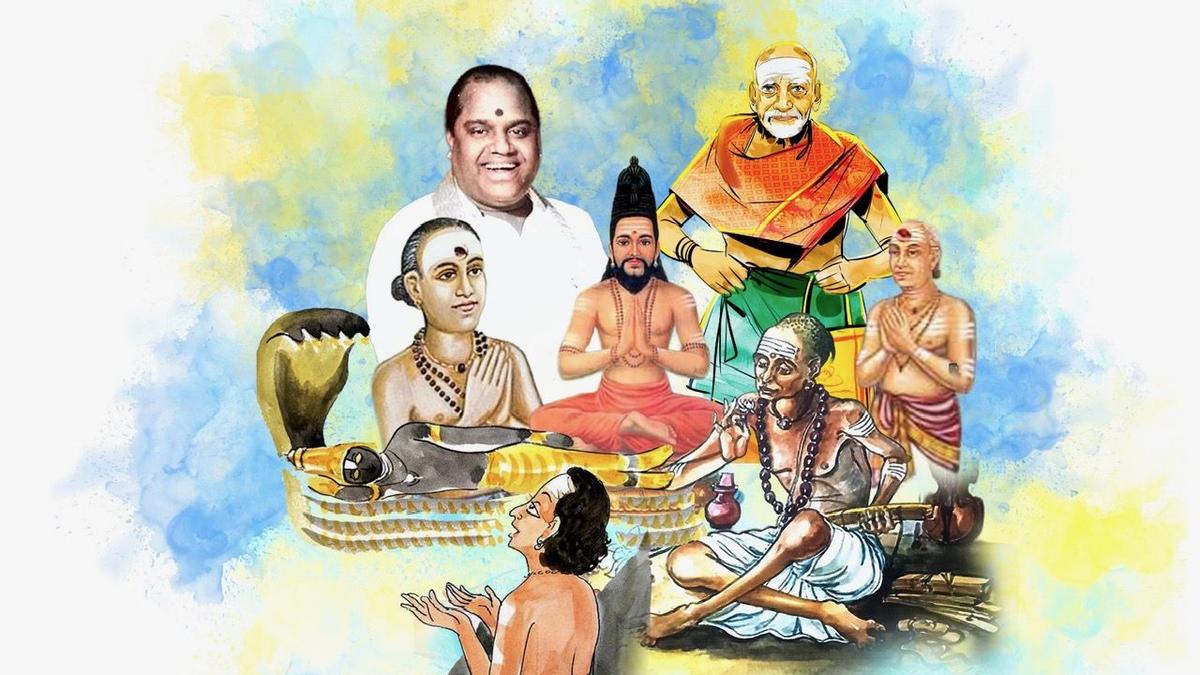

Remembering the composers who enriched the Carnatic music repertoire with their Tamil songs

| Photo Credit: Joseph Gnana Sathish

During the height of the Tamil Isai movement, when Sabhas, musicians and patrons were daggers drawn and hurling imprecations at each other, the Madras Music Academy invited Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar to deliver a speech under the title ‘Sangita and Sahitya.’ This was during the 1941 annual conference and the talk was delivered on December 29.

Ramanuja Iyengar, who had probably done more than any other musician for Tamil songs on the Carnatic platform, was of the view that “the language controversy had no place at all in the field of aesthetic music and would do it no good”. In this, he and the Madras Music Academy were of one mind. He then went on to highlight the inadequate repertoire then existing in Tamil, which forced most musicians to sing the pieces in the post Ragam Tanam Pallavi phase of a concert.

“Compositions such as the Tevaram, the Tiruvachakam, the Tiruttandagam and Tiruppugazh were in the form of Kannigal and not kirtanas with pallavi, anupallavi and charanam,” he said.

It was interesting that Ramanuja Iyengar, of all people, had made this statement, for he had popularised the compositions of Arunachala Kavi’s Rama Natakam. Others of his generation were singing the works of composers such as Marimutha Pillai, Muthu Thandavar and Gopalakrishna Bharati, all of which were in the kirtana format. And so, at least from the 18th century, Tamil too had adapted to suit the three-part structure that had come to define Carnatic music from the 16th century or so. For, prior to this, we seem to have only compositions with pallavi and charanam-s, a format that seems to have existed across South India.

For a language that had almost a continuous association with music since the Silapathikaram, Tamil seems to have been a victim of more format than form. And there were historic reasons for it. The language ceased being that of the administration from the time of the Vijayanagar empire, and more so with the Nayaks, who, with a view to reinforcing their claim to kingship, commissioned compositions in Telugu. The Marathas who followed, simply followed the trend, and so, between the 15th and 19th centuries, Telugu, with Sanskrit as a distant second, was the language of choice for music. It was only the composers in these languages who attracted students as well, for singing these works in the courts of patrons was a sure path to success. Tyagaraja eschewed patronage but not so most of his students and their disciples.

During this phase, composing in Tamil did not cease. But the musicians who did so had no lineage to pass their works to posterity. We do not read of disciples for Marimutha Pillai or Muthu Thandavar. Arunachala Kavi’s Rama Natakam was tuned essentially by his two disciples, but they do not seem to have had anybody carrying on the tradition. Ghanam Krishna Iyer and the Anai Ayya brothers did create songs in Tamil but that their tunes survived was more an exception. Even more surprising is that the Nandanar Charittiram of Gopalakrishna Bharathi, though such a success in its time, lost all its music by the early 20th century and had to be reset. The same fate befell others such as Mazhavai Chidambara Bharathi and Kavi Kunjara Bharathi.

It is in this context that we need to laud the visionaries who launched the Tamil Isai (more correctly the Tamil Song) Movement, spurred by the writings of Kalki Krishnamurthy and bankrolled essentially by Raja Sir Annamalai Chettiar. On the one hand, there was a serious exercise in setting to music works of the past and publishing them in notation. On the other, there was encouragement to compose, by way of competitions and the establishment of a college at Chidambaram, which would be the core of the Annamalai University. It was here that musicians such as Sangita Kalanidhi-s Tiger Varadachariar and K. Ponniah Pillai, and other stalwarts such as M.M. Dhandapani Desigar would create their own songs. Lyrics of others such as Periyasami Thooran too were set to music.

There were some who were outside this ecosystem. Nilakanta Sivan, Papanasam Sivan and Koteeswara Iyer are names that spring to mind. In the case of Papanasam Sivan, cinema was a reason for a few of his songs, but the majority were more out of a love for the language, which incidentally, he mastered a little late in life! Taken all in all, the 20th century has been kinder to Tamil in Carnatic Music, and the language has come to stay. That said, very few musicians whose mother tongue is not Tamil sing in the language while the opposite is not true.

The politics surrounding it apart, what emerged from the Tamil Song Movement was for the greater good. And in saying it would do no good, Ramanuja Iyengar was way off the mark.

Published – December 04, 2025 11:44 am IST