The English writer C.P. Snow argued in 1959 that modern intellectual life had split into two camps. Literary intellectuals were arrayed on one side and scientists on the other, separated by what Snow called a “gulf of mutual incomprehension”. He worried that this divide damaged public life because each group dismissed what the other knew and valued. Many readers have seen Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia, and especially now after his death on November 29, as a work that probes that divide. A closer look, however, reveals that Arcadia actually rejects Snow’s thesis.

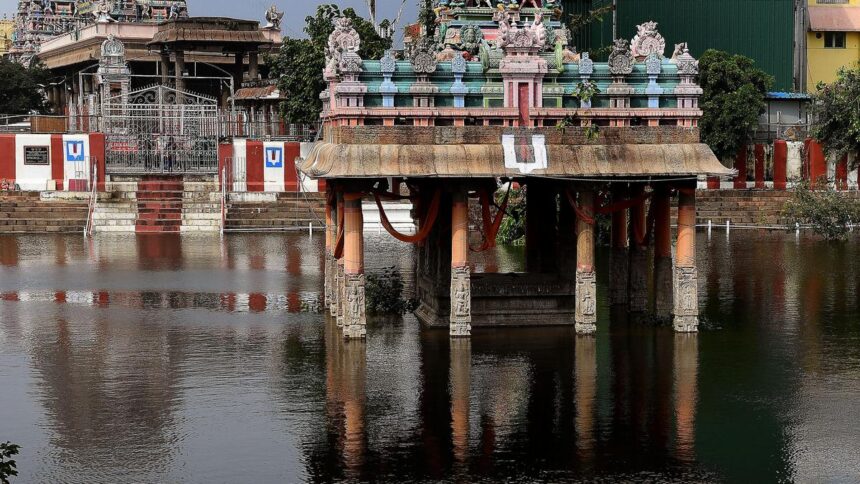

The play moves between two periods in the same English country house, Sidley Park. In the early 1800s, a young girl named Thomasina Coverly studies with her tutor, Septimus Hodge. In the late 20th century, a group of researchers tries to piece together what happened in those years: they’re especially interested in a solitary figure who later lived in a small lodge on the property.

In the 19th-century scenes, the divide between the “cultures” has still to calcify — and yet the audience can already sense the pressures that will later feed Snow’s diagnosis. Septimus is a classical tutor steeped in Latin, poetry, and Newtonian mechanics. Thomasina is his pupil but she’s also an early scientist in everything but name, inventing the first methods for calculation and thinking about why some processes in nature can’t be reversed. She reads poets and performs advanced calculations at the same table.

Tom Stoppard at a showing of Arcadia in New York City, 2011.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The 20th-century strand of the play comes closer to Snow’s picture of the two opposed camps. Valentine Coverly is a scientist who works on mathematical models and stands for contemporary number-driven work. He writes code and discusses chaos theory. Bernard, the literary scholar, cares about style and showmanship and he openly sneers at physics and cosmology in terms very close to the attitudes Snow described. Hannah, the historian of ideas, sits between them. She isn’t a scientist but she insists on evidence and is suspicious of Bernard’s romantic narrative.

Snow’s picture helps to clarify why those modern scenes feel like a clash of outlooks and not just of personalities. Bernard embodies a “traditional culture” that treats science as marginal to questions of meaning whereas Valentine embodies the sort of scientific literacy Snow thought public life needed but lacked.

Quests for meaning

But Arcadia doesn’t just restate Snow. It shows that the simple opposition breaks down when you look closer. Thomasina’s work is pure mathematics yet it’s driven by curiosity about rabbits and rice pudding. Septimus is a man of letters who spends his later life on long, lonely calculations. Within the play’s local legend, the “hermit” first appears as a familiar Romantic figure — a half-mad sage who has withdrawn from society to brood over unworldly questions. His is exactly the kind of figure Snow might have grouped with poets and sages, but what the “hermit” actually leaves behind is a carefully worked-out pattern of numbers. Stoppard’s choice thus shows that intense, solitary quests for meaning can take mathematical forms as well, not just literary or philosophical ones.

Dan Stevens as Septimus Hodge and Jessie Cave as Thomasina Coverly in a production of Arcadia, directed by David Leveaux, at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

In fact, the way Arcadia uses its setting — a single room — also cuts through Snow’s gap between cultures. The same table in the room hosts Thomasina’s equations, Septimus’s translations, Valentine’s code printouts, Hannah’s notebooks, and Bernard’s lecture script. This Stoppardian staging isn’t accidental but insists these activities share a physical and social space. Thematically, too, both the historical and the modern storylines deal with the same problems: of incomplete evidence and the difficulties of recovering the past.

Readers and critics have also linked the play to late-20th century ideas about chaos and irreversibility. In his 1987 book Chaos: Making a New Science, for instance, the American author James Gleick introduces readers to the new ways scientists describe complex behaviour. (Stoppard has said this book inspired him to write Arcadia.) “Gleick wrote about wondrous mathematical entities called strange attractors and fractals and, importantly, about how these ideas weren’t limited to physics or mathematics. They shaped how people thought about weather, populations, even the way a dripping tap behaves. For Gleick, chaos was a set of tools that, once they’d matured, could frolic through different fields. That’s exactly the kind of movement that plays out in miniature at Sidley Park.

A scene from David Leveaux’s production of Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London, 2009.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

In their 1984 book Order Out of Chaos, the Belgian chemist Ilya Prigogine and Belgian philosopher Isabelle Stengers had gone further in a different direction, as University of Sheffield scholar Gemma Curto found last year. Prigogine and Stengers had argued that modern physics and chemistry had forced science to take time and irreversibility seriously. Many older theories treated the most basic laws as timeless and reversible, and pushed questions of disorder to the margins. But Prigogine and Stengers insisted that processes that can’t be reversed and systems far from equilibrium really belonged at the centre. And from this they concluded that scientific work isn’t a march towards a single, detached view of reality. Instead, it’s an ongoing, historical conversation between humans and the world they study. Scientific concepts emerge at particular moments, in response to particular problems, then spread into wider culture.

No two cultures

Against this backdrop, it becomes clear that Arcadia’s talk of entropy and chaos is filtered through maths lessons, landscape design, literary criticism, and local legend. They’re all part of how its characters argue about taste, responsibility, and loss, in exactly the kind of cross-field travel Gleick chronicled and the historical circulation Prigogine and Stengers described. They show that concepts born in physics and mathematics aren’t destined to stay in a sealed compartment. Instead, if they’re allowed, they can become part of a shared cultural vocabulary that shapes how people talk about time and history and change.

Thus Snow’s conception bears on Arcadia by sharpening the modern-day conflicts between Bernard, Hannah, and Valentine, where the fault line between literary performance and quantitative modelling is explicit — and by providing a useful contrast with the 19th-century material, where that line hasn’t yet hardened and Thomasina and Septimus still inhabit a mixed intellectual world.

At the same time, the way Stoppard handles the “hermit” and Thomasina’s work undermines the idea that “science” equals cold, outward order while “the humanities” equals passions and inwardness. The play’s core runs through a set of calculations that never reach their intended audience, as if to say solitary quests for meaning can be mathematical as well as literary. In this sense, Arcadia uses Snow’s divide to frame its conflicts but finally pushes back against it, showing that the ways in which people seek understanding can’t be cleanly separated into two cultures.

mukunth.v@thehindu.co.in

Published – December 04, 2025 03:05 pm IST