For the first few weeks after they returned to Hyderabad in 2019, Padma Priya, 39, and her husband would stare into the blue sky in awe. They had stopped looking at the sky during winters in their five years of living in Delhi. “Either it was not visible due to the smog or it was this dirty grey,” says the media consultant.

They moved cities so that their daughter could breathe easy. Ever since her birth, she would fall sick frequently; by the age of 2, she had three bouts of bronchitis. As parents they did everything they could, from buying air purifiers to restricting outdoor exposure, but her breathing issues persisted. “By the age of 3, she already knew how to hold the nebuliser,” says Padma Priya, who had to quit her communications job owing to the frequent leaves she needed for managing their daughter’s health.

Padma Priya remembers one scary night in 2017, when their daughter was breathless, coughing for over 40 minutes straight. The paediatric pulmonologist recommended steroids and antibiotics and asked the question that changed their life trajectory — is there any way that they could move out of the city? Since their daughter was under the age of five, he told them that her lungs could still recover, else she would develop asthma and need inhalers all her life. The couple took the difficult decision to leave, paring down expenses and opting for a small 2BHK in Hyderabad. “It was a gamble but it was better than getting our daughter susceptible to lifelong breathing issues,” she says. Within a few weeks of moving, the little girl’s health improved. They have never regretted their decision.

Six years ago, this kind of move was unheard of. Old-time Delhi residents sneered at those who wore masks due to smog. Now, amid talks of climate change, moving out of the city is becoming a strange new reality. A growing section of people — concerned parents, those facing debilitating health issues, young professionals with remote jobs — is opting to counter the impact of air pollution by leaving the city, either temporarily or permanently. They are being called “smog refugees”.

According to a new survey by consumer insights platform Smytten PulseAI, about 34.6% of the 4,000 residents surveyed in Delhi NCR are considering moving out of the region, due to deteriorating air, for their family’s health and future.

This trend of ‘air-pollution exodus’ is neither new nor restricted to Delhi. Migration fuelled by extreme weather events or environmental degradation has been well observed globally and several studies show that air pollution is one of the key factors leading to migration. A 2023 study, published in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, based on China Labour Force Dynamics Survey data, showed if the level of PM2.5 (particulate matter less than 2.5 micrometres, a measure of air quality) increases by 10µg/m3, the probability of migrants coming into the city will be reduced by 21.2%. Such studies have also shown that when the air quality deteriorates, it’s the highly educated and skilled workers who are the first ones to relocate. That is the case with Delhi NCR. This kind of migration not just shapes the labour market but also deepens economic inequality.

‘The poison in our air’

Several contributing factors have turned the Delhi NCR region into a ‘gas chamber’: Delhi sits in the majorly land-locked Indo-Gangetic Plains surrounded by other polluted States while lacking strong sea breezes that help cities like Mumbai or Chennai. Further, winter air traps pollution, heavy local emissions and smoke from outside the city, creating prolonged PM2.5 spikes, which are worse than other cities. An average Delhi resident can lose up to 10 years of their life due to poor air, a 2022 study by Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago showed.

Delhi’s air pollution remains high, among the worst globally, averaging more than 100µg/m3 for at least 15 years.

While there has been some improvement in the recent years, Delhi’s air pollution remains high, averaging more than 100µg/m3 for at least 15 years, and is among the worst globally. The air quality was in the extremely bad range in the early to mid-2010s, peaking around 2015-16, but residents mistook smog for winter fog. There has been gradual improvement after 2018, even though it remains in the “unhealthy” range most of the year.

Through judicial rulings and strict policy measures implemented between 1998 and 2018 — like banning pet coke, furnace oil, coal industry and shifting diesel fleet to CNG — there has been a gradual decline of the city’s air pollution but it still requires 60% further reduction to meet the cleaner standards, says Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director, research & advocacy, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), Delhi.

In 2024, the annual average of PM2.5 level in Delhi was 104.7µg/m3, according to a CSE assessment, more than twice the national ambient air quality standard (40µg/m3) and 20 times the WHO guidelines (5µg/m3). PM2.5 particles are 30 times thinner than a strand of hair and can enter the bloodstream and cause strokes, heart attacks and respiratory diseases like asthma, COPD, bronchitis and pneumonia. Exposure to PM2.5 levels is linked with 3.8 million deaths during 2009-19 in India (report published in Lancet 2024), along with the risk for pre-term and underweight birth weight, lung cancer and diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure.

An NDMC (New Delhi Municipal Corporation) fire service van spraying water on trees and pavements in Central Delhi to check the dust pollution.

| Photo Credit:

Naveen Macro

Roychowdhury adds, the lesson from Beijing’s successful clean air transformation (2013-17) is that this cannot be achieved through emergency measures such as the government’s Graded Response Action Plan aka GRAP I, II, III, but would “require energy transition towards clean fuel in industry, adoption of zero-emission electric vehicles, and the elimination of waste-burning at scale and speed across not just Delhi NCR but also the entire Indo-Gangetic Plains”. No one city can clean up on its own.

In the last 30 years, there has been a dramatic shift in the demographic affected by lung cancer, says Dr. Arvind Kumar, founder trustee, Lung Care Foundation, Delhi, and chairman, Institute of Chest Surgery, Medanta Hospital, Gurugram. He says, earlier 90% of lung cancer patients were smokers, mostly men in their 50s and 60s, while today, half are non-smokers, with nearly 40% being women, in their 30s and 40s. “During surgery, we now find black deposits even in young non-smokers which is a change that strongly correlates with long-term exposure to polluted air,” he says.

To save the children

Gurugram resident Anjali (name changed) and her husband, too, could not imagine their two-and-a-half-year-old daughter growing up breathing the poisonous air.

The 39-year-old IT consultant, a daily 5-10 km runner, started noticing how her throat began to itch and her heart rate increased within the first 2 km itself. Anjali started reading up on pollution and decided that long vacations in the winter wouldn’t help any longer. The couple is all set to move 2,500 km away to Kerala, to a suburb of Kochi, where her husband hails from. She has a remote job and will have to adjust to the place’s language and lifestyle. Her husband, who works in a hybrid set-up, is yet to reveal to his company the planned move and is banking on his accumulated leave.

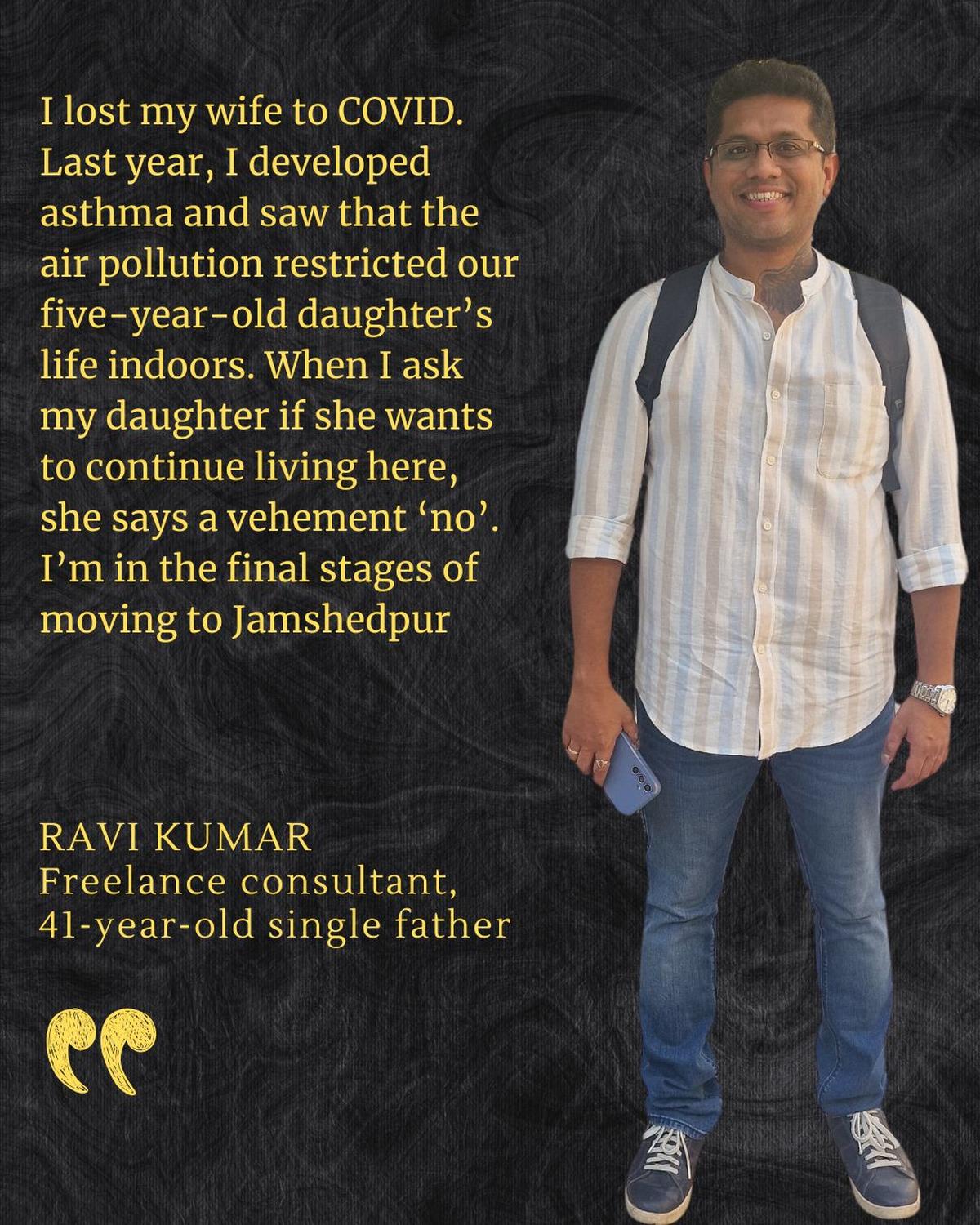

For freelance consultant Ravi Verma, 41, the decision to leave Delhi has been quietly simmering over 10 years, and was exacerbated by the loss of his wife and close relatives during COVID-19. After spending his childhood in close-knit Bokaro, Verma always wanted to move back to a small town. The single father to a five-year-old daughter sees no reason in living in a city that does not offer even a basic quality of life. “Your decisions are shaped by what’s best for your child,” he says.

Last year, Verma developed asthma and observed how air pollution restricted his child’s life indoors. “When I ask my daughter if you want to continue living here, she says a vehement no,” he says. Verma is in the final stages of moving to Jamshedpur — getting his home ready and securing school admission for his daughter.

The Smytten PulseAI survey shows that among those considering relocation, nearly 50% prefer a 1 to 3-year relocation window. For Verma, the process of planning and saving started years ago. He advises others to make the decision wisely based on their financial status and responsibilities. “The cost of relocation itself comes to lakhs of rupees and even with lower cost of living, there are expenses which one has to consider before taking the plunge,” he says.

Government apathy

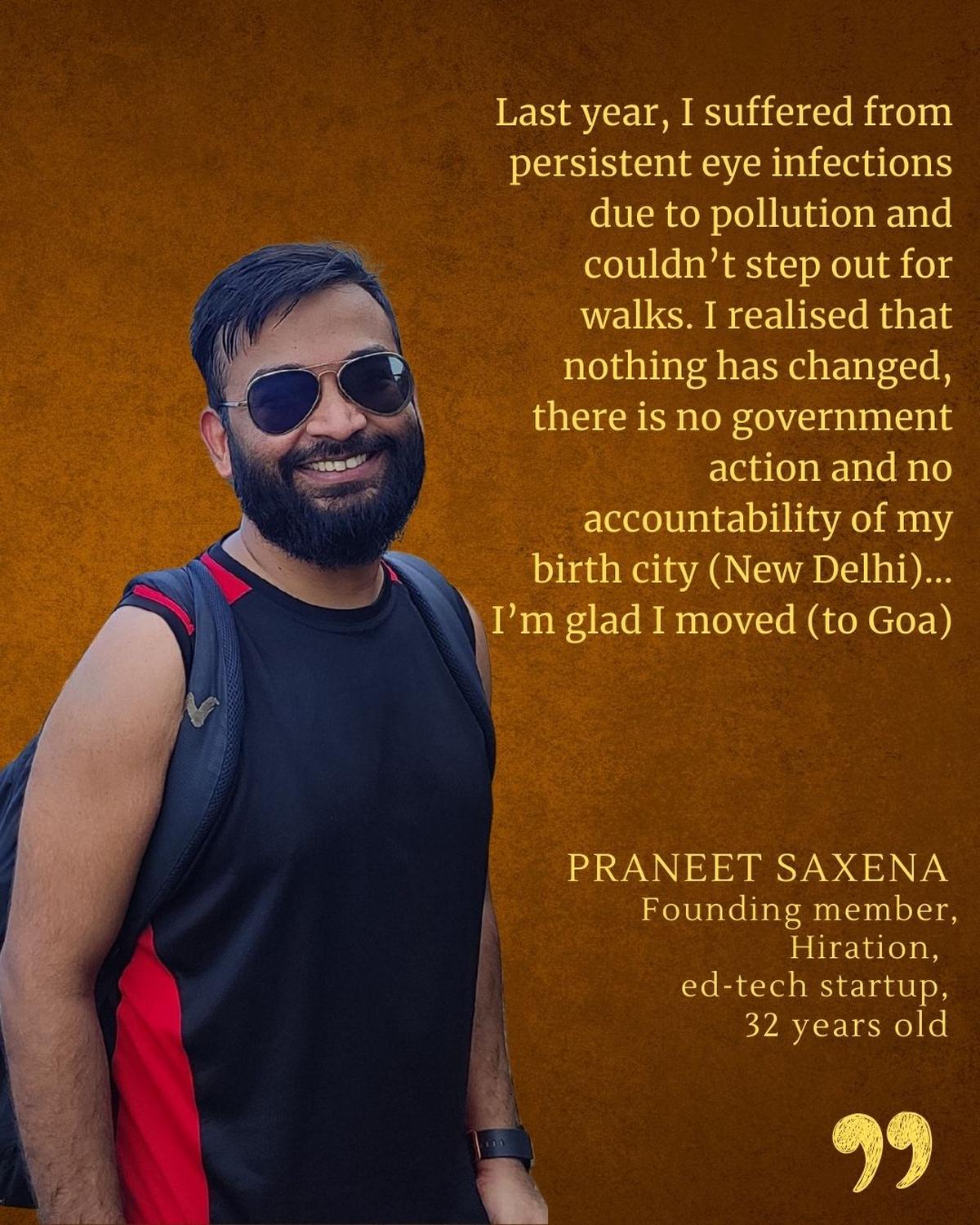

For 32-year-old Praneet Saxena, founding member of Hiration, an ed-tech startup, it was not an easy decision to leave his birth city. Having spent a few months with his brother in Berlin and with parents in Bhopal, when he returned to Delhi in November 2024, he suffered from persistent eye infections due to pollution and could not step out for walks. “I realised that nothing has changed, there is no government action and no accountability,” he says. Looking back, he’s glad he got out of the city since the Supreme Court lifted the firecracker ban this year and made its decision that opens up 90% of Aravalli range for mining and construction.

View of a fog-covered road in Central Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Prabhas Roy

Toying with the idea of Bengaluru, he moved to Goa within a month, because his friend was renting out his apartment. “There are problems of mining and deforestation even in Goa but the quality of life is overall still better,” he says. While he misses Delhi friends, food and the theatre and music circuit, in Goa, he has found greenery, nature and blue skies. Saxena believes this kind of migration is no longer a choice for only those with remote jobs; when the three-month-old daughter of his best friend, also an HR-tech startup co-founder, developed breathing issues in Delhi, the family had to temporarily move to Saxena’s Goa apartment this winter.

Whose air is it anyway?

While children with respiratory and cardiac issues and senior citizens are vulnerable across classes, more vulnerable are the malnourished, occupationally exposed low-income groups. Poornima Prabhakaran, director, Centre for Health Analytics Research and Trends, Ashoka University, concurs, “Only a very small section of people can afford to relocate because of air pollution; a large section of Delhi residents belongs to the working class, outdoor labourers, daily wage workers, who have no choice but to stay on here and are the most vulnerable groups to the impact of air pollution.”

A pedestrian wearing a face mask walks past the Akshardham Temple amid morning smog ahead of Diwali in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Subhash Paul

Crowded and dirty street; a worker cleaning the road in Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Nikada

Smoke billows from the burning landfill site in Ghazipur, in East Delhi, while excavators and fire tender trying to douse the fire.

| Photo Credit:

Pradeep Gaur

Vimlendu Jha, head of Delhi-based environment non-profit Swechha India, says, “When those who have greater equity and agency move out, there are even fewer people to raise their voice for clean air. This affects those who are poorest and live through far worse conditions.” Residents need to ask their elected representatives about clean air. “Even though air pollution is a political-party-agnostic issue, it is a political issue,” he says. It was evident in the Delhi Police’s forceful response to peaceful protests by citizens last month.

Students in masks at the Kartavya Path amid dense smog near the India Gate in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

–

Protest against Delhi’s hazardous air pollution.

| Photo Credit:

Bilal Kuchay/NurPhoto

Residents protest against rising air pollution in Delhi NCR.

| Photo Credit:

Sathiya

People protesting against air pollution near India Gate, in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Sushil Kumar Verma

A protester being detained by security personnel during a protest against worsening air quality in the national capital, near India Gate.

| Photo Credit:

Karma Bhutia

Police personnel detain a protestor during a protest against Delhi air pollution.

| Photo Credit:

Karma Bhutia

As of 2025, there have been at least five PILs (public interest litigations) and, or, writ proceedings filed before the Supreme Court and the Delhi High Court with respect to air, according to Justin Bharucha, advocate and managing partner at Bharucha & Partners, Mumbai. “This follows from the position that clean air is a fundamental right as per Indian law and enforcing that right must necessarily be through Indian courts,” he says.

Prabhakaran says, “In our study on impact of air pollution across 10 cities in India we found that cities like Bengaluru, Shimla or Varanasi with lower levels of pollution of 15-40µg/m3 also showed increased risk of mortality.”

Leaving Delhi is neither practical nor possible for most residents. As Roychowdhury quips, “Wherever you run to, those cities are also polluted. Most air pollution-related illnesses and health effects occur at much lower levels of pollution. It is not a linear effect.” Leaving Delhi is neither practical nor possible for most residents.

For nine-year-old Aatrey S. Menon, whose family moved to Chennai in 2023, Delhi will remain home, a place he’d love to return to. Leaving his birth city meant saying goodbye to half his childhood. “I miss everything about Delhi — the weather, my friends and even the cold,” he says.

He loved wearing sweaters in winters, misses his favourite pizza place and toy store, and even the air pollution — which meant he could stay at home and skip homework.

(With inputs from Tanushree Ghosh)

The Ahmedabad-based independent journalist previously lived in Delhi NCR.