As the beacon of political freedom in modern India, the Indian Constitution has held out the promise of secular liberal values for all its citizens. In turn, this vision has animated a constitutional aspiration to define the Indian people as a community of individual citizens, free from the parochial divisions that historically plagued the constitutional horizon of the preceding colonial state. However, drawing on my recently published book ‘India’s Communal Constitution: Law, Religion and the Making of a People’, I will try to demonstrate in this essay a long-standing and less examined tendency that stands alongside the Constitution’s liberal promise, but which identifies the Indian people in religious and communal terms. This inherent inclination, subtly yet powerfully, shapes how we, the people of India, are understood and drawn into constitutional practice.

As a counter-intuitive argument that goes against the grain of conventional wisdom, I make my case by drawing on the making of political identity in modern India, as it has influenced aspects of our constitutional common sense. Thus, I begin with the suggestion that the Constitution, as well as its practice, does not only disclose a monolithic liberal project, but is instead a field of contestation. Here, the aspiration of individual citizenship is presented against a powerful antagonist: the inclination to view Indians as embodiments of religious communities. This is not merely a powerful social force, like the rise of Hindu nationalism, influencing from the outside, as it were, the workings of constitutional institutions. Instead, the communal Constitution points to a structural orientation internal to the Constitution’s design and practice, deeply embedded amidst its liberal commitments. To all those who value these liberal commitments, the communal constitution might even be termed a “pathological expression of constituent power”, where the sovereign authority of the Indian ‘people’ is articulated in national, communal, and parochial terms, rather than solely as a collective of free and equal citizens.

In making salient a communal constitution for this essay, I draw upon my work and limit inquiry to religion, though there could be other Indian social identities, such as caste, language, tribe and so on, that could also be mobilised to portray the Indian people as embodiments of these identities. However, given its profound impact on Indian constitutional history, most notably evidenced by the partition of British India, I focus on religion as it has been constitutionally drawn upon to shape the political identity of the Indian people. To trace the imprint of religious identities on contemporary India’s Constitution, I draw on three historical processes or axes – toleration, social reform, and constitutional representation, through which the colonial state drew on religion to structure political identity. Having traced this form in which the colonial state organised religious or communal identities, I then demonstrate its lasting influence across various domains of Indian constitutional law: religious freedom, personal law, minority rights, and the identification of caste groups.

Drawing on the turn of history and historical studies, I think it is instructive to go over what I call a template of communalisation – comprising, toleration, social reform and constitutional representation – as they took shape in the colonial state.

Firstly, colonial toleration became a peculiar instrument of communally demarcating the Indian people. While seemingly benign, the British policy of tolerating diverse Indian religious practices, particularly through Governor General Warren Hastings’s Judicial Plan of 1772, mandated governing Hindus and Muslims according to their ‘respective religious laws…’. This commitment to toleration wasn’t simply pragmatic; it necessitated a pervasive colonial search for what I call the true and axiomatically applicable foundations of Indian religious traditions. As the example of legal strategies relating to Sati demonstrates, the colonial state sought to distinguish practices true to religious doctrine or axioms from those that were not, often tying these true doctrines to the religious tradition of a people. This truth-seeking approach inadvertently sharpened communal identities by reducing the vast swathes of local practice to clearly defined doctrinal truths, thereby producing sharply defined conceptions of religion and a society divided into religious communities or peoples.

Secondly, this foundational understanding of distinct religious communities informed the movement for social reform. As colonial officials grew more confident, they began reforming ethically and morally deficient aspects of Indian religious practices. Even the abolition of Sati in 1829, while seemingly progressive, was argued on grounds of religious truth — that Sati had no foundation in the religious canons and doctrines of the ‘Hindu’ people. This process gradually empowered Indian nationalists, who, drawing on these colonially styled accounts of Hindu and Muslim identities, took over the reform agenda. Reform thus became the communally organised ground where elites spoke on behalf of fellow Indians by reinforcing their identities as Hindu and Muslim people. Social reform thus reiterated and solidified religious identities as axes of social solidarity and political identification.

Thirdly, the British introduced constitutional reform through political representation for communal identities that their rule had solidified. Political representation for Indians, particularly through communally organised separate electorates, became the most obvious manifestation of this communal constitutional imagination. Statutes like the Indian Councils Act of 1909, the Government of India Act of 1919, and the Government of India Act of 1935, while bringing Indians into government, reified social identities and sharpened the fault lines of social division. These statutes, driven by the perception of India as a “congeries of widely separated classes, races and communities”, implicitly fostered a constitutional identity where religious communities, most notably Muslims, were recognised as ‘minorities’. This communal shadow of viewing India as a collection of distinct and divided communities continued to exert a significant influence on the design and practice of independent India’s Constitution, despite the aspiration of the new nation-state to move past this colonial logic.

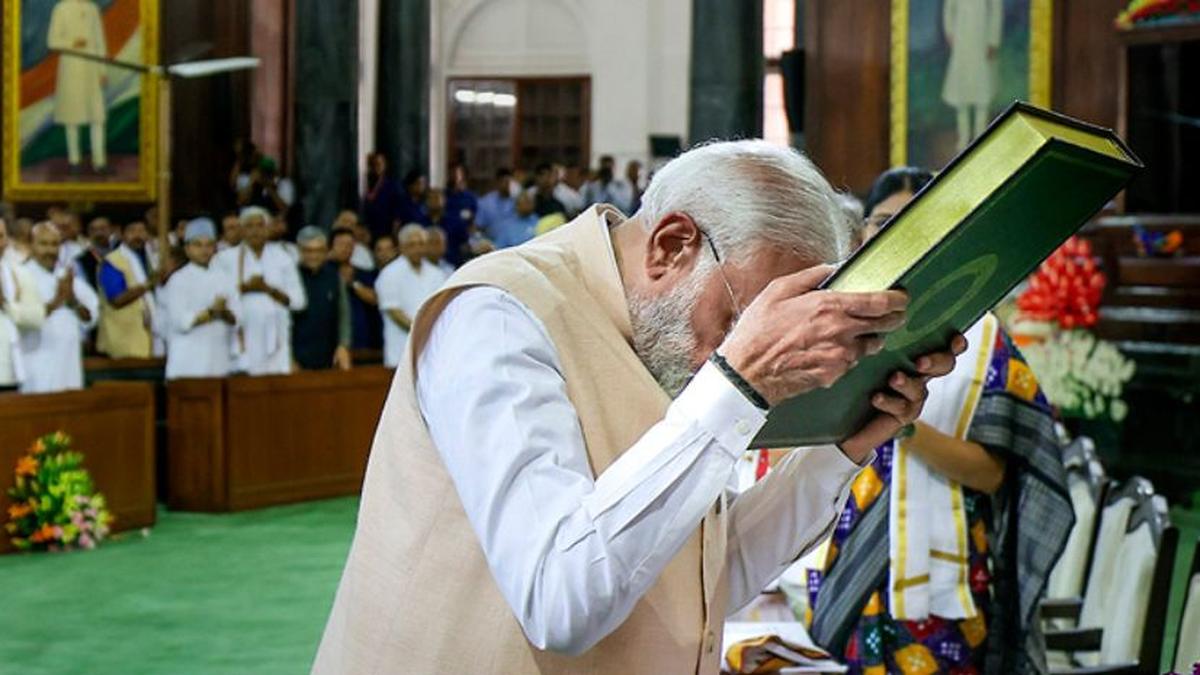

Jawaharlal Nehru arriving at a meeting of the Constituent Assembly in the Council Assembly in the Council House Library, New Delhi, to attend the discussion on the Constitution.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Despite the overwhelmingly liberal and secular design of the independent Indian Constitution, the historical weight of communal identities, as I have just outlined them, has seeped into the constitutional imagination of the Indian people. Let me illustrate this imprint across key areas:

Essential practices test

The Indian Constitution’s provisions on religious freedom (Articles 25-28) appear, on the surface, to be standard liberal guarantees. However, the institutional practice of these provisions, particularly through the Supreme Court’s ‘essential practices test’, has functioned to foreground communal identities. This test, as articulated in the Shirur Mutt case (1954), initially suggested that ‘what constitutes the essential part of a religion is primarily to be ascertained with reference to the doctrines of that religion itself’. Yet, Justice Gajendragadkar’s subsequent decisions in the 1960s fundamentally transformed this test, shifting the authority from a community’s subjective understanding to what a court judged to be essential to that tradition. This interpretative move allowed courts to act almost as theologians, sifting between different kinds of religious claims, establishing some while denying others. For instance, courts have ruled on whether cow sacrifice is essential to Islam or if a particular dance is central to the Anand Margi community.

While legal scholars often critique this judicial hermeneutics for sitting uneasily with India’s secular constitutional state, I would like to suggest that this ‘error’ serves as a crucial diagnostic. It reveals a deep-seated inclination to identify religion through its ‘essential truths’, a conceptual frame that holds together a communal account of India, its people, and the problem of establishing government for its diverse peoples. By defining religious freedom this way, the essential practices test has emphasised religious communities and the differences between them as the fault lines that have defined the identities of the Indian people.

In fact, the Ram Janmabhoomi–Babri Masjid dispute (Ayodhya case) stands as a stark example of this account of the Indian people. What began in colonial courts as a property dispute over a shared religious space was gradually transformed into a conflict pertaining to the Indian people, understood as divided by ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ identities. Colonial judges, in their pronouncements, explicitly cast the disputed structure as an emblem of a people divided. Even the Supreme Court’s 2019 judgment, while attempting to steer clear of explicit religious essentialism in its main reasoning, notably included an unusual addendum that slides back into casting the dispute as one requiring the resolution of the question whether ‘the disputed structure is the holy birthplace of Lord Rama as per the faith, trust and belief of Hindus’. This deployment of essential Hindu truth in the addendum, I argue, has continued a long tradition of state practice that identifies religion and religious freedom with the truths of a people. The Ayodhya case, therefore, illustrates how the essential practices test, when applied broadly, can inflect Indian constitutional identity as the embodiment of one or another community.

India’s personal laws

The working of India’s personal laws provides my second illustration of how the Indian people are constitutionally characterised in communal terms. These laws, which govern family relations based on religious affiliation (e.g., Hindu Law, Muslim Law), have historical roots in colonial toleration and the project of ‘legal recovery’ that reduced diverse local practices to axiomatically applicable propositions identified as essential doctrines of distinct peoples. In this respect, the colonial state presumed nationally organised religious communities (like Hindus, Muslims, and so on) and sought uniformity and certainty in applying the texts like the dharma sastras, fundamentally altering the plural and adaptable nature of these texts. When thinking about the development of personal law in relation to the Hindu tradition, it is useful to draw on contrarian positions like that of the colonial judge James Henry Nelson, who argued that Anglo-Hindu law misapplied dharma sastra rules to groups who had little to do with it. In its stead, he emphasised the primacy of diverse local customs. Nelson provocatively questioned “whether such a thing as Hindu Law… existed in the world” and asserted that “there is not, and … never has been, a Hindu nation or people”. Yet, his arguments were largely rejected, affirming the colonial axiom of India as a collection of people best understood as divided by doctrinal and axiomatically applicable truths ascertained and administered by the British state. This meant personal laws became, among other things, a legal framework that identified Indians as distinct groups of people.

At Independence, the question of personal laws was addressed in Article 44, a directive principle urging the state to work towards a uniform civil code. This was a compromise: personal laws would continue, but the state aspired to eventually supersede them in its aspiration for a liberal secular or perhaps even national constitutional culture. Those arguing for personal laws, primarily Muslim members of the Constituent Assembly, linked them directly to religious freedom and the way of life of Muslims understood as a people. However, proponents of a uniform civil code, like K.M. Munshi, argued for national unity and the state’s sovereign power to enact secular legislation over matters previously deemed religious.

The Narasu Appa Mali case (1952) was pivotal in cementing the communal character of personal law in Independent India. In this case, the Bombay High Court had to decide on the constitutionality of a law banning bigamous Hindu marriages. While upholding the state’s power to reform religious practices, the court made a significant, and doubly puzzling, pronouncement: personal laws, unlike other laws, do not derive their validity on the ground that they have been passed or made by a Legislature or other competent authority but from their respective scriptural texts. This meant that personal laws were deemed sui generis (unique) and, crucially, immune from fundamental rights scrutiny. This decision, which has not been reversed, paradoxically recognises and foregrounds the communal conceptualisation of the Indian people on which the colonial state originally founded personal laws – that is, as a people founded on and divided by religious doctrine.

Even recent judgments like Shayara Bano (2017) on triple talaq, while declaring the practice unconstitutional, still saw some judges reiterating that personal laws are protected by Article 25 and thus immune from fundamental rights review, demonstrating the persistence of the Narasu legacy. Furthermore, it’s also useful to notice what I call a ‘jurisprudence of exasperation’ in Supreme Court decisions (e.g., Shah Bano, Sarla Mudgal) concerning the uniform civil code. While ostensibly pushing for national unity, these judgments often make gratuitous remarks on the loyalty of Muslims as citizens and single out Muslim personal law, thereby amplifying the representation of the Indian people as constituted and divided by religious identity. This reinforces a political sociology that casts India and Indians as boxed into and divided by communal identities.

A lurking majoritarianism

The reorganisation of minority rights in Independent India was intended to foster national unity and equal citizenship, moving away from the colonial system of communal representation. Articles 29 and 30 grant rights to religious and linguistic minorities to protect their traditions and establish educational institutions. While B.R. Ambedkar envisioned a broader, inclusive understanding of ‘minority’ beyond the political safeguards granted to minorities in colonial India, adjudicatory practice has carved out Article 30 as granting special rights to a very narrow understanding of the term, leading to a scramble by different groups to present themselves as minorities.

In this practice of minority rights, the identification of minorities (especially religious minorities) often implicitly relies on a nationally, axiomatically, and doctrinally organised Hindu majority. This conceptual framework sees religious minorities as identity groups distinct from what was presumably a doctrinally demarcated and national majority of Hindus. The Ramakrishna Mission and Swaminarayan cases exemplify this approach to minority rights. These groups, despite their unique self-presentations and claims of distinctness consistent with India’s plural traditions, were deemed by the Supreme Court to be part of the broader, doctrinally defined ‘Hindu community.’ The courts, in these instances, chose to drape an overarching axiomatic and doctrinal frame on Hindu belief and practice to subsume these diverse traditions within a singular, unified Hindu identity. This effectively incorporated and absorbed the plural perspective about Indian society as a superstitious accretion over ‘Hindu identity and doctrine’.

Similarly, in the Bal Patil case (concerning Jain claims for minority status), the court, when confronted with the challenge of locating Jains in relation to a doctrinally understood conception of the Hindu community, ultimately resisted declaring Jains a minority (though they later succeeded through government action). Notably, Justice Dharmadhikari argued against recognising minorities in ways that encouraged ‘minority sentiment’, which would fragment the conceptualisation of a Hindu political community on which constitutional identity in India was built. This reveals how a doctrinally and axiomatically conceived Hindu community has fed into a national and potentially majoritarian identity against which minority identity has acquired salience and recognition. Even when court decisions like in TMA Pai allowed for a different and State-level determination of minorities, the underlying majoritarian frame often remained, simply shifting the scale of identification rather than fundamentally altering the communal lens.

Sacralising caste

The constitutional scheme to address caste injustice and the disabilities of the Scheduled Castes (formerly Depressed Classes) also reveals a deeply communal characterisation of the Indian people. While the Constitution aimed for transformative social reform and equality (e.g., Articles 14 and 17 abolishing untouchability), the problem of caste was largely framed as a ‘Hindu problem’.

The historical debates leading to the Poona Pact (1932) illustrate this. While Ambedkar sought to address the systemic discrimination faced by untouchables as a broader political problem for the entire polity, Mahatma Gandhi viewed it as a ‘malignant and unjust accretion on Hindu society’ to be removed through reforms. This ‘Hindu’ framing, despite Ambedkar’s efforts, continued to persist in the Constitution as well.

The identification of Scheduled Castes within the Constitution, particularly through the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, explicitly states that ‘no person professing a religion different from Hinduism shall be deemed to be a member of the Scheduled Castes’. This, I argue, betrays a sacralized and communal account of caste. Drawing on Marc Galanter’s framework, my work shows how caste came to be primarily understood through a sacral frame – as constituent parts of a unified Hindu religious order, held together by axiomatically applied scriptural doctrines, despite the existence of ‘sectarian and associational’ understandings of caste that included non-Hindu groups.

Judicial decisions reinforce this sacralization. In S. Rajagopal v. C. M. Armugam (1969), the Supreme Court ruled that a Scheduled Caste individual lost their caste status upon converting to Christianity because they understood Christianity to be a religion that does not recognise any caste classifications. This and other similar judgments cemented the idea that conversion is a sacral act that detaches individuals from preceding social relations. Even in Soosai v. Union of India (1985), while the court considered the possibility that caste disability could survive conversion, it still operated under the presumption that Christian doctrine effaced caste, requiring concrete evidence to rebut the presumption of this ‘sacral model’. The legal doctrine of eclipse, seen in cases like K.P. Manu (2015), further solidifies this, holding that caste remains under ‘eclipse’ upon conversion and automatically revives upon reconversion to the Hindu community. This is a clear instance where caste inequity ensuing from sectarian and associational social forms is pushed aside to firmly establish a sacral Hindu model of caste in Indian constitutional practice.

Furthermore, the identification of ‘Backward Classes’ for affirmative action (Articles 15(4), 15(5), 16(4)) also aligns with this sacralized understanding of caste. Despite attempts to include other criteria for backwardness (like income or education), a sacral account of caste has remained the most significant social marker of backwardness. For example, in the landmark M.R. Balaji v. State of Mysore (1963) case, the court, while not allowing caste to be the sole determinant, nevertheless asserted that caste was a sacral bond that excluded non-Hindu communities. The Indra Sawhney judgment (1992), concerning the Mandal Commission recommendations, further underscored this, with Justice Jeevan Reddy articulating caste as intrinsically linked to the Hindu religion, painting a sacral account of Indian society as the stark reality. Thus, even when addressing broader social backwardness, the background assumption of caste as a sacralized and axiomatically organised Hindu phenomenon prevails.

A layered understanding

Thus, to round up, I have tried to present a communal dimension in Indian constitutional imagination and practice as a descriptive, diagnostic, and explanatory lens aimed at bringing conceptual clarity to understanding alternative forms of representing the Indian people. In doing so, my analytical and descriptive canvas has tried to cast the constitutionally dominant liberal bid to fashion the Indian people as a community of individual citizens as one among other ways of conceptualising the Indian people. In particular, I have shown that the liberal people cohabit with, and are constantly challenged by, the deeply entrenched ‘communal-nationalist’ representation of India as a fragmented political community founded on religious groups divided by their essential and axiomatic scriptural truths. This nationalist assertion often identifies the national mainstream as Hindu, set against various minorities, primarily Muslims.

Even as the essay foregrounds the communal-national vision, in drawing it to a conclusion, it’s also important to touch upon less prominent conceptual axes of the people (as identified by much scholarship), such as the ‘plural’ and ‘regional’ accounts of the Indian people. Arguments from plurality, for instance, challenge the dominance of communally, nationally, axiomatically, and doctrinally demarcated forms of identifying minorities and castes. These arguments, reflecting a bottom-up and sociologically driven form of political identification, often find little space in mainstream constitutional discourse. They offer an alternative lens, perhaps akin to Gandhi’s vision of civilizational plurality, which sought to embrace India’s diverse social practices rather than homogenise them into singular, nationalised religious identities. Which of these perspectives on the people is most appropriate to mould the future of Indian constitutional democracy is a question that I have almost entirely set aside in this essay, with the exception of pointing to the dangers presented by the communal-national conception of the people. That is, the insider-outsider, friend-enemy, us-them logic that is overtly part of this way of arguing for Indian constitutional identity.

Collectively, this contested constitutional field that I have tried to foreground brings to view the ecology of political projects that have sought to mould, articulate and defend Indian constitutional identity. Without this deeper understanding, I have implicitly suggested all along in this essay that we risk overlooking the subtle yet powerful ways in which our constitutional framework continues to define us, not merely as citizens, but as members of demarcated religious communities.

Mathew John is a Professor at the School of Law, BML Munjal University in Delhi, India.