What remains barely out of one’s grasp is more eye-catching than what is in hand. Here is a “classic” flavour to this universal truth. Ranjit Pratap holds a coveted finisher’s plaque from the Classic Himalayan Drive 2025, but would not have any more of it.

Do not get this wrong. This is not the existential emptiness that sometimes shadows achievement; not the bottomless pit of despondency lying right below the summit. Ever since the plaque made it to the gallery wall at his home in Chennai, Ranjit has grown a couple of feet taller, and there is an evident spring to his step. He defines the experience of rolling through the Himalayas as fulfilling and Team Firefox’s conduct of the event (November 1-10) as impeccable, particularly the massive resources ploughed in to cushion the edges. And in this state of elation, Ranjit has taken a calculated decision not to reprise the effort that begot him this enriching experience and recognition. Because “it is too tough on the system”.

During the Classic Himalayan Drive 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Ranjit (CMD of Rayala Corporation and founder of Historical Cars Association of India) is referring not entirely to his body and mind, but to the wheels that carried him through this ten-day adventure. He headed into the Drive with a 1977 Peugeot 504 (diesel). That is par from the course. The Classic Himalayan Drive, which has five editions to its name, is designed exclusively for classic and neo-classic cars with their birth years ranging from 1958 to 2002.

The route for this edition was Noida-Ramnagar-Corbett National Park-Rishikesh-Theog- Jalori Pass-Rohtang Pass via Atal Tunnel and Koksar-Manali-Chandigarh.

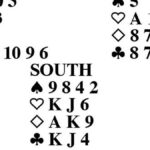

The finisher plaque from the Classic Himalayan Drive given to Ranjit Pratap and Uma Ranjit.

| Photo Credit:

PRINCE FREDERICK

The Classic Himalayan Drive runs on nostalgia the route seeking to recreate the ones followed by the iconic Himalayan rally of the 1980s, but removing the ragged edges. But the drive happens in a real estate of a kind where danger can be minimised, not wiped off the map. The drive is non-competitive and every finisher is a winner. However, participants compete against steep inclines, hairpin bends, roads washed by rains, and narrow roads caressing boulders. And ironically, they are pitted against their own machines, particularly those at the wheels of older classics.

During the Classic Himalayan Drive.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Ranjit’s driveway resembles a shopping complex’s parking lot boasting a wide collection of classic cars. On the face of it, he had a job on his hands deciding on the machine that would go with him and his wife Uma Ranjit (as navigator) to the Himalayas. In the end, the four-speed, 2.3-litre (diesel) 1977 Peugeot 504 seemed like a great choice.

He did not have second thoughts about the decision until Day 7 of the Drive when he found himself staring up at the Jalori Pass, with the braking capacity of his car reduced to 20%. At that point, he had a wistful longing for his 2000 Prado, which was well within the 1958-2002 cut-off.

A “group picture” of vehicles that took part in the Classic Himalayan Drive 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

A majority of the participants — particularly those from other shores including the United Kingdom, France, Kenya, Malaysia and Singapore — had gone in for younger classics better suited for the unhelpful conditions. There was also a clutch of contemporary four-wheel drives as an add-on. The Indian contingent included half-a-dozen older classics, out of which only two (Ranjit’s 1977 Peugeot 504 and Kolkata-based Prithivi Raj Tagore’s 1959 Mercedes-Benz 180 Ponton) made it to the finish.

In its time, Peugeot 504 was hailed as an all-season car. Post-Himalayan Drive, when this writer saw this darker-beige-coloured car smugly lazing about in Ranjit’s driveway, ready for a photoshoot, he knew why straightaway. With a linear-look, far from bulbous and strung tightly together, somewhat Chippiparai-like — or whippet-like, for western sensibilities — this machine would have made winsome first impressions at dates and board meetings. According to collective automotive memory, it had the staying power to be a reliable ally in field work. “All over Africa, the Peugeot 504 was used as an everyday vehicle as it could withstand bad roads. Peugeot had an assembly facility in Kenya,” remarks Ranjit. The pickup version of the Peugeot 504 was said to be a trusty ”farmhand”.

However, on the Drive, the limitations of his Peugeot 504 could not be swept under the snow. It was still a rear-wheel-drive machine thrust into a business better left to four-wheel drives. Ranjit explains: “Being a rear wheel drive, this car has an edge over front-wheel drives on slightly challenging inclines. But it could easily meet its Waterloo in roads that are snow-washed; even the introduction of an aftermarket limited slip differential would not improve its performance significantly in such an environment.”

Ranjit recalls that at Jalori Pass, he tackled a scary incline that lasted seven kilometres by reducing his option to just the first gear, keeping the engine humming, careful enough not to slave-drive it lest it fumed at him, overheating and squatting down in an act of non-cooperation. And the slope on the decline was scarier still, as the car was braking at 20% percent of its braking capacity due to a failed brake booster.

On the hair-raising drive up and down Jalori Pass, Ranjit had a taste of the “hedge” around the nearly 40 participants put in by Team Firefox — “six Deputy Clerks of the Course with of course, the Clerk of the Course, Sudev Brar; two sweeps, one of them being Brar himself; and a full-fledged team of mechanics and a good number of recovery flatbeds and ambulances”.

Ranjit elaborates: “Every day, we had to cover between 200 to 250 kilometres, and overall, we had clocked around 2,000 kilometres; looking back, it seems like a miracle that we made it across this distance and survived treacherous road conditions, including a lot of washed-out patches and those hit by past landslides. It was possible because of Rajan Syal’s team taking care of the minutest details, not to mention the 1980s nostalgia that egged us on.”

Published – November 20, 2025 01:01 pm IST