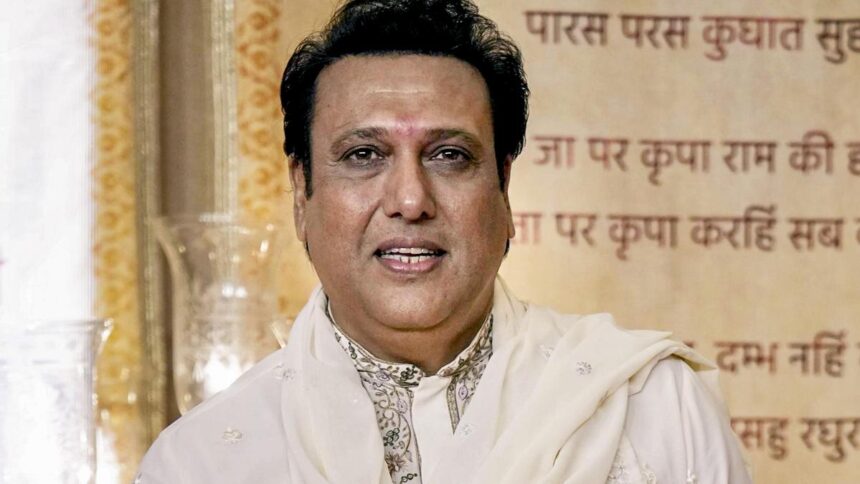

A Japanese sparrowhawk sighted and photographed by Madras Naturalists Society member Ramanan R.V. at Adyar Estuary on November 7, 2025.

| Photo Credit: Ramanan R.V.

Touch upon this topic about the Adyar Estuary, and one ends up in an ouroboric, cyclical reasoning. The conclusion takes one to the starting point which feeds back into the same conclusion. It is a chicken-and-egg conundrum in a birding contest.

The ODI strike rate Abishek Sharma currently enjoys among batters, the Adyar Estuary enjoys among birding patches in and around Chennai in terms of hyperticks (sightings of unexpected feathers). Every birder worth their pair of binoculars would have clocked in numerous hours at the Adyar Estuary. And that begets the conundrumical question: do birders flock to the Adyar Esturay in large numbers because it throws up avian surprises regularly or does the Adyar Estuary amass surprises because birders flock to it in large numbers?

A Japanese sparrowhawk sighted and photographed by Madras Naturalists Society member Ramanan R.V. at Adyar Estuary on November 7, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Ramanan R.V.

Forget its overall rare bird stats. Over the last couple of months, the Adyar Estuary has hosted the Saunders tern, and then organised a high tea with a female red-headed bunting; and in the week that went by, it had a dalliance with a Japanese sparrowhawk.

No mistyping there; a Japanese sparrowhawk indeed. The lucky pair of eyes that peered through the binoculars belongs to Ramanan R.V., a Madras Naturalists Society (MNS) member and a birder.

The encounter with the Accipiter hawk happened in the liminal zone at the Adyar Estuary where one breathes in the same air that caresses the broken bridge and the peripheral park of the compound wall enclosing the Theosophical Society campus. This part of the Estuary can be christened “unexpected birds check-in counter”, given the enviable aggregate of such sightings it boasts.

Ramanan shares the details of the encounter with The Hindu Downtown: “On the morning of November 7, around 6.30 a.m., there was a commotion inside the TS campus. Drongos were shouting, chasing some bird and then all of a sudden this bird came out and it started chasing a green bee eater. It went on two sorties trying to catch the green bee eater, but was unsuccessful in the attempt. Initially I was looking through the binoculars and I thought it was the usual Shikra. Then I noticed it was on the leaner side and slightly smaller than a Shikra. I then took my camera and captured a few shots of the raptor.”

He would return to the spot the next two days, but the bird did not show up.

Ramanan notes that photos of the bird were “subsequently shared with the internal raptor interest group of the Madras Naturalists’ Society (MNS) for assistance with identification. The initial impression, given the location, was that of a Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus). However, a detailed analysis of the photographs by the group confirmed the bird’s identity as an immature Japanese sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza gularis).” Both are members of the family accipitridae.

Ramanan remarks that the photographs came under the knitted brows of Gnanaskandan Kesavabharathi and Nirav Bhatt, luminaries on raptors.

The Japanese sparrowhawk shuttles between its breeding home in East Asia, which inludes China, Japan, Korea and Siberia and its wintering home in South-east Asia.

Ramanan elaborates, “Within the Indian subcontinent, its occurrence has been documented as a migrant and winter visitor primarily, if not exclusively, in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. This is the first photographic sight record of the species from mainland India. There are records from Walong and Namdapha in Arunachal Pradesh. Without documentation, these records are just claims. This is the first time we are documenting the sighting of a Japanese sparrowhawk in mainland India and then showing it.”

Identification pointers

Here are selective points from the observations MNS member and raptor expert Gnanaskanan Kesavabharathi made based on the photos of the Japanese sparrowhawk Ramanan R.V. shared with him. These are identification pointers that rule out “lookalikes”.

Pointer one: “Lack of black-tipped outer primaries eliminates Chinese sparrowhawk.”

Pointer two: “Based on the number of black-barring in the primaries (especially P8) and the number of primary fingers, we can eliminate Eurasian sparrowhawk. Also mesial stripe was not visible in all image angles. In initial review, I could not count primaries right with available images and mistook the gap in outer primary as missing primary. Eurasian sparrowhawk in all ages have good protruding P5 finger.”

Pointer three: “Based on the indistinct mesial stripe, the number of bands in P8 (less than six in Besra) and considering they are residents with not much of movements recorded, we can eliminate Besra as well.”

Building up the the identification profile with these pointers, Gnanaskandan Kesavabharathi concludes: “Leaving us the best contender as Japanese sparrowhawk, for which all these elimination pointers fit in.”

Published – November 13, 2025 10:52 am IST