There are two ways we get to see — and know — a city: by setting foot in it, and through cinema. In the case of cinema too, there are two ways to become familiar with a place: through commercial movies and through realistic portrayals. As far as realistic portrayal is concerned, there are three well-known ways of looking at the city of Kolkata: through the eyes of Satyajit Ray, of Mrinal Sen and of Ritwik Ghatak, the holy trinity of Indian parallel cinema.

They shot their films in Kolkata — Calcutta back then — during the same time when, unlike other cities that were beginning to kindle dreams, Calcutta, having long reached the pinnacle of glory, was on the decline. But even then, the depictions were different. For Ray, Kolkata was more of a socio-political entity on whose vast surface humanity played out its part. For Sen, it was the ‘El Dorado’ — the magical, mystical city he adored.

Ghatak’s portrayal, however, was unique. To him, the city itself was also a character, giving refuge to the displaced. A place, itself devoid of emotions, like a strict, non-demonstrative father or teacher, seemingly unsympathetic and uncaring, but which had hidden humane nerves.

City on the move

Ghatak’s 1958 film Bari Theke Paliye opens with a mischievous boy, who has a dislike for his strict father, running away to Calcutta, which he calls “El Dorado”, “where night is as bright as the day”. The city is introduced with the sun rising over the Howrah Bridge. That’s exactly how Kolkata is introduced to hundreds of new arrivals every morning even today. Not exactly a city of opportunities or dreams, but still a city where many run away carrying hope, or for survival.

If you discount the absence of trams (almost extinct now) and if you ignore the phones in people’s hands, one could still be in 1958: the bridge occupied with people at the crack of dawn; workers carrying loads on their heads, their movement somewhere between a walk and a jog; men pushing carts laden with a mountain of sacks. Every labourer looks — and is — busier than a doctor or a CEO: they have no time to lose; Kolkata moves because they move.

If Howrah Bridge depicts arrival, search for opportunities happens in places with tall buildings. Much of those places stand even today, so much so that if Ghatak were to return with his camera, he wouldn’t find much missing except the trams and perhaps phone booths and hungry people on the streets.

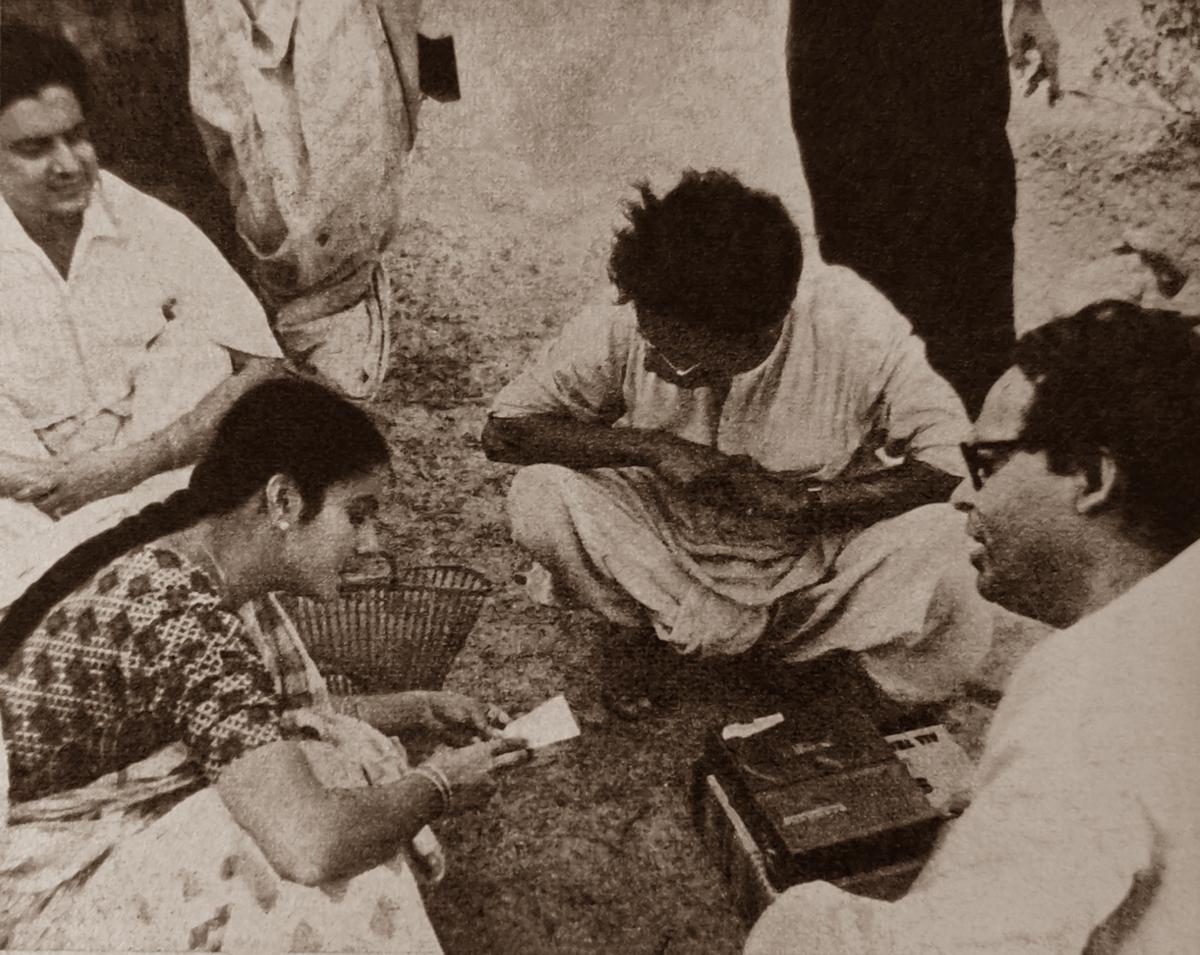

Actor Madhabi Mukherjee (far left) with director Ghatak (extreme right) on the sets of ‘Subarnarekha’.

High-ceilinged office buildings with broad staircases and large windows; a parallel ecosystem thriving on the pavements right outside — barbers, food vendors, stationery sellers; and on the wide roads a stream of humanity, each with a story that could be another Meghe Dhaka Tara or Subarnarekha. Since Kolkata takes pride in being a once-upon-a-time city, it is unlikely those watching Ghatak’s films, for at least another few decades, will find much of a difference between then and now.

Meeting of two migrants

Yet, a lot of water has flown under the Howrah Bridge since his time. Ghatak dwelt on the subject of Bengal’s partition, dedicating a trilogy to it in the first half of the 1960s. But those refugee colonies his stories were set in are today a thing of the past: they have evolved into neighbourhoods that belong to the City of Joy. In any case, unlike in Punjab, the refugee movement was not a one-time event in Bengal: people migrated over decades, the final massive exodus taking place in the early 1970s. Memories of bad days, therefore, are not confined to 1947 alone.

One of the organisations to first hold an event this year to mark Ghatak’s centenary was the West Bengal Hindi Speakers’ Society, which had a screening of Subarnarekha, the third in the filmmaker’s Partition trilogy, as long back as on June 8. Ashok Singh, general secretary of the society, who is a former head of the Hindi department at Surendranath Evening College, had said at the time, “He is my most favourite filmmaker. If you see Ray’s films or Mrinal Sen’s films, you will find Hindi-speaking people shown as either drivers or doormen. Whereas if you watch Ghatak’s Bari Theke Paliye, you will see a boy running away from his village to the big city of Calcutta being shown kindness by a Hindi-speaking man on the road selling sattu. Such a humane portrayal of the meeting of two migrants!”

Every city is a city of migrants. Ritwik Ghatak, perhaps the only one to dwell on the subject, showed that even Kolkata is one.

bishwanath.ghosh@thehindu.co.in

Published – October 31, 2025 06:10 am IST