In 1947, Indians won their freedom from two centuries of colonial rule through one of the largest mass movements in history. The effect was felt across the British Empire, which depended on the army, labour, and capital that India provided. In international fora, India assumed a role as the leading spokesperson for anti-imperial causes.2 India’s Independence proved to be one of the most significant events in the decades-long unfolding of decolonisation. Yet, hardly anyone belonging to the Indian National Congress — the party that led the anti-colonial struggle — or the scholars and scribes who wrote about it, used the word ‘revolution’ to describe what they did or saw. The word that has come to stand in for an epochal shift in the life of a polity is conspicuous in its absence from the historical consciousness of Indians. Perhaps the most paradigmatic case of 20th-century decolonisation left behind no ‘memory’ or ‘spirit’ of the revolution.

However, the members of the Constituent Assembly frequently spoke of revolutions. Revolutions are rarely far from anyone’s mind when constitutions are made. In deliberations of a Constituent Assembly, one expects it to appear as an event of the past, which has brought about the conditions for the making of the new constitution. In Delhi, they were not talking about what happened in the past. Every time one of the Assembly members spoke of revolution(s), the reference was to an uncertain and troublingly near future. The Indian Constitution-makers found themselves not at the end but on the “eve of revolutionary changes”.3

The Independence movement was the result of a contingent and fragile alliance between the urban elites and the largely peasant masses. The contingency was their shared unfreedom under colonial rule. The fragility was the outcome of the fact that the departure of the British did not in itself change the unequal, hierarchical, and exploitative social conditions in which the vast majority of Indians lived. Even if directed against an alien enemy, mass mobilisations have an inherent tendency towards radicalisation. The militant energy of the masses had fuelled Congress’s ability to credibly challenge the colonial state. At the same time, popular political expressions were frequently directed against Indian elites who exploited their putative fellow travellers on the nationalist journey. As a result, the anti-colonial struggle generated multiple insurgent images of freedom, which the Congress could hope to harness but never fully control. Over the last decade of colonial rule, the Congress began to transform itself from a party of mass mobilisation to a party of government. The success of the mass mobilisation made a postcolonial government an inevitability, while that same mobilisation generated unease in the minds of the governors-in-waiting. So the Congress accepted a transfer of power in an orderly fashion under the immaculate legality of the British Parliament, betraying several of their stated principles. Consequently, it inherited in near-pristine conditions the formidable apparatus of the colonial state, with its administrators and its army. “Through a fortunate or unfortunate chance, it turned out that it was not through a bloody revolution that we have worked out our emancipation,” the then Congress president, Pattabhi Sitaramayya, said in the Constituent Assembly.4 There was no revolution in India — at least not yet. On that “not yet” hinged the entire project of postcolonial constitution making.

While there might have been no revolution to end, there was one that needed to be prevented. Absent from the anti-colonial past, the revolution demanded a place in the postcolonial future. From where the Constitution-makers stood, this future ‘revolution’ had two possible incarnations. It could take the shape of a violent uprising of the disaffected masses, fueled by inequality, exploitation, and unfulfilled aspirations of freedom, causing “insurrections and bloodshed”.5 Alternatively, it could be a thoroughgoing transformation of the socio-economic conditions, carefully planned and managed. Their challenge was authoring a revolution of the second kind, to avoid a revolution of the first kind authored in the streets. The nascent postcolonial present, Jawaharlal Nehru told his colleagues in the Constituent Assembly, was “something which is dynamic, moving, changing and revolutionary.” “[I]f law and Parliament do not fit themselves into the changing picture they cannot control the situation completely.”6 Rather than extralegal insurrections, revolution had to mean large-scale yet orderly change — “A peaceful transference of society”, as Purnima Banerji defined it in the Assembly.7 The spectre of insurrection caused anxiety; planned transformation was the aspiration. It had to be a revolution without a revolution. And the Constitution had to be its institutional architecture.

Constitutions are, by and large, analysed by lawyers, for lawyers. Lawyers are specially ordained to be the custodians of the sacred text for our secular times. They are trained to find internal coherence amongst texts, and subject their particularities to ‘timeless’ legal categories and precedents. This is how we get an appearance of certainty, stability, and permanence of meaning, on which the rule of law, and indeed the rule of lawyers, depends.8 The battle scars of history – the conflicts and contradictions, conjectures and compromises – have to be glossed over to achieve this congruence. The product of a particular socio-historical moment is generalised into an abstraction that claims to have fantastical powers of its own.9 History is subsumed into norms. To read the Constituent Assembly debates as an archive of postcolonial founding, one has to first defy the liturgy: make the constitution-making process profane by bringing it down into the realm of politics and history. “The realities and facts” of the postcolonial terrain did not allow the luxury of mimesis or a faith in the sacrality of abstract principles.10 The task of the Assembly was to construct an institutional structure on the uneven and fragile ground of the nascent postcolony. This required sober reflections on said unevenness and fragility. The fractures of the world outside pushed through the walls of the Assembly and left their indelible marks on the deliberations. Read differently, they record not the aspired coherences of a postcolonial constitution, but the turbulent tale of the Constitution of the postcolony. That tale, of hopeful anxiety or anxious hope, has two related conceptual strands, each containing its own tensions and contradictions. I identify them as two antinomies of the postcolonial transition: revolution without a revolution, and popular sovereignty without popular politics.

Accomplishing a mission

When we try to reconstruct the word-concept “revolution”, as it was used in and around the Constituent Assembly debates, we encounter a challenge. The word was evoked, in equal proportions, in two opposing senses.11 There were proclamations of accomplishing a revolution (“we are conducting a revolution”) and avoiding one (“a revolution might take the place of evolution”). It was both peaceful (“revolutions are not violent”) and bloody (“insurrections and bloodshed”). It was calm and deliberate (“deliberately aiming at a new type of society”) and disruptive and unpredictable (“not under the control of laws and Parliament”). It was a harbinger of gentle hope (“there is some magic in this moment of transition from the old to the new”) and the desperate cry of the oppressed (“there is not going to be much more waiting by these millions outside”). The word “revolution”, as used in the Assembly, pointed to two contrasting images.

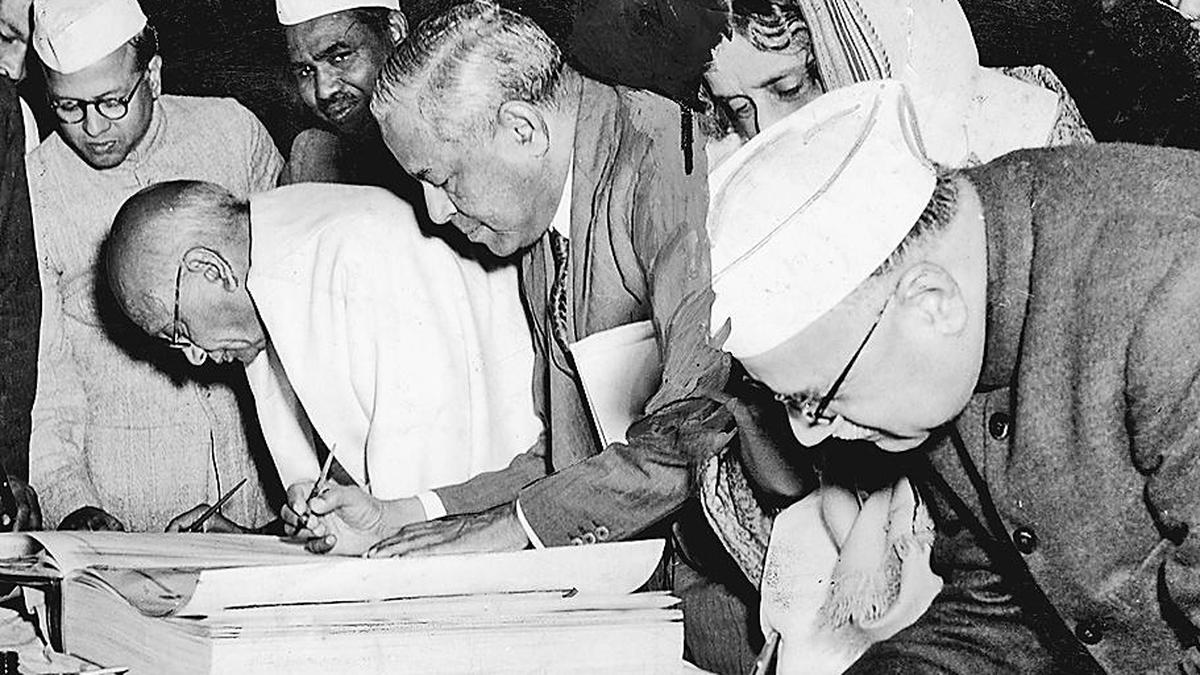

Dr. Rajendra Prasad signing the Constitution after it was passed by the Constituent Assembly.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

The first image was that of the “fire in the minds of men”, set ablaze ever since the French Revolution.12 It overwhelmed existing institutions of the state and sought nothing less than fundamental changes to both the political and the social order.13 Its temporality was rapid and unpredictable. In the words of the Russian poet Mayakovsky, it was a “march into the unknown”.14 It was unavoidably violent. And it was driven by substantial popular political activity. There are few, if any, historical events that could measure up to this image in its entirety. But as the Assembly debates testified, that did nothing to lessen the power of the image itself.

In contrast, the postcolonial founders suggested an alternative image. It shared with the first image the idea of change, but differed entirely in how that change was to come about. Its metaphor was not Dostoyevsky’s uncontrolled blaze, but the giant controlled furnaces that became the talisman of industrialisation in the 20th century. It was a deliberate project of social transformation. Its temporality was measured, controlled, and predictable. Its protagonists were not the masses in the streets but the planners in the commissions. It avoided – and this was the part that was stressed most often in the Assembly – major conflicts and violence. Finally, there was no tearing down of the old regime. Instead of being constructed anew over the ruins of its former colonial self, the state became the organiser of the project of social change. This was the image of revolution that the postcolonial founders aspired to. “People seem to think of revolutions as a big war, or a big internal struggle, violent struggle”, Nehru said. “Rather, revolution is something which changes the structure of the society, the lives of the people, the way they live and the way they work. That is what is happening in India.”15

The relationship between the two images was not just a symbolic antinomy. The former leaders of a decades-long struggle that had generated polychronic ideas of freedom and equality could not just deny or repress the revolutionary aspirations of “those unhappy millions outside”. The postcolonial ruling elite couldn’t just declare the end of a revolution that never was. So it had to substitute the (feared) first image with the (desired) second. Materially: a transformation of the social condition to forestall insurrectionary social unrest. Symbolically: Five-Year Plans and land reform legislation in place of general strikes and liberated zones.

When accused of being responsible for the violence of the revolutionary mob, Robespierre had asked, “Citizens, did you want a revolution without a revolution?”16 The Indian Constitution-makers answered in the affirmative. Robespierre had meant to signal a fatal contradiction, as the predicate (without a revolution) negated the subject (revolution) of the sentence. He meant to question whether it was ever possible to have a revolution without the tumult that accompanied it. The Indian Constitution-makers sought to resolve that contradiction by assigning two distinct images to the predicate (feared disruptive upheaval) and the subject (desired planned transformation). In the postcolonial constituent moment, the word-concept revolution was disambiguated and reassembled. It was to be change without conflict, progress without violence, history without battles. It was to be a revolution without a revolution. This was the first antinomy of the postcolonial transition. To what extent this was possible would be a question that would trouble them, and a question that would run through this book. The Constituent Assembly designed institutions around this dual image of revolution.

Popular sovereignty without popular politics

‘We, the People’ is the familiar first-person declaration of authorial identity that begins the Constitution. Most theorists of the Constitution have found little need to question this identification. Nowhere do the people author constitutions in the literal sense. The fictional ‘People’ of constitutional authorship and the empirical ‘people’ never are — nor can they be — identical. However, the distance between the two is neither predetermined nor stable. To be sceptical of the imputed authorial identity is to question the correspondence of the constituent process with the popular and democratic politics of the anti-colonial movement. The sparse critical attention paid to this correspondence (or the absence of it) corroborates the generally celebratory appraisals of both Indian democracy and the Indian Constitution over the last decades. However, the records of the Assembly debates themselves draw our attention to a persistent dissonance. When the “people” were invoked in the Assembly, it was almost always in the third person, as a “they”. “These downtrodden classes are tired of being governed,” B.R. Ambedkar said. “They are impatient to govern themselves.”17 The non-correspondence between popular politics and the constituent process would be the basis of the second antinomy of postcolonial transition.

To begin with, the popular was the condition of possibility for the constituent. There was no successful anti-colonial movement possible without popular participation – not just strategically, but conceptually. The core justification of colonial rule was the inability of the colonised to govern themselves. They had no political agency, hence they had to be ruled by a benevolent despot. The initial expressions of dissent by a professional class produced by colonial education implicitly accepted this premise. Instead of popular sovereignty, they asked for more rights and privileges within the imperial hierarchy. Their politics was, in their own words, ‘constitutionalist’. That is, whether in words or deeds, they did not question the imperial legal order. The end of the First World War saw the emergence of mass anti-colonial protests across the colonised world. When M.K. Gandhi launched his first nationwide agitation in 1919, the accent shifted from constitutional to popular. The anti-colonial cause was expressed through marches and sit-ins outside and against the legal order of the colonial regime. The prefiguration of an Indian ‘people’, through an organised movement, refuted the notion of the political incapacity of the colonised. It was an assertion of the self-making capacity of a politicised collective. Denied constitutional representation, the anti-colonial people took shape through their extra-constitutional, but organised, presence. Empires, by their own logic, could not abide by popular sovereignty; only govern subjects. Hence, popular sovereignty and democracy were concepts inherent to the logic of anti-colonial articulations.Its most significant institutional legacy was universal adult suffrage, instituted immediately after Independence — a monument to popular politics.

At the same time, popular political activities — when the imagined people of India took concrete shape in the streets and squares — multiplied the meanings of freedom after empire. The masses could not be viewed as passive receptors of nationalist ideology. In persistent rebellious expressions of their political subjectivity, they painted pictures of liberation in terms of “what was popularly regarded to be just, fair and possible.”18 These terms were more often than not unsanctioned by the Congress, generating anxiety amongst its leadership. A simultaneous dependence on and apprehension of popular mobilisations became the central tension of the anti-colonial movement. Each pole of that tension exerted itself on the trajectory of the struggle. One demanded national liberation through intensification of the mass movement and no negotiations with the colonial rulers; the other called for a retreat from mass mobilisation and a transition of the Congress into a party of government in waiting. These were the two political idioms of decolonisation, and consequently, postcolonial futures. In the words of Frantz Fanon, the choice for the anti-colonial party was to either be “an administration responsible for the transmission of government orders” or to be the “energetic spokesman and the incorruptible defender of the masses”.19 The Congress, like most of its anti-colonial peers, took the first path. Yet the subterranean pressures of the latter could not be ignored, as-yet-unsettled aspirations of freedom circulated outside the Assembly. The years around Independence were the times of the most intense and militant mass struggle in India’s history, with various creative syntheses of the language of anti-colonialism with demands of socio-economic emancipation. When, soon after Independence, Nehru advised workers in Calcutta to withdraw their strike, they responded: “We have had enough of bullying and threats from imperialist rulers. It was from Panditji [Nehru] that we learnt how to react to it. Panditji may change, but his lessons are still clear and inspiring. We will rise a thousand times stronger against your threats, Panditji! Till you meet our legitimate demands and let us live honourably in free India.”20 The anti-colonial threatened to infiltrate the postcolonial. Consequently, the postcolonial order was born in “fear and trembling.”21 The insurrectionary spectre of the absent masses haunted the constituent process and shaped the Constitution.

Any critique of the ‘absence’ of the people from the constituent process must contend with the apprehensions about the unmediated ‘presence’ of the same. A “people as one” in Hannah Arendt’s words; a “bad metaphysics of the people” as Franz Neumann called it.22 However, the adjective (popular) concerns my argument more than the noun (people). These popular political forms were not ‘metaphysical’, nor were they predetermined. They were generated by and through the anti-colonial struggle, and were available to the Constituent Assembly (as they are to us) as historically concrete figurations. The constitution of the nascent democracy incorporated several curated practices for political participation. What remained outside, however, were the various forms of mass mobilisations used during the anti-colonial struggle, including the rallies, strikes, sit-ins, and hartals common during the Gandhian movement.23 Under the new Constitution, the masses could vote, but there were no structures that enabled them to emerge as a collective agent outside of electoral aggregations.

This self-fashioning conception of democracy was immanent in the anti-colonial struggle, even if unrealised. The anti-colonial ‘popular’ was not a synonym for spontaneous and unorganised. The anti-colonial struggle became generative precisely because it was mobilised and organised. The point was not the denial or incomprehension of institutions as such, but opposition to institutions imposed, undemocratically. Not the extra-institutional, but the self-institutive capacity of popular political activities was what was at stake. The postcolonial Constitution-makers sought the authority of popular sovereignty, but without popular politics.

Sandipto Dasgupta is a political theorist and is currently with the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey