On November 29, the world awoke to the devastating news that the much-loved British playwright, Tom Stoppard, had passed away. It is understandable that the news shook the U.K. theatre community, but it also sent waves of mourning among many of us stage practitioners around the world.

In popular culture, Stoppard is immortalised by his Oscar win (Best Original Screenplay) for the 1998 period romcom, Shakespeare in Love. At the time, many wondered who this strange man was. But for us theatre-wallahs, just a sample of the film’s dialogue, immediately characterised by a deft turn of phrase that only Stoppard possessed, was enough. That award was an acknowledgement of his genius from the mainstream, but it gave us a reason to wear smug grins since we were ‘in the know’ of his mastery from much before the film.

A still from Shakespeare in Love (1998), starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Joseph Fiennes.

My first brush with Stoppard’s work was the ridiculous farce, On The Razzle, an adaptation of another play, I was to find out later. But the bizarreness of the scenes was brilliantly offset by the charming dialogue — full of puns, repartee, and double entendre. For my teenage brain, it was a goldmine. I loved the way he connected words. Homophones allowed him to make hilarious exchanges like:

“I love your niece”

“My knees, sir?”

Stoppard taught me that the real tool of communication in theatre is not the rambling soliloquy or the beautiful descriptions; it is the dialogue.

For most of us ‘Lit types’, college is usually where we first encounter Stoppard. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (1966) is a seminal work of absurdist literature, but unlike Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot (1952), it seemed much more accessible and identifiable. Existentialism became understandable. When Atul Kumar finally staged his vibrant version with actors on stilts, at the NCPA Experimental Theatre in Mumbai, 1998, I was riveted. The play leapt off the page and became urgent, vital.

Joshua McGuire and Daniel Radcliffe in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, directed by David Leveaux, London, 2017.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Rock music and mathematical logic

What’s more is that Stoppard was a contemporary playwright, a modern master who was still contributing to his canon. That gave him an aura of coolness, and gave us our poster-boy of theatre.

While still in college, a dear friend introduced me to the absolute immediacy of Albert’s Bridge — a play about a philosophy major who is more happy painting a bridge than having to deal with his day-to-day tasks. Stoppard satirises education, class struggles, corporate or government decision-making, and even mathematics that doesn’t account for the human being. The friend eventually staged it as a college production at St Xavier’s Auditorium in Mumbai in 1998, and working on it and watching rehearsal impacted me in a very powerful way. I still find myself quoting lines from it to relate to my everyday experience. It’s a play that I had hoped to eventually stage in Hindi, but I am yet to find the courage.

Some of Tom Stoppard’s plays.

It’s a pity that more of his work hasn’t been staged in India, especially given the fact that he spent some of his younger years in Darjeeling. This might be due to the difficulty in obtaining rights, or perhaps that changes/ localisations are often not encouraged. Other than Rosencrantz, or The Real Inspector Hound, there haven’t been too many Indian productions.

Perhaps my favourite Stoppard memory is a production of Rock ’n’ Roll at the Duke of York Theatre in London, 2006. Other than its enticing title, or the fact that the production had Brian Cox and Rufus Sewell, the real magic is that it is a political play, but about rock music. I don’t think I have ever paid as much for a theatre ticket. It was a last-minute impulse, and the seats were ‘restricted viewing’. But despite the obstructing pillar, I was transported to Cambridge and to Prague seamlessly as the play talked about the role rock music and, particularly, Pink Floyd played in the Czech resistance against communism. Stoppard’s writing is greatly researched, unusual in theme and almost always feels urgent and necessary even though it’s talking about a time long ago.

I felt the same when I watched Arcadia in London in 2009. Although written in 1993, and talking about the early 1800s, the play somehow predicts the future. In an early scene, a character describes a leaf. And in doing so, she literally lays out the modern mathematical logic for algorithms. The very same algorithms that now control our entire lives. In some ways, the play is a homage to the phrase ‘the sciences tell us how the world is, while the arts tell us what the world can be’.

Absurd yet poignant

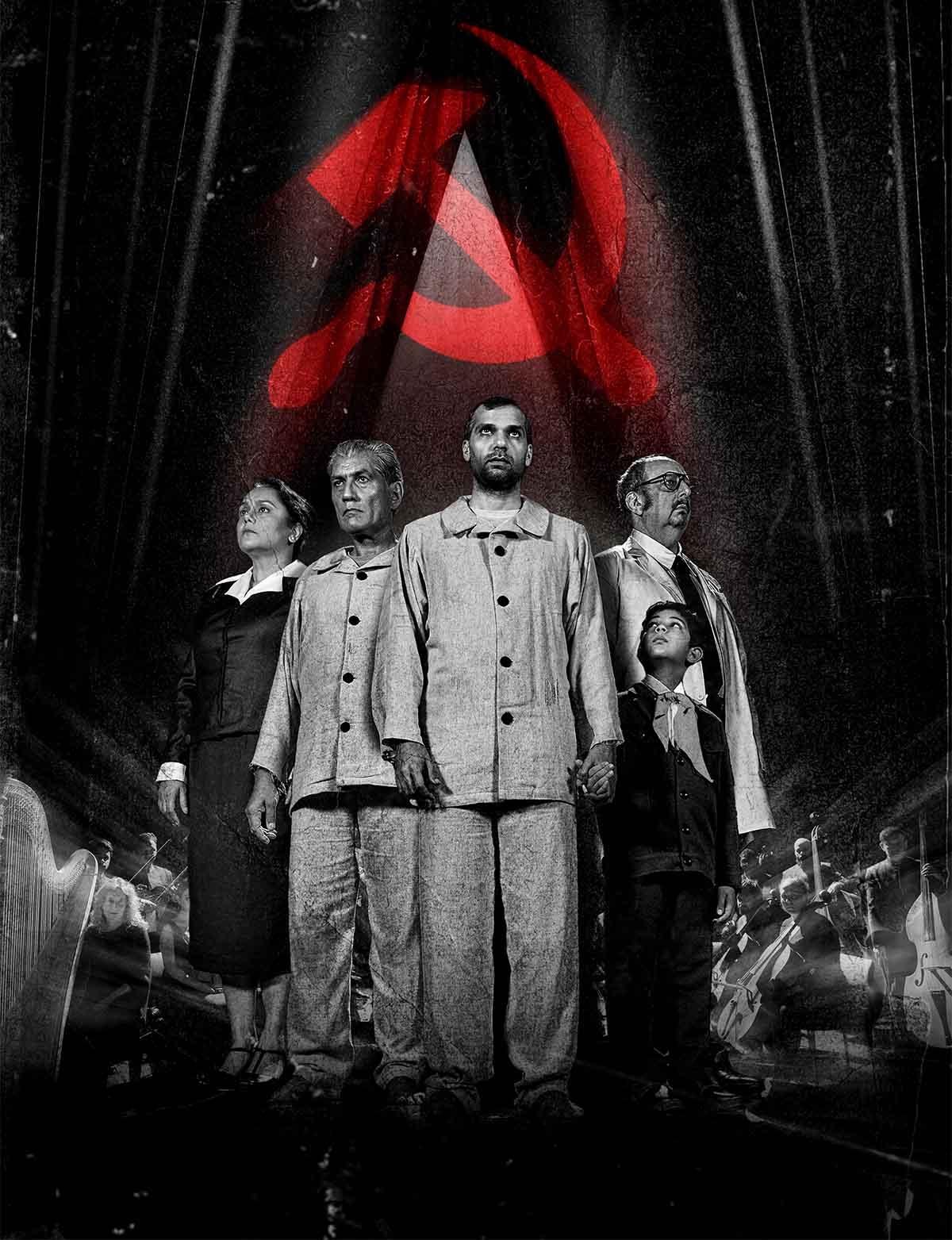

A poster of NCPA’s 2022 production of Stoppard’s Every Good Boy Deserves Favour, starring Neil Bhoopalam and Denzil Smith, in Mumbai.

The most recent Stoppard production I saw was the National Centre for Performing Arts’ ambitious Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (2022). Most of the play is set in a jail cell, but it uses a full orchestra. It is set many years ago in Soviet Russia, but why do the absurdity of the bureaucracy and the totalitarian ideas seem, once again, so current, so… India?

Stoppard was not just a playwright for the ages, he was also in many ways the moral conscience of our time. He spoke truth to power, but with humour and satire. He made us realise that it wasn’t his characters that were trapped in absurd plots, but us who were living in them.

A few years ago, while lighting a stage production of his tele-play, A Separate Peace, I remember having to pause because I was floored by a snatch of dialogue between a nurse matron and a patient in a hospital.

“I’m glad you feel at home”

“I never felt it there”

On the one hand, it made no sense. And yet it seemed to encompass a feeling all too familiar.

Stoppard’s magic was that he could be absurd and poignant at the same time.

The writer is a theatre director and shares Tom Stoppard’s love for puns, theatre and cricket.

Published – December 04, 2025 04:37 pm IST