Succulent, mildly spiced chunks of lamb, nestled in sweet ghee-washed long grain rice arrive in gold bowls. This is Yarkhandi pulao, stark white and studded with meat and whole spices. It travelled along the Silk Route, and is one of Chinese nobility’s most luscious gifts to Ladakh. As local legend goes, tradesmen once dabbed ghee on their lips like balm since true wealth was measured by how much of it dripped from your elbows after two bites.

How many generations does it take to forget this opulent dish?

Stanzin Tsephel, founder, Stonehenge Ladakh, says “just one”.

Yarkhandi pulao from Namza dining

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

During our walk along Leh market, this hotelier who is a passionate advocate for Ladakhi culture, stops to point at a number of shops and cafes that have mushroomed in the last decade. “You will find momos, noodles, dal chawal, and chilli chicken here. Is this the food of Ladakh? I’d argue otherwise,” he says.

One of globalisation’s greatest casualties is authenticity; its collateral damage, culture. Since the 2000s, as tourism began thriving in Ladakh and development entered the conversation including better roadways, sewage systems, and high-altitude passes that now function year-round, two important ingredients central to India’s diet became readily available at the union territory: rice and fresh vegetables. Rice and its supply through the Public Distribution System (PDS) scheme has immensely aided the average Ladakhi in the way of cooking quicker meals. In the process though, an entire cuisine seems to have gone missing.

“This wasn’t the case before,” says Padma Yangchan whose venture Namza Dining brings traditional Ladakhi food to the fine diners of the world. She remembers purchasing a kilo of tomatoes at an alarmingly high rate of ₹400 when she was a young girl. “Earlier, families would dehydrate and store herbs foraged according to the season, particularly summers, and save them during the winters when it was hard to grow food and harder to commute across the Union Territory. We’d do the same for tubers — carrots, turnips, potatoes, and the likes,” she says.

While both Padma and Stanzin are thrilled about development as it paves way for increased tourism — a sector that they depend on for their livelihood — a casualty is the meals that they grew up eating.

It is why an important movement in Ladakh has sprung up, one where chefs, hoteliers, and cooking enthusiasts from the region, are combing through phone books, and traversing this region’s expansive mountains and valleys, to speak to grandmothers, uncles, neighbours and strangers, to preserve recipes that once soothed several generations.

Here, buckwheat, barley, wild garlic, chives, nettles and capers, rule the roost. In a country where measurements cease to exist and are assessed by the handful, documenting the food and presenting them in cutlery palpable to an audience that perceives this culture foreign, has been nothing short of an adventure. It is one that every single one of them is intent on taking up.

Around the fire

“Each of Ladakh’s seven divisions has its own cuisine, distinguished entirely by each tribe. What is staple in Sham Valley is entirely different from Turtuk, where I am from. We are from the other side of the mighty Karakoram range, part of the Greater Gilgit Baltistan belt [stretching all the way from Afghanistan to China],” says Rashidullah Khan, the founder of Virsa Baltistan, a boutique property along one of India’s last village before the Pakistan border.

A local pasta in a broth of vegetables and meat at The Heritage Kitchen

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

After having spent years in Japan and Bengaluru, Rashid came back home to Turtuk, intent on showing people the bounty that his village had to offer — people and fresh produce. At his property, where The Balti Farm is located, women from Turtuk who cook meals at home, make a course-based meal full of fresh fruits and vegetables at the hotel for an authentic Balti experience. These include salads, hand-rolled noodle soups with chuffa (a dry cottage cheese), buckwheat pancakes, and praku, a pasta made with a creamy walnut sauce. The meal usually ends with a fruit-based dessert.

If you are lucky enough, during apricot or apple season, pick them off trees for a post-meal snack. Since Turtuk became part of India only in 1971 post the Indo-Pak war, women of the village remain custodians of a cuisine that goes beyond war and long-geographical boundaries. “I call my relatives, many of whom live across the border, for some recipes too,” he adds.

Much of Chef Jigmet Mingyur’s cooking is influenced by the time he spent cooking at Kathmandu’s Zhichen Bairo Ling monastery, where he was a monk for two decades.

“In the monastery I learnt that the produce must shine,” he says. This ascetic who gave up his robes to become a chef, forages for herbs in mountains and hills near his restaurant Tsam Khang in Leh. Having come from the village Khemi, in the sand dune-laden Nubra Valley, (only 30 kilometres from the Siachin Glacier), the Ladakhi chef is an expert at making the tedious churpi, or cheese made from Yak milk. During winters, Jigmet does two things: speak to family about other old recipes, and travel to different parts of India for a pop-up.

“Ladakhi food is medicinal. It was created to heal during the cold and fill our stomachs during days when the next meal was six hours away. It is why you find the likes of nettle, and capers in our cuisine. When I travel to other cities for popups, my boxes are full of dehydrated fruits, vegetables and herbs. There is something about the air and water in the mountains. Even our turnips are delightfully sweet,” he says.

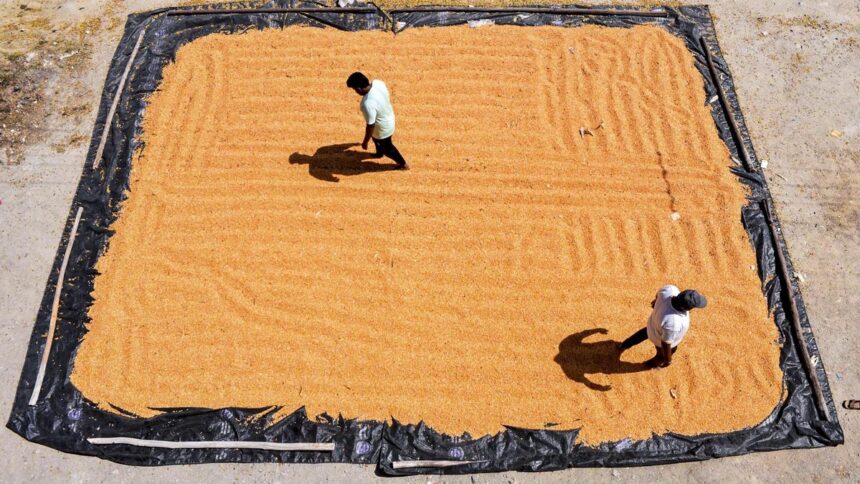

Women from Turtuk preparing meals for Virsa Baltistan’s The Balti Farm

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Chef Nilza Wangmo agrees. Having come from Sham Valley in Ladakh, Nilza is used to premium meat from yak and lamb, dehydrated over a fire and stored for difficult winters.

Her eponymous restaurant located in Alchi, the village she grew up in and it serves delectable soups, and meat-based fare. “I learnt most of my recipes after having assisted my mother and grandmother in the kitchen. Serving yak is banned now but the process of curing and dehydrating meat is quite the task. Now we serve mutton and lamb. You should try the Ladakhi mok-mok [a version similar to the momo] and paba, a doughy multi-grain bread served with thangthur, a yoghurt made from the shoots of capers. We interestingly discard the caper itself,” she says, speaking from Japan where she is hosting a Ladakhi popup.

Stanzin Tsephel, who runs The Heritage Kitchen in Nubra Valley invites us to his family home where the kitchen is the centre of the house. “We saved this home from demolition and we now realise that very few homes have Ladakhi architecture. How times have changed,” he says, as we slurp on noodles made of barley with pieces of peas and potatoes. Stanzin says that both he and his wife have been seeking out family recipes as many people in Hunder, where his property is located, are related to each other. “It is full of trial and errors though. Nobody uses measurements in India,” he says, chuckling and lamenting at once.

Namza’s Padma states that the measurements are hardly a concern when documentation is lax in remote places like Zanskar valley, home of the snow leopards. “But that is where the most interesting meals exist. During one of my visits, I learnt of the gyuma that is interesting, made with minced mutton and also blood. We serve one without the blood at Namza because where do we go looking for blood? It will be too barbaric, no?” she says.

Her favourite story is how she snagged the recipe for Yarkhandi pulao, now on every Ladakhi chef’s menu list. “My neighbour used to make this pulao at home and he would call it the Hor pulao. Hor or Horpa refers to the community originating from Yarkhand, while also referring to the region. Imagine going to a fine dining space and asking for this dish,” she says, cackling. Then adds, “The food from this region has always been exceptional. Our aim is to take it to several parts of the globe. For now though, we want it to fill every Ladakhi’s plate too.”