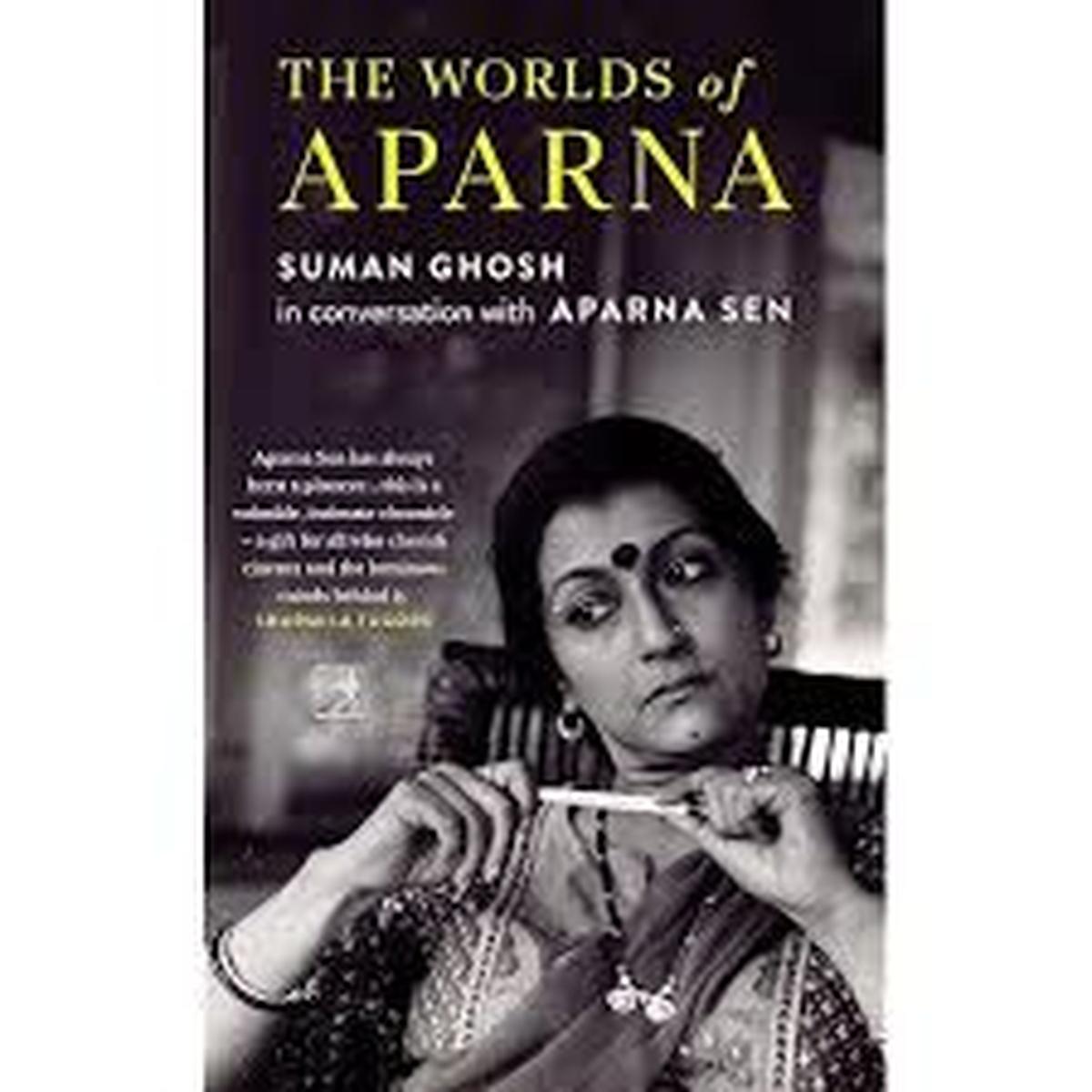

The book cover

Movie lovers will remember her as the playful young girl rummaging under the bed to look for her pet squirrel who has chosen the right moment to slip out and gatecrash a nuptial negotiation. She finds Chorki in a matter of moments and darts out, leaving an already nervous family that has laid out a charm offensive for a prospective groom in a state of befuddlement.

Aparna Das Gupta in “Samapti”, directed by Satyajit Ray, the third chapter in the triptych Teen Kanya in 1961.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

It is one of several comedic moments in Samapti (Conclusion), part of Satyajit Ray’s triptych of Tagore short stories — Teen Kanya (Three Daughters). Aparna Sen, was only 14 when she played Mrinmoyee in the short film that pivots humour in the institution of marriage in familiar social settings. The year was 1961.

From playing the heroine in popular Bengali films to holding her own with stalwarts such as Ray and Mrinal Sen, Aparna is one of the legends of Bengali cinema. In between, there’s been theatre, both serious (with Utpal Dutt, no less) and mainstream, activism and a nearly two-decade stint as Editor of Sananda, a trailblazing women’s magazine. The next major shift was writing short stories. One modelled on her school principal wrote itself into a screenplay. Nurtured over two years, it was a labour of love that had to be made into a film.

Jennifer Kendal in a still from 36 Chowringhee Lane

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

36 Chowringhee Lane was born, placing itself in the central Calcutta neighbourhood to allude to the protagonist’s Anglo-Indian roots but brilliantly suffixing a fictional lane to its title. The film was released in 1981, and Chowringhee Lane was so earnestly imagined that it has etched itself into the multi-cultural landscape of the city. A stellar debut, 36 Chowringhee Lane will remain one of Indian cinema’s most enduring portrayals of the individual, her solitude and parched existence universalised with honesty and empathy.

Aparna has so far directed 16 feature films, including such landmarks as Paroma, Yugant, Paromitar Ek Din, Mr & Mrs Iyer, 15 Park Avenue, Goynar Baksho, Ghawre Bairey Aaj and, recently, The Rapist. She has been able to widen her lens on life with each outing, placing her women in unchartered territory within relationships and politics, allowing them agency and voice. Three National Awards have come her way in addition to the NETPAC Jury Award at the Locarno Film Festival.

Auteur by instinct, Aparna makes sure her films bear her imprint, because she believes her directorial offerings and not her screen idol status define her legacy.

At 80, Aparna still sparkles. “I don’t feel my age and people say I don’t look my age. So, I am really not bothered,” she says in filmmaker Suman Ghosh’s commemorative book The Worlds of Aparna (Simon & Schuster India), which records his conversations with her, daughter Konkona Sensharma, husband Kalyan Roy, film friends Anjan Dutt, Goutam Ghose and Shabana Azmi, and author/cultural commentator Samik Bandopadhyay.

The book cover of Aparna Sen: A Life in Cinema

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Another timely book, Aparna Sen: A Life in Cinema (Rupa) by Devapriya Sanyal, undertakes a deep dive into her filmography, especially with regard to her female characters. These are women who may start off emotionally vulnerable but by the end of their on-screen journey almost always claim agency for themselves. Read together, these books offer a cogent analysis of Aparna Sen the filmmaker, placing her within the framework of contemporary Indian directors. They shine a light on the person she is: funny, at times irreverent, and offer intimate accounts of her formative years in Calcutta and Santiniketan.

Aparna grew up amid books, music, poetry and films, courtesy her parents Chidananda and Supriya Dasgupta. Their home was a crucible of the arts with poets, writers and cultural icons visiting often. It was but natural for her to imbibe a sense of aesthetics closely associated with the Bengal of the time. Her father and Ray were friends, and together founded the Calcutta Film Society, making them pioneers of the film society movement in India. There were regular film screenings at home (the works of Ingmar Bergman, Sergei Eisenstein, and more).

The first Bengali film she was “allowed” to see was Ray’s Pather Panchali, Dasgupta Senior being quite clear that his children needn’t be exposed to the formulaic offerings of commercial cinema so early in life. Yet, she spent around 20 years in that very milieu as an actor.

Aparna is a keen photographer, and a good one at that (the Henri Cartier-Bresson books at home helped), which explains her instinctive understanding of light and camera angles. “Now, we’ll have to take her seriously,” commented Ray when she showed him her black-and-whites. Sadly though, there’ll never be an exhibition of her stills as she has lost most of the negatives (“I am not much of an archivist”).

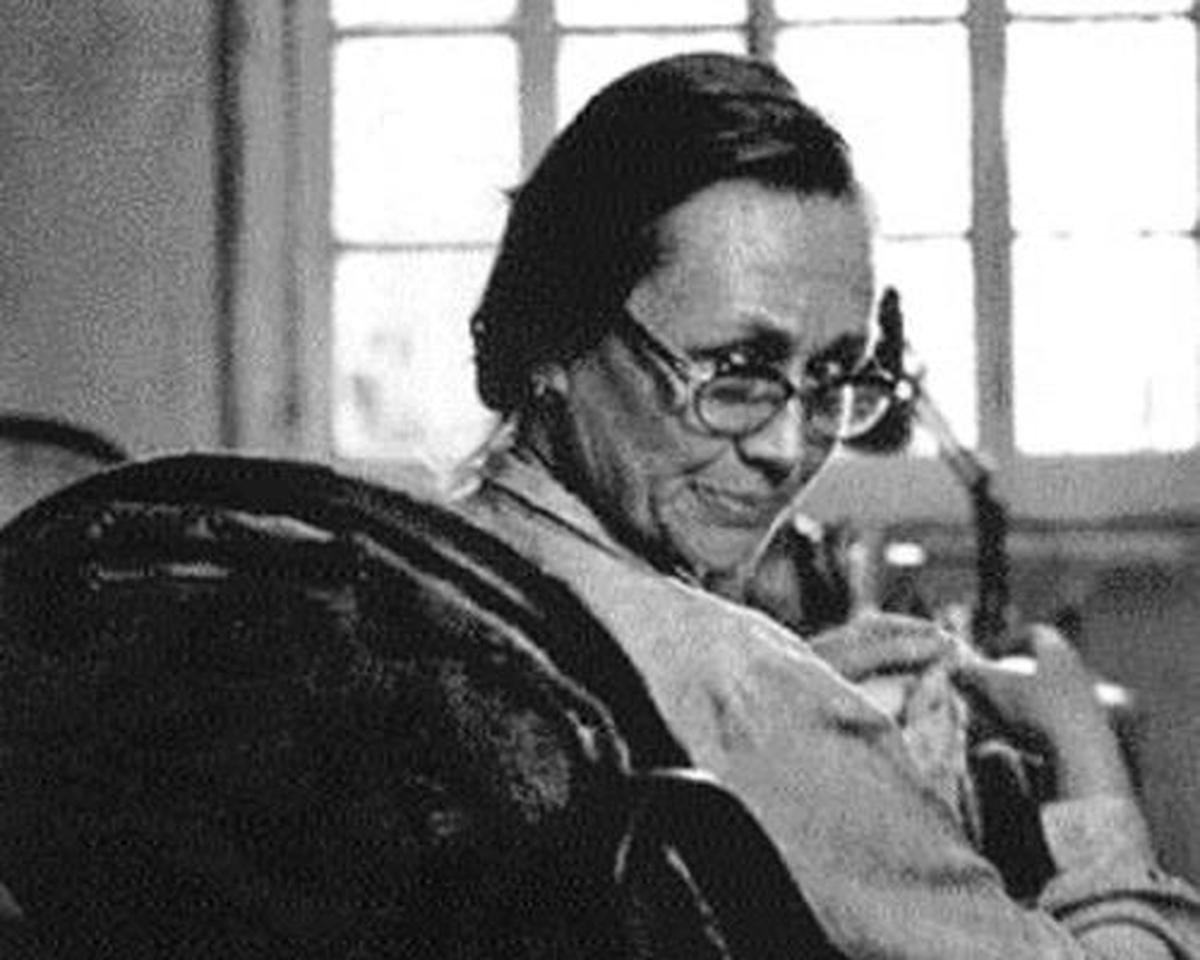

The director during the shoot of Mr. & Mrs. Aiyer

| Photo Credit:

PARTH SANYAL

Who did she go to with the completed script of 36 Chowringhee Lane? Ray, of course. He liked it. It’s all heart, he said, and put her on to Shashi Kapoor. But, how did Aparna read her script to the Kapoors in Bombay? When did he agree to produce the film? Why did he double Aparna’s directorial fees?

Suman Ghosh’s book is delightfully revelatory. Beginning with the pastel-shades of Ms. Violet Stoneham’s loneliness, Aparna’s ever-widening world view gets reflected in the sheer range of her stories and characters. Meenakshi Iyer rediscovers her humanity while encountering a riotous mob during a bus journey (Mr and Mrs Iyer, 2002), homemaker Paroma (1985) is able to take responsibility for herself, choosing to return after a torrid affair, as Devapriya explains, “to continue to search for her own identity”; Deepak and Anashua find their marriage crumbling (Yugant, 1995), their downslide finding metaphoric resonance in the way environmental recklessness destroys planet earth – the Gulf War, and oil spill were Aparna’s inspirations; a mother-in-law bonds with her daughter-in-law (Paromitar Ek Din, 2000), their friendship helping each other navigate relationships in a patriarchal family. As for Meethi, disturbed on account of a mental health condition, she ultimately takes charge and simply disappears (15 Park Avenue, 2005), a stunning on-screen resolution that left theatre audiences transfixed long after the end credits had rolled.

A still from the film The rapist

“It’s my worldview that you must soak up life like a sponge,” believes Aparna, “then, every experience becomes your resource material that you, perhaps, someday may go on to use.” She has lived by that credo, unafraid about where it might lead her. Consider Ghawre Bairey Aaj (2019). For this modernist retelling of Tagore’s Home and the World, Aparna drew from contemporary reality to arm Bimala, the female protagonist, like she had never been imagined, to reflect the filmmaker’s vehement rejection of the politics of hate sweeping the world today.

Where exactly does Aparna feature among India’s filmmakers? For Shabana Azmi, she’s among the finest we have. “She grew up in a very syncretic atmosphere… and it hurts her as an Indian to redefine that,” she explains. Anjan Dutt believes youngsters will come to regard her films as important a document as her cinematic predecessors. Most of all, critic Samik Bandopadhyay emphasises, Aparna stands out as she is among the very few filmmakers who remain political. “…Aparna has dared. And her politics lies there… in daring to do what few others are doing.”