“He was lonely.” Artist Premalatha Seshadri discusses a mutual friend, as she gently lifts sprawling canvases at her home studio. “He had a lot of friends,” I respond blithely. There is a thoughtful pause. “You can have a lot of friends and still be lonely,” she counters.

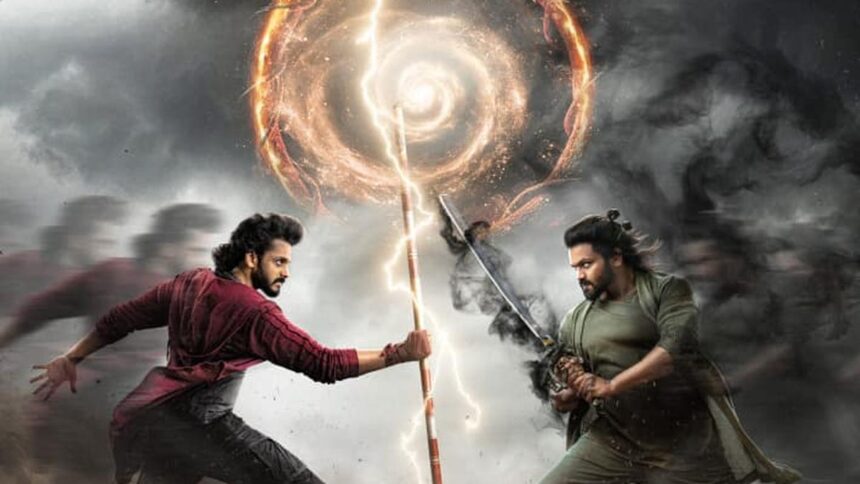

As she talks, she grapples with the next big canvas, spreading it on the ground, so we can admire it together. Done in her signature minimalist style, it features two leggy birds drawn in black with precise lines and dots, then feathered with a flurry of earth brown lines. The work is joyous, and just a bit cheeky: a refreshing break from art that takes itself too seriously.

Like the artist, who writes poetry in her spare time, the piece is thoughtful and perceptive.

I am spending the morning with Premalatha, at her serene home set a few minutes away from Cholamandal Arts Village, from where the Madras Art Movement surged. We met at the launch of her retrospective, currently on at Ashvita Art Gallery, titled The White House By The Sea. Elegant and self-composed, in a striking string of pearls, she greeted fans demurely, only breaking into laughter when in conversation with Thota Tharini, her classmate, as they catch up on stories of old friends.

The show, curated by Ashvin Rajagopalan, gives visitors a fascinating glimpse into five decades of her work across multiple mediums. The daughter of a former Mayor of Bangalore, Premalatha started to paint as a child, and the 13 canvases in this exhibition trace her path, showing how she moved from restless oils and landscapes to restrained lines that pulse with energy.

Premalatha Seshadri’s work

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Now in her seventies, she lives alone, enjoying solitude at her white house by the sea, which is visited by a cacophony of birds everyday. As one of her poems puts it: ‘Haughty hoopoes, preen, strut/ it is a hot and violent summer/ crows and peregrine falcons fight for territory, wildly raucous in a dizzy spin in my front yard.’

She says, “We moved here more than 40 years ago. My late husband, Mr Seshadri owned land here, and I wanted to be free of landlords. We had casuarina forests around us then. And our only neighbours were the Whitakers at Madras Crocodile Bank and the Cholamandal artists.”

This was nearly five decades ago. Over the decades, she worked relentlessly on her art. “Living here, my natural surroundings, my Injambakkam landscape… they influence my work. My art is a record of my visual vocabulary,” she says. Then adds, “I like my privacy. I am also in one sense a loner. You need that privacy to be creative. That is the reason Mr Paniker started Cholamandal.”

Although Premalatha studied under KCS Paniker in the late 1960s at the Government Arts College, Madras, and is one of the few successful women artists from that generation she still sees herself as an outsider. “There is no such thing as fitting in. I come at the tail end of the Madras Art Movement. All of us who were physically not living inside the area of the artists village, were really not in the orbit.”

She adds, however, that it was an exciting time. “People were ambitious and trying to locate an identity. It was the beginning of a distinct Madras style. Intellectually these artists wanted to give an Indianised visual representation of art, using their gifts as painters or sculptors. Their work was totally different from the strong European movement which had captured the Western world. They were really pioneers.”

Premalatha, known for her strong lines, says they are a distinctive feature of the southern artists

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Premalatha, known for her strong lines, says they are a distinctive feature of the southern artists. “They had great control of the line. I do feel that total abstraction has only developed only after a period of working with the line. However abstract a picture may be there is a division of colour and that is the line. Think of KM Adimoolam’s early line drawings, Achuthan Kudallur’s control of colour, and RB Bhaskaran’s individualistic forms… Younger artists today are beneficiaries of these artists.”

The fact that a group of some of the movement’s most prominent artists lived and worked together at Cholamandal helped give the movement momentum. “Paniker was the nucleus. He was the voice for these people who did not really know in which direction to go, apart from learning the skills that gave their artistic abilities a voice. He had a vision and was very sincere to that. He suggested craft — and also fine arts, which would help artists who settled there to support themselves.”

Premalatha does not see herself as part of this movement. “I am an outsider, because I lived here. But I am a colleague and a former student of the Government Arts College. And I used to maintain a studio there.” However, she adds, “The collective was for the people who lived over there. It was very territorial. Not completely friendly to a female colleague.” That said, she adds that there were two women who did memorable work from there: Anila Jacob and Arnawaz Driver. She also talks of TK Padmini with admiration.

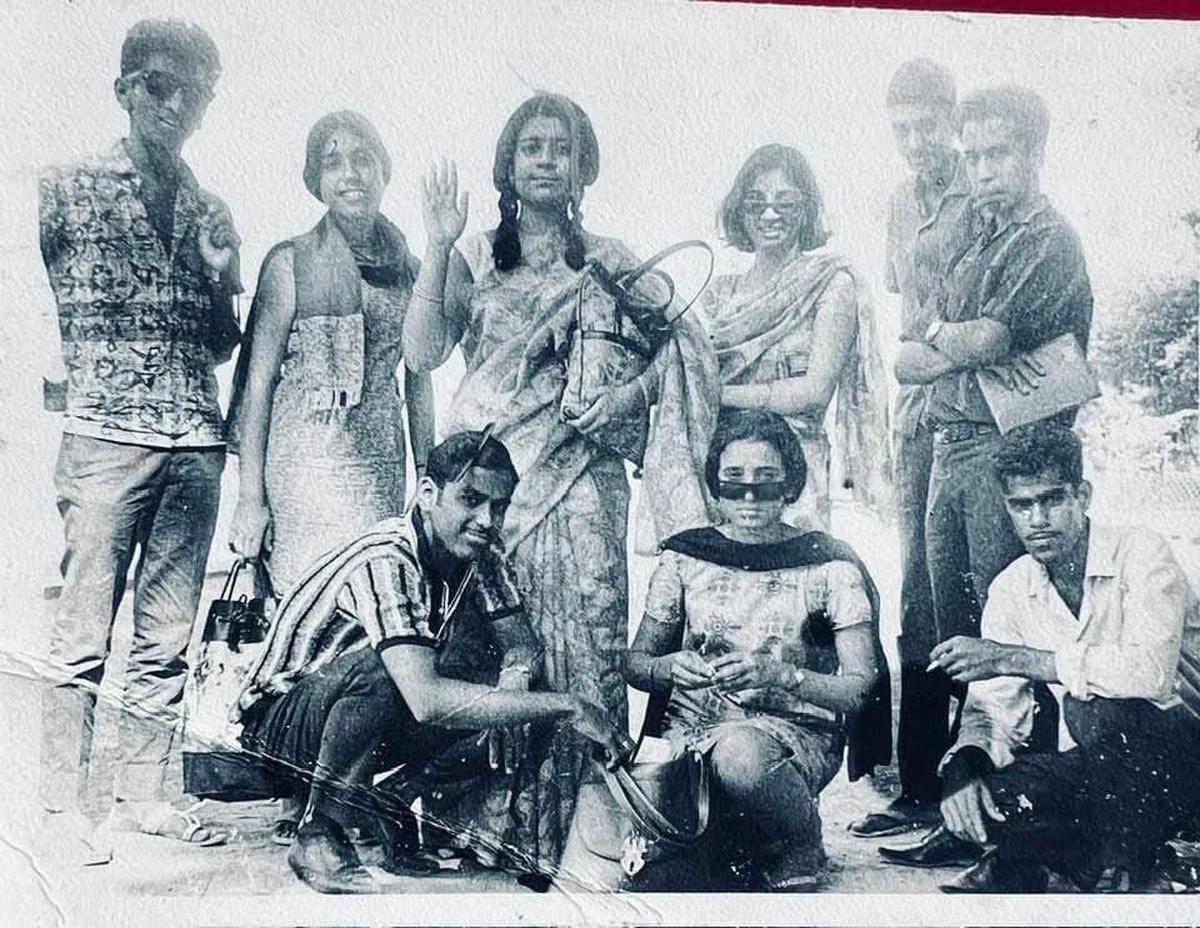

The Class of 1970 Madras school of Arts on a nature study and painting trip. From right Thota Tharani, P. Gopinath, Premalatha Seshadri, Zarina. Sitting Peter Gangadharan, Dachu and Pressanna

| Photo Credit:

Photo courtesy: Artist Peter Gangadharan

“The only art gallery in Madras was Sarala’s in Connemara” she says, adding “It was a struggle to be represented. It was a very very lonely journey. And it was definitely not financially viable.” Nevertheless, her style flourished. “In the ‘60s I was fascinated with textures, then I abandoned them to concentrate on the line. I did a series called Zen Water. These were illustrations of things I associated with life in water: Fish, turtles and other aquatic life.” Soaking in her surrounds, she also chooses to work with earth colours: terracotta, black and white.

Thinking back she says working alone benefited her art. “If I was within the arts village, I would have been a clone. I probably would have been heavily influenced… Each person has a visual vocabulary. Mine is so different from my contemporaries. It’s not decorative. It’s very simplified. And minimalist.”

Half a century after the Madras Art Movement began, Premalatha is still working. As I leave, she gets back to contently drawing birds at her quiet white house by the sea. A reminder that solitude need not be lonely; it can also be deeply inspiring.

The White House By The Sea is on till October 31 at Ashvita’s, 2, Dr Radhakrishnan Salai, Mylapore.

Published – October 08, 2025 04:43 pm IST