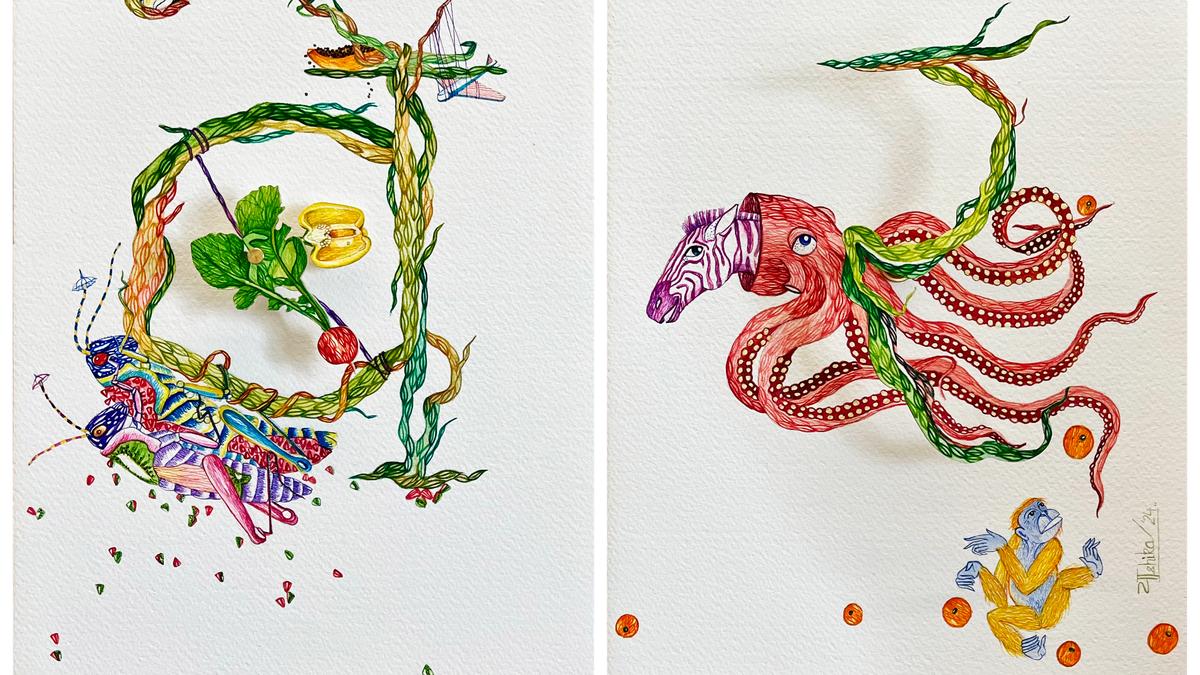

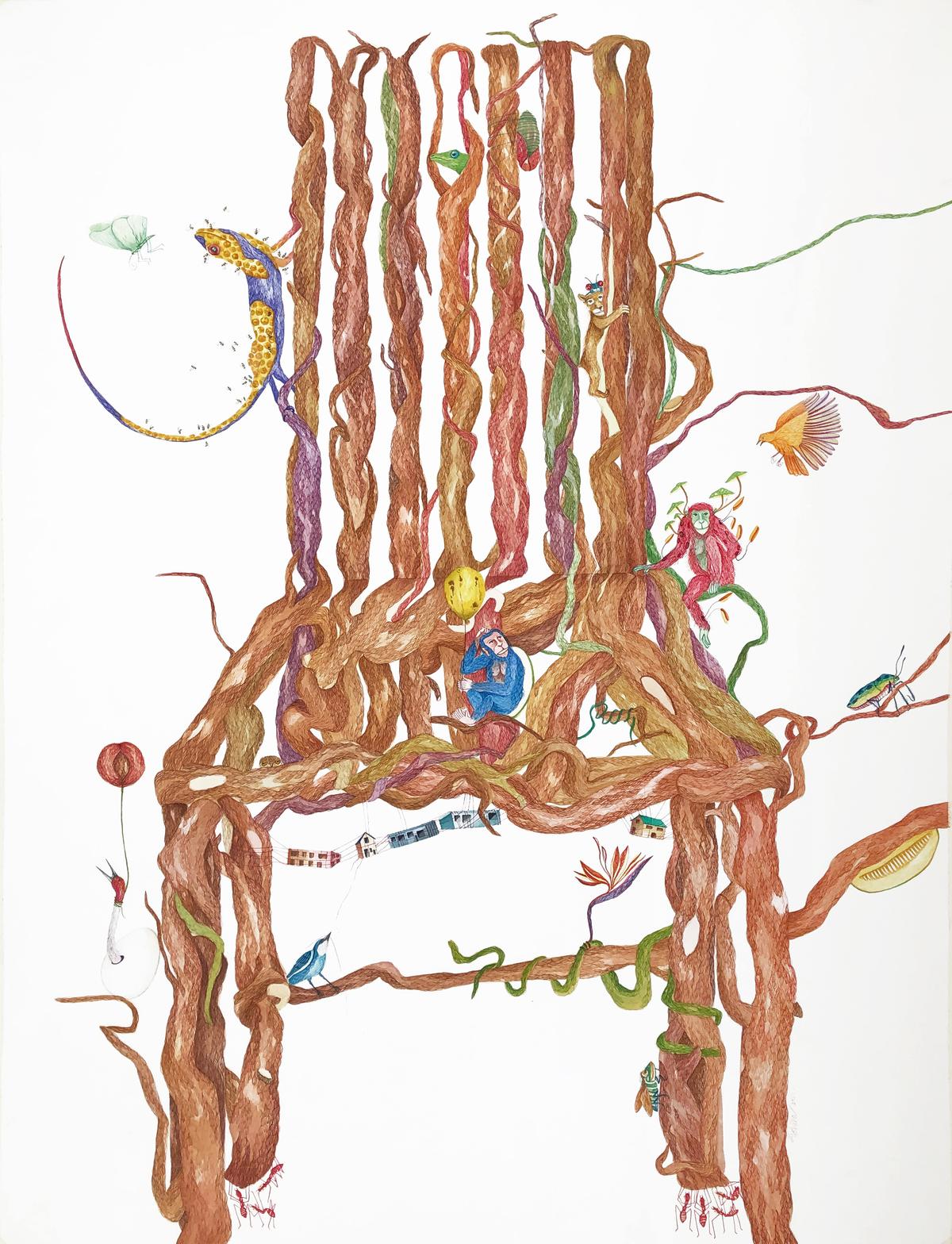

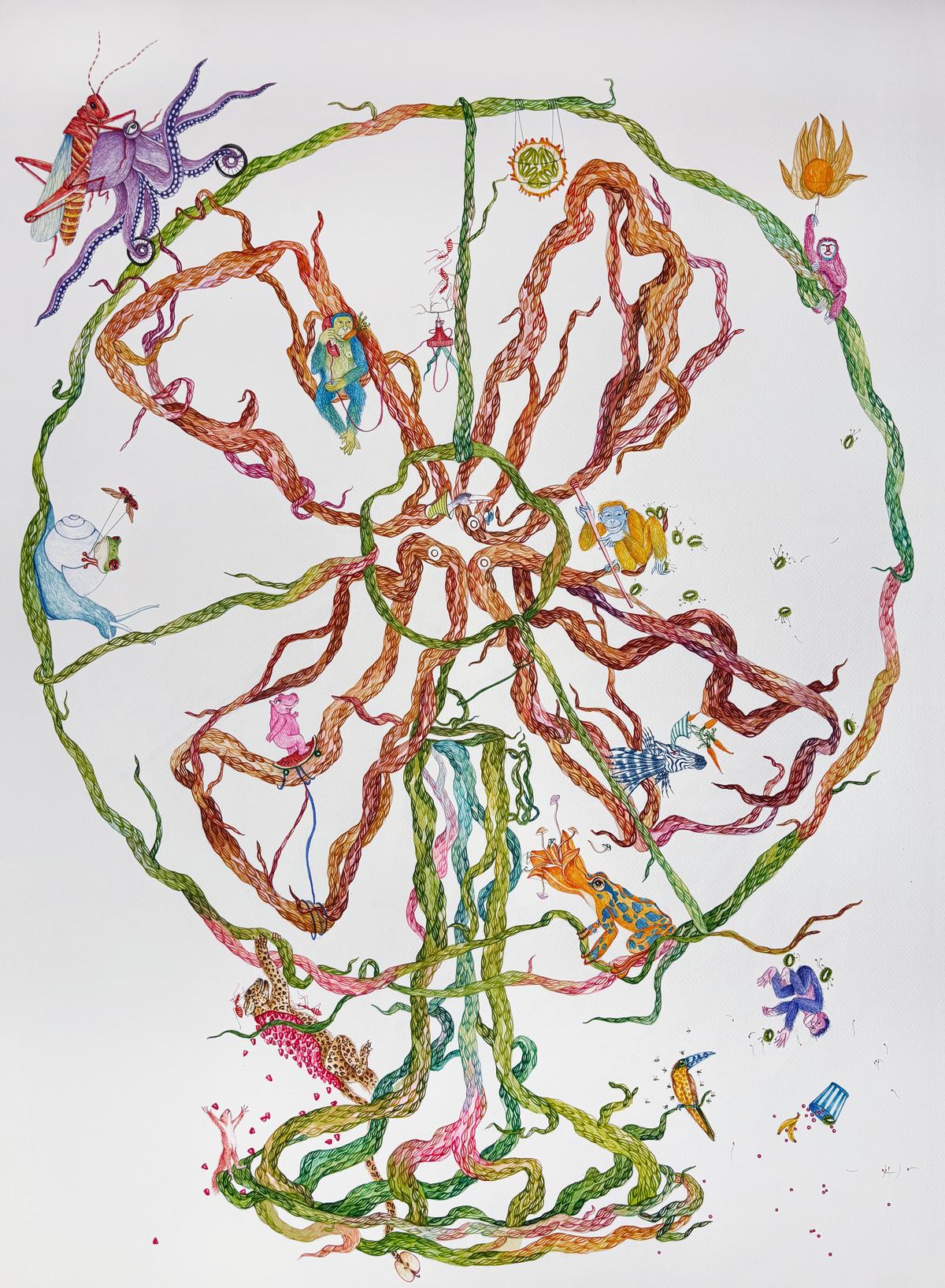

“I think I live in my own wonderland,” Yashika Sugandh says. Or, as she sometimes calls it, her “la la land”. It’s not a metaphor. When the contemporary artist looks at ordinary things, they refuse to stay still. Chairs sprout parrots and monkeys through horn-shaped funnels; a snail drifts away in a makeshift hot-air balloon as a hippo gazes upwards; tree branches knot and twist, crawling with leopards, chameleons, blue elephants, and rubber ducks. Her world is one where the rules of reality are forever bent towards play.

That sensibility was there from the beginning. Born in Calcutta in 1993 and raised in Delhi, Yashika remembers the big Semal tree that stood just beyond her home’s boundary wall. She named it Bunny and hosted picnics with it — two plates of chips, two glasses of Coke, bubbles blown into its branches. What might look like fantasy from the outside was, for her, survival: a way of making space for herself when human connection felt precarious. “I always had low self-confidence and felt a lack of acceptance and love,” she says. “Instead, I found comfort in nature. Bunny became my source of connection and enjoyment.”

Yashika Sugandh

But Sugandh’s la la land isn’t simply innocent. Look again at the works: the colours are hyper-saturated, candy-box bright, but stare long enough and they begin to sour. Smiles stretch too wide, eyes bulge, sweetness tips into something faintly grotesque. The works lure us in with childlike charm only to reveal something stranger, darker.

Sukoon

Why her wonderland matters

When her exhibition Vartaman (Hindi for “the present”) is introduced to the public, the curatorial note describes her “profound reverence for nature” and the “nurturing essence of trees”. It is sincere, no doubt, but these lines flatten her work into moral instruction, turning trees into metaphors of virtue and birds into bullet points for duty. The life of the work slips away beneath the weight of “reverence” and “responsibility.”

The frailty of such language is that it reflects how uncomfortable we’ve become with play itself. We demand depth in the form of lessons, and moral payoff in place of imagination. But whimsy, as Sugandh reminds us, can be serious work — it shows us the irrational, the grotesque, and the joyful instincts that make us human. To treat it as childish is to forget that fantasy is one of our oldest ways of thinking.

Can I grow back again?

Jamun (clock)

Her meticulous brushwork borrows from Indian miniature painting — the same patience and density of detail, but turned towards a far stranger cosmos. “Yashika’s practice dreams in terms of ecology, yet is significantly rooted in our contemporary times,” says curator Sanya Malik. “Her hybrid creatures suggest a cohesion between humanity and nature. In the fast-paced environment we now live in, her practice allows us to slow down, and to acknowledge our encroachment on nature.”

Sanya Malik

Shifting the frame

That word ecology, brings us to what makes her work relevant far beyond aesthetic delight. The Anthropocene — a term coined by scientists to describe our current epoch — is the age in which human activity has reshaped the planet’s climate, soil, and biodiversity more than any natural force. Most conversation around it centres on human guilt and responsibility. But that framing, too, keeps humans at the centre.

Vartaman does the opposite. It doesn’t sermonise about our place in nature; it dissolves the very notion of a “place.” Her animals, objects, and hybrids coexist as equals, part of an ecosystem indifferent to human importance. As Malik puts it, Yashika’s works “help us value life in a meaningful way” precisely because they remove us from the centre of it. In doing so, they offer a quiet corrective to the Anthropocene’s ego — the assumption that we are the planet’s protagonists. Her world reminds us that we are merely one of its unruly species, neither saviours nor villains, but participants in its chaos.

A piece of me is now yours

Garmi ki chutti (Pankha)

Think about how we describe men when they’re odd: “mad genius,” “quirky visionary,” “difficult but brilliant,” “absent-minded professor.” Their strangeness becomes legend. Women, on the other hand, are called “crazy,” “hysterical,” “unstable,” “frivolous,” even “witch.” The same quirks that earn men cult status have long been used to diminish women.

Which is why Sugandh’s wonderland matters. It refuses apology. It doesn’t try to make strangeness respectable or decoration profound. It simply insists that imagination — especially women’s imagination — doesn’t need to be tamed to be meaningful.

Vartaman is on till October 31 at Black Cube Gallery, New Delhi.

Published – October 11, 2025 07:07 am IST