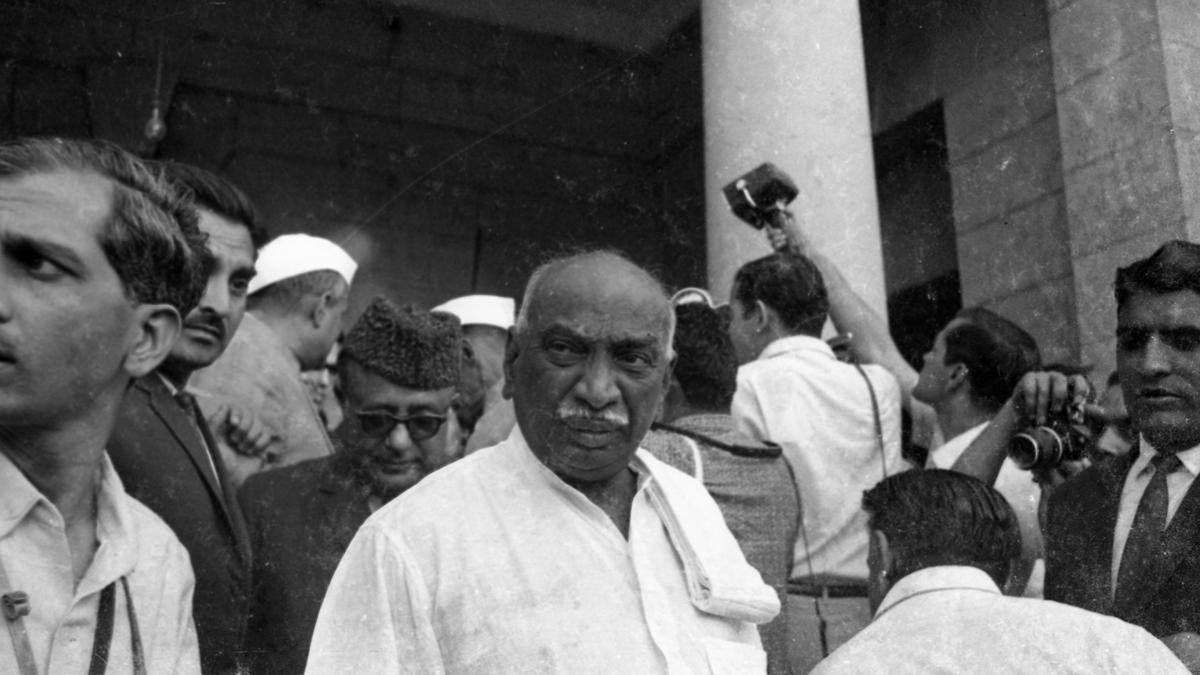

Former Chief Minister K. Kamaraj (1903-75), 122nd whose birth anniversary was celebrated on July 15, 2025 was known for organisational skills as well as fortifying the Congress in Tamil Nadu.

In his long career, he had shepherded the national party in the State so ably that the Congress won most of the electoral battles since 1946. Of course, in 1967 and 1971 Assembly polls, the limits of Kamaraj’s leadership qualities and electoral judgement came to the fore.

There were, however, two electoral contests – bye-elections to the Gudiyatham Assembly constituency in 1954 and to the Nagercoil (now called Kanniyakumari) Lok Sabha seat in 1969 – wherein he was a principal player and on both occasions, he achieved success with finesse. The two bye-elections had one common feature: both were held in regions outside his native district – Ramanathapuram, under which Virudhunagar [the place of his birth] fell between 1910 and 1985.

Gudiyatham Assembly constituency

The need for contesting in the Gudiyatham bye-election arose for Kamaraj as he had to become a member of the legislature following his appointment as Chief Minister in April 1954. Even though the legislature of Tamil Nadu was bi-cameral then, Kamaraj did not choose to become a member of the Upper House (Legislative Council) unlike his predecessor C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji or CR) did in 1952. One of his successors C.N. Annadurai (CNA) used CR’s path in 1967. Also, there was a controversy over the way Rajaji became a Member of the Legislative Council P. Ramamurti, the Marxist theoretician and then in the undivided Communist Party of India (CPI), had unsuccessfully challenged CR’s nomination in the Madras High Court.

Kamaraj, who hailed from Virudhunagar in the southern belt of the State, was a Member of Parliament at the time of becoming the Chief Minister. The vacancy in the Legislative Assembly had existed only for Gudiyatham, which was part of the erstwhile North Arcot district (now split into Vellore, Ranipet, Thirupathur and Tiruvannamalai districts). At that time, Gudiyatham was a double-member constituency with one seat reserved for Scheduled Castes (SC).

While Kamaraj, in June 1954, made it clear to the party that he would like to enter the fray for the general seat, the Scheduled Castes’ Federation (SCF), established by B.R. Ambedkar, had approached him with a request to let the Congress adopt its member for the reserved seat, according to a report of The Hindu on June 22, 1954. The report had even mentioned that [in the event of the request being accepted,] “this will be the first time” for the Congress and the SCF to have an electoral understanding. However, this proposal did not fructify, possibly due to the tense ties between Ambedkar and the Congress at the all-India level. Eventually, the SCF was left to put up its own candidate in Gudiyatham. For the reserved seat, the Congress’ nominee was T. Manavalan and the Federation’s, M. Krishnaswami.

Even though the Congress’ candidate was the Chief Minister himself, the ruling party did not take chances. Two Central Ministers – Maragatham Chandrasekhar, who was Deputy Minister for Health, and T.T. Krishnamachari (TTK), Union Minister for Industry and Commerce – were drafted for the poll work, apart from C. Subramaniam, ranked no. 2 in the Kamaraj Cabinet and Finance Minister.

The Chief Minister’s principal rival was K. Kothandaraman of the CPI. Veteran journalist T.S. Chockalingam, in his biography of the former Chief Minister, mentions that members of the Congress all over the State had “turned their attention” towards Gudiyatham and “friends” from every district had begun their campaign for Kamaraj. There was “one more miracle” – the Dravidar Kazhagam and the Muslim League declaring publicly their support for him and commencing their canvassing.

Also Read | When BJP talks of Kamaraj rule…

Kamaraj was not one who would get carried away by “such widespread support.” He plunged himself in the campaign and carried out his work in villages. With a few weeks to go for the date of polling, he had covered 100 out of 160 villages in the constituency, The Hindu wrote on July 18, 1954. Responding to the criticism of the Communists that the Congress, despite being in power at the Centre and in States, had not resolved many problems of the country, Kamaraj, at a meeting in Cherlapalli, wondered how “age-long difficulties” of people could be removed within seven years of the country gaining Independence. Krishnamachari told the voters that Kamaraj was the “friend and follower” of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Being a person conscious of the living standards of the poor, he would “do his best” to raise them, TTK assured the voters.

When the result was out on August 4, 1954, it was on expected lines. Kamaraj had defeated the CPI’s candidate by a comfortable margin – about 38,000 votes. That was the only occasion when the former Chief Minister was a candidate in the northern region of the State.

Nearly 15 years later, the political field in the State was not that benign either to Kamaraj or to the Congress. In early 1967, the national party was dislodged from power in the State nearly after a 20-year-long rule. Kamaraj himself lost in the Virudhunagar assembly constituency to a lightweight of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). Spearheaded by CNA, the DMK, which had stitched a rainbow coalition comprising the Swatantara and the CPI (Marxist), had captured power in a stunning fashion. At the Centre, though the Congress was in power, there had been changes in the balance of power. The “old guard” in the ruling party was experiencing the phase of decline and naturally, there had been reports of difference between the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and some of her Cabinet colleagues, who were considered members of the “old guard.” As the Congress’ pre-eminent position in the country’s politics had started waning, new political forces were emerging.

Nagercoil Lok Sabha constituency

The death of ‘Marshal’ A. Nesamony had necessitated the bye-election to the Nagercoil Lok Sabha constituency. Kamaraj, who was looking for an opportunity to regain people’s confidence after the Virudhunagar defeat, announced his candidature on December 1, 1968, this newspaper reported the next day. There were six other contestants. But, the battle was between him and M. Mathias, who was backed by the DMK-led alliance that included the Swatantara and the Muslim League.

Ordinarily, Nagercoil should not have been difficult terrain for the Congress, which had a strong base even then, as is now. Besides, even in 1967, when the national party was thrashed in most of the districts, five out of six assembly constituencies, which formed Nagercoil, went in favour of the Congress. But, it was the DMK, which had decided to make the contest more intense.

Former Congress leader Pazha Nedumaran, in his “Perunthalaivarin Nizhalil” [In the shadow of great leader (meaning Kamaraj)], stated that the bye-election had been turned into another “Kurukshetra War,” the entire credit for which should go to the then Public Works Minister M. Karunanidhi and former Assembly Speaker Si. Pa. Aditanar, who later became a Minister in the DMK Cabinet headed by Karunanidhi. In the assessment of Mr Nedumaran, the DMK leaders had entertained the notion that if Kamaraj had tasted defeat [the possibility of which could not be ignored especially after Virudhunagar], he could be driven out of the politics of Tamil Nadu.

With the election fever mounting, the atmosphere was “getting surcharged” with a stream of lorries bringing supporters of rival parties from outside the district, The Hindu wrote on January 5, 1969, three days before the date of polling. “In the last 10 days, the Police have arrested about 200 persons, most of them Congressmen in connection with election clashes,” the newspaper reported. The then Tamil Nadu Congress Committee (TNCC) chief, C.Subramaniam (CS), accused the DMK of bringing in “hired hooligans” from the neighbouring Tiruneveli district. Karunanidhi, who had overseen the campaign of Mathias, challenged CS’s allegations and put the blame on the Congress, which, he said, was “indulging in violence.” As for the complaint regarding the involvement of senior DMK Ministers in the campaign, Karunanidhi reasoned his party was “only following the example” set by the Congress. Kamaraj’s response was his party had refrained from inviting Union Ministers to campaign in the constituency, even though they were “ready to come.”

The bye-election frenzy rose to the boiling point on the midnight of January 4 when a worker of the DMK, Kittu, was killed and two others suffered stab injuries. That day, the head of the State police (which was called Inspector General) R.M. Mahadevan reached Nagercoil to oversee the preparations. The Superintendent of Police S. Dayasankar chose to go on medical leave for a month. He was immediately replaced by K. Srikumara Menon, Deputy Commissioner, Traffic. Madurai. On the day of polling (January 8), the then Chief Election Commissioner, S.P. Sen Verma, himself visited as many as 35 polling stations of the constituency, according to this newspaper. Given the high-decibel campaign, the voter turnout exceeded 75%, a few percentage points higher than what Nagercoil recorded in 1967.

There was no element of great surprise in the result. Kamaraj won the bye-election by a huge margin of 1,28,201 votes over Mathias, by polling 2,49,437 votes.

Commenting on the former Chief Minister’s electoral battles, A. Gopanna, who had also authored his biography, feels Kamaraj always attached greater emphasis on drawing support from the people directly than anything else. R. Kannan, a biographer of former Chief Ministers C.N. Annadurai and M.G. Ramachandran apart from writing ‘The DMK Years’, says Kamaraj, by contesting in Nagercoil, had “wanted to stay relevant.”

Kamaraj’s participation in the two bye-elections had only shown how much importance he, as a political leader, had paid to securing legitimacy from the public.