In a city as digitally connected as Delhi, navigating the online world comes with myriad challenges. While the benefits of digital payments, social media, and internet banking are evident, they are paralleled by increasing incidents of cybercrime. Cybercrime has become one of the most critical and pressing concerns across India over the past couple of years, with Delhi being the hotspot. According to reports, Delhi residents lost over ₹700 crore in 2024 to cybercrime. Despite the intensity and seriousness of the issue, structural gaps continue to exist. For example, under the Information Technology Act, 2000 only officers (not below the rank of an inspector) can investigate cybercrime, yet most cyber police stations lack the needed number of officers for the same purpose. This comprehensive study conducted by the Lokniti-CSDS sheds light on Delhi’s cyber landscape through three critical lenses — public awareness; personal experience with cybercrime; and the efficiency of reporting and redressal systems.

Awareness about digital crimes

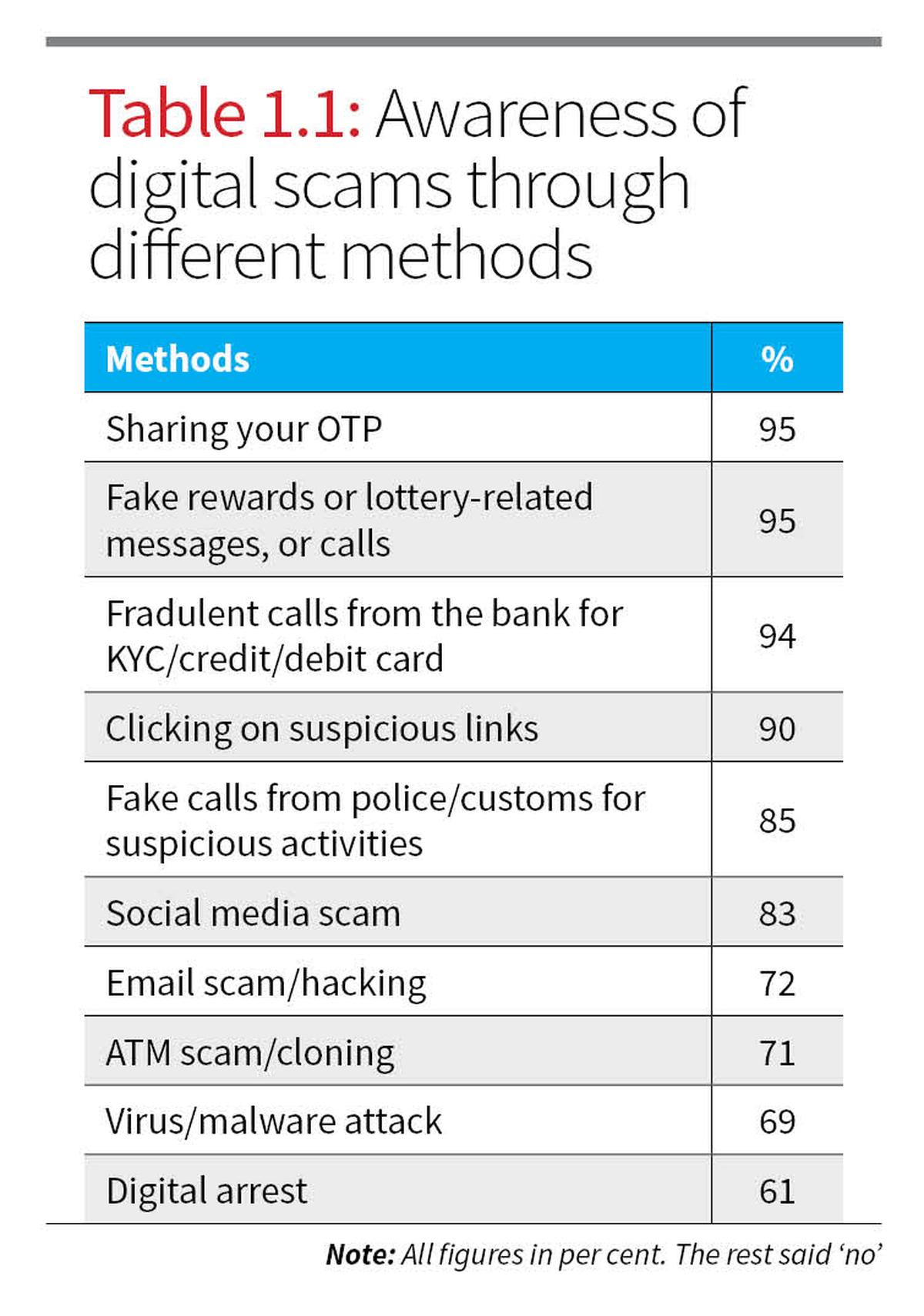

Public awareness about the different types of digital fraud is encouragingly high. As Table 1.1 reveals, more than 90% of Delhi residents are aware of cybercrime methods such as sharing One Time Passwords (OTPs), fake reward calls, and fraudulent banking requests. Interestingly, awareness drops for newer scams like ‘digital arrest’, known to only 61% of respondents. This shows that while traditional scams are well recognised, there remains a gap in understanding evolving threats.

93% of respondents in the study knew they could file a complaint if they became a victim of cybercrime.

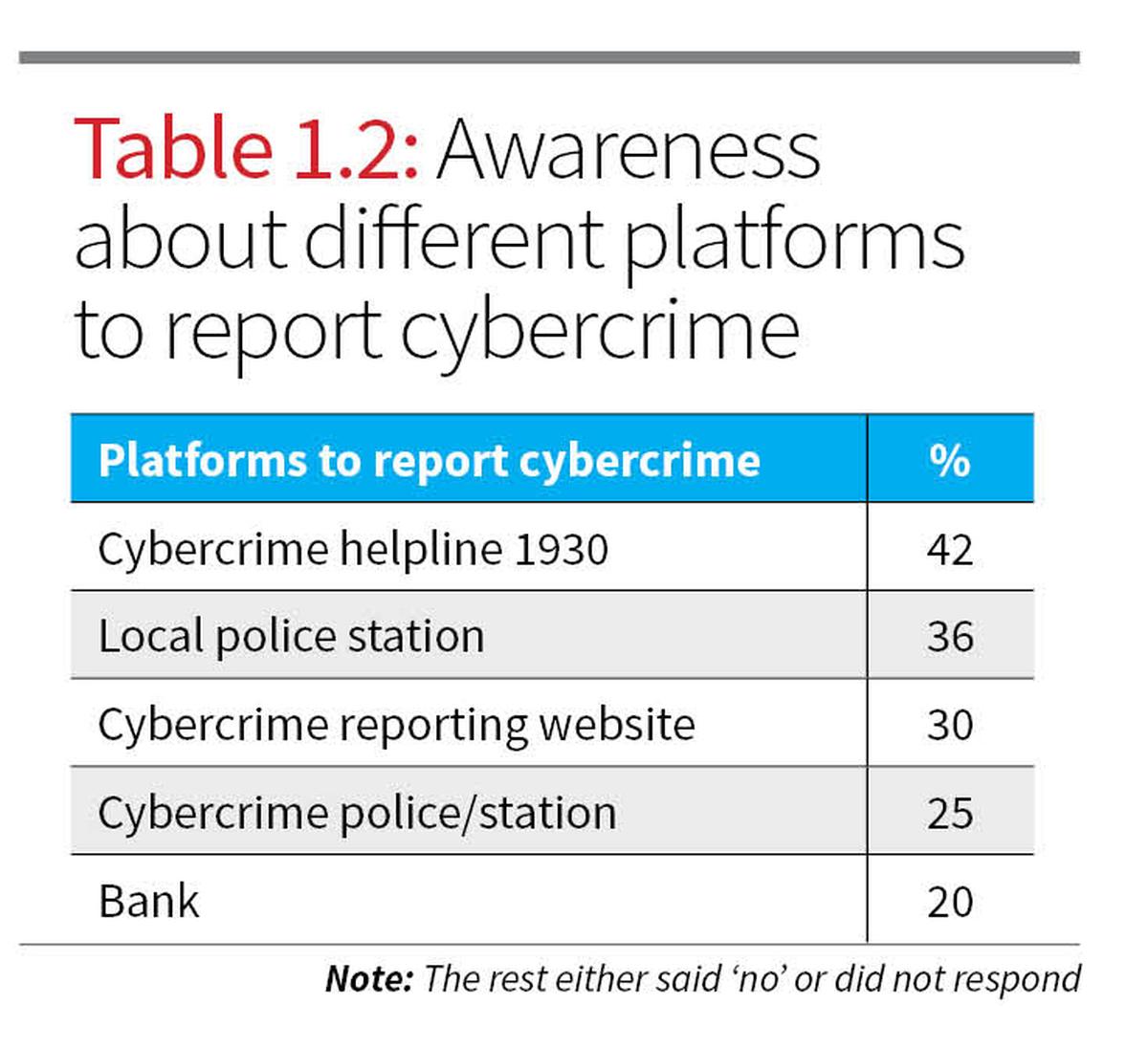

However, Table 1.2 shows that while many knew reporting was possible, only 42% knew of the national cybercrime helpline (1930), with even fewer being aware of cyber police stations (25%) or the reporting website (30%). This reveals a gap between awareness and digital reporting literacy.

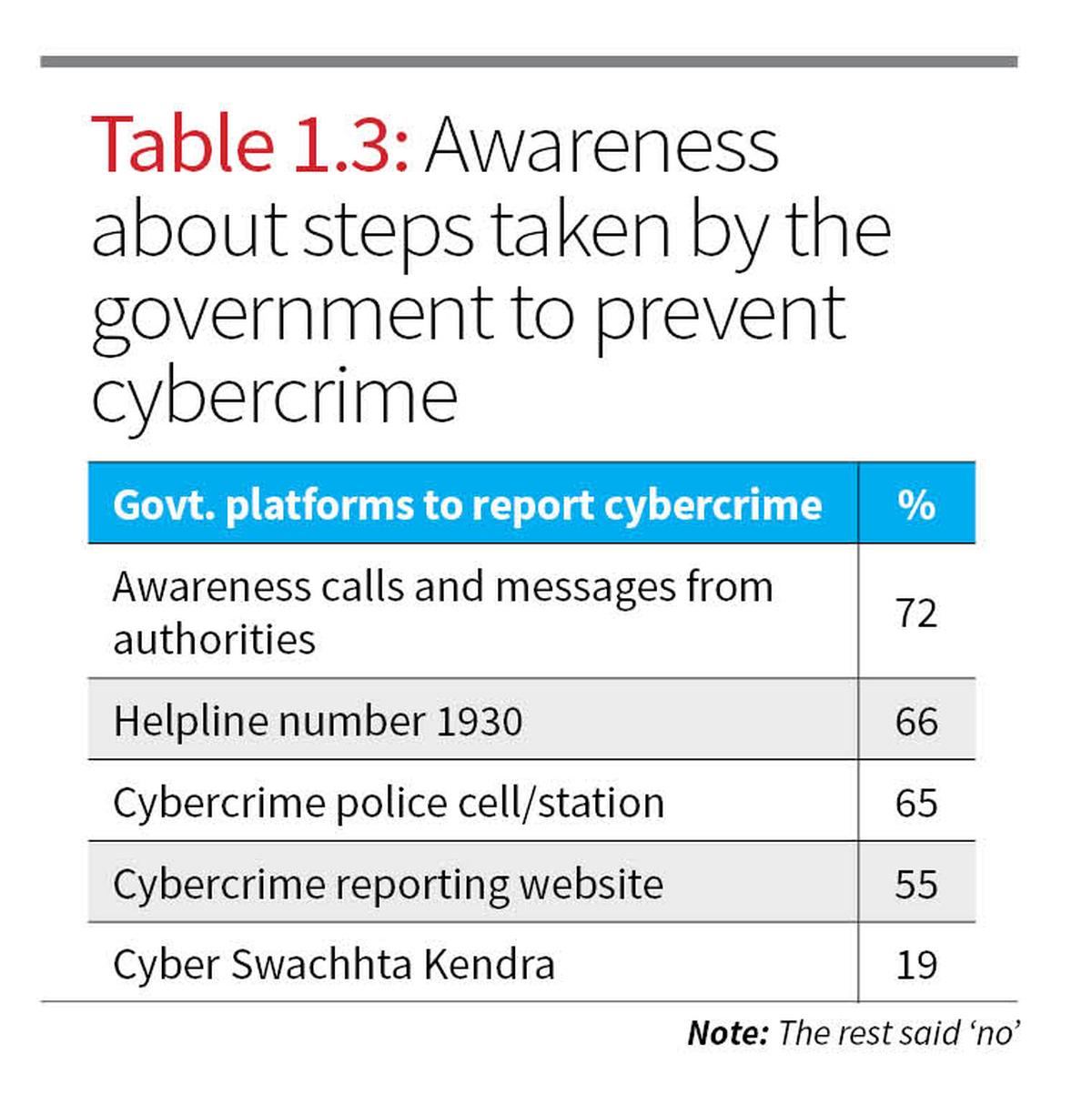

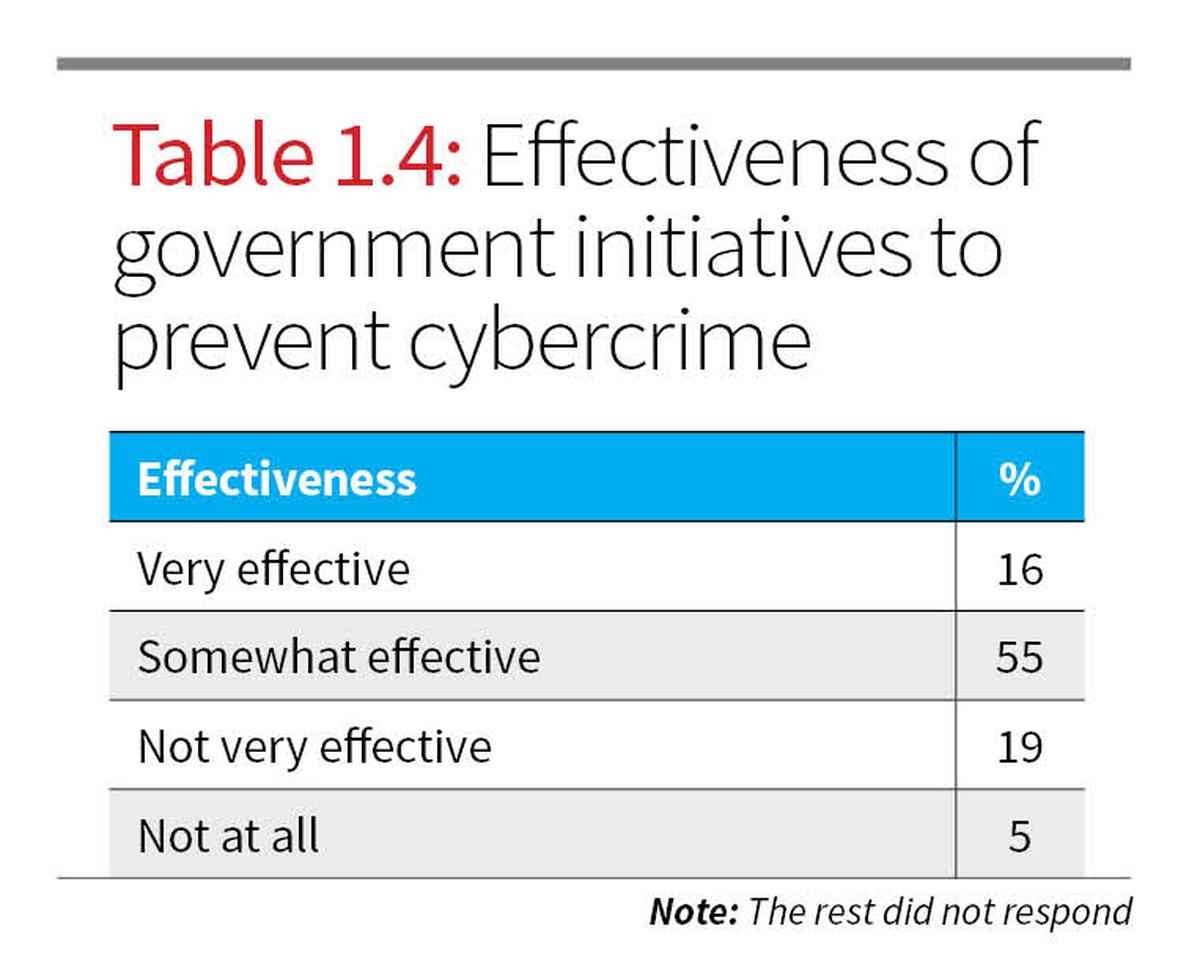

While government-led awareness campaigns, particularly mass messages and calls, were relatively well recognised (72% awareness as per Table 1.3), awareness of more concrete initiatives like the Cyber Swachhta Kendra was low (19%). When asked about the government’s effectiveness in combating cybercrime (Table 1.4), only 16% of people rated it as “very effective”.

Most (55%) found it “somewhat effective,” and nearly one in four saw the efforts as inadequate. While the government’s approach has reached citizens, it has not instilled confidence.

On protection from cyber threats

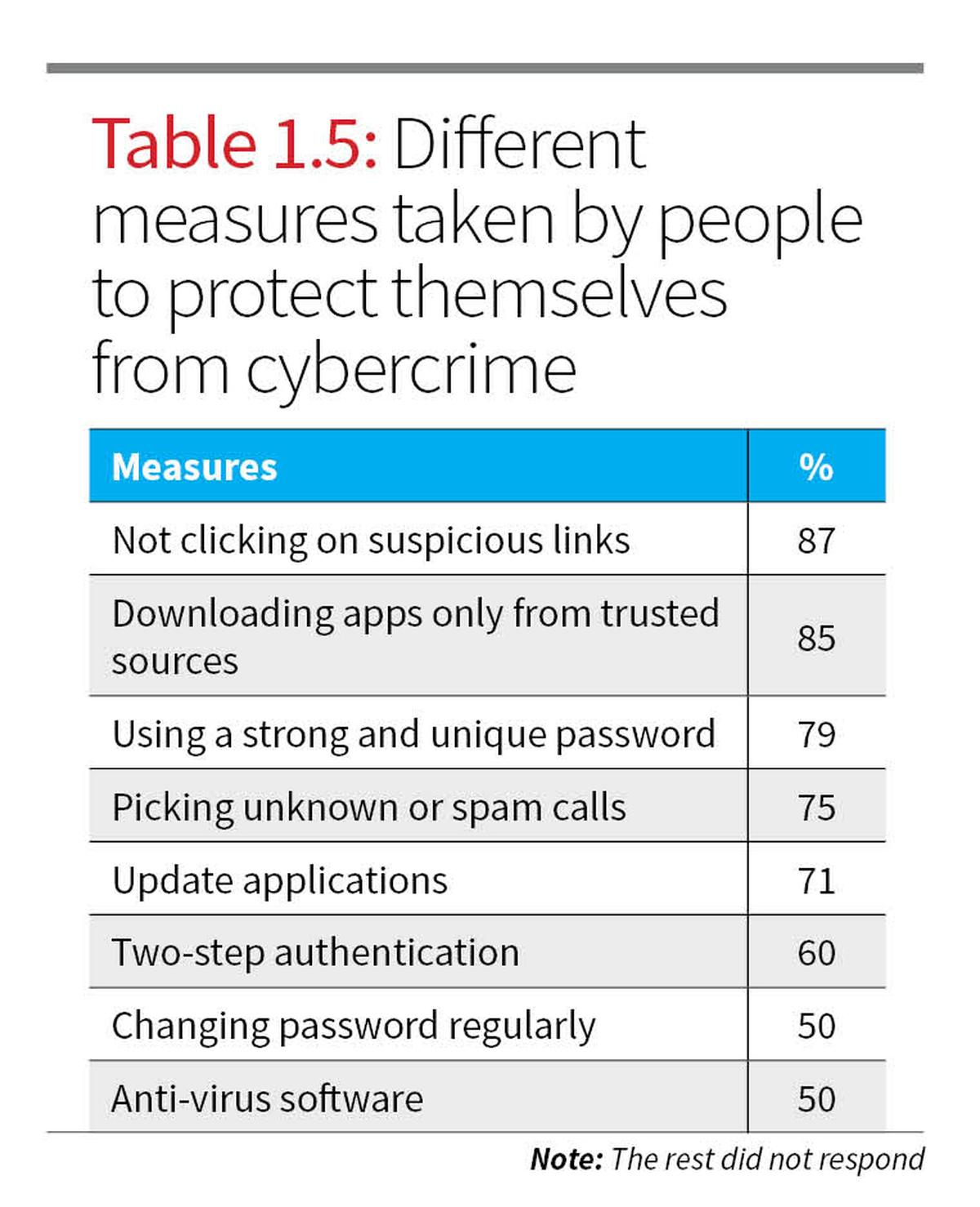

People in Delhi are adopting preventive measures. According to Table 1.5, the majority avoid suspicious links (87%), download apps only from trusted sources (85%), and around 79% use strong passwords.

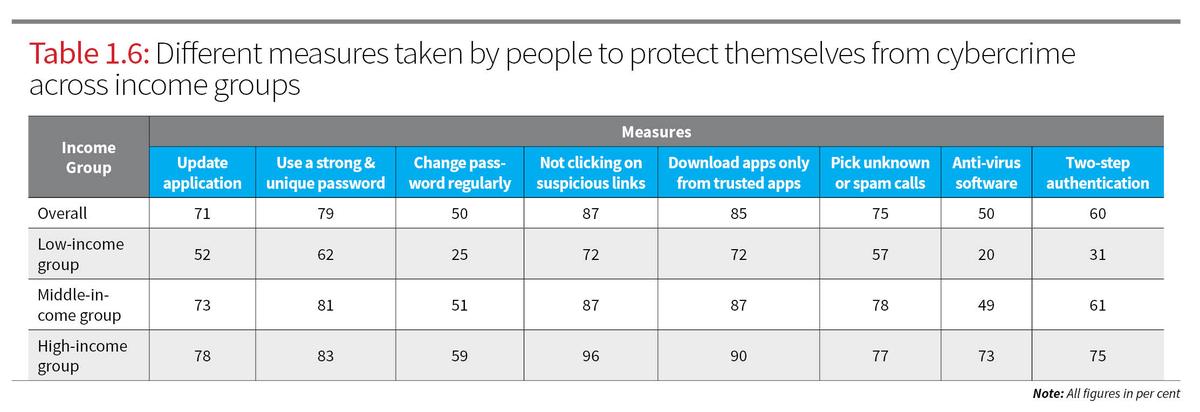

However, more advanced practices such as regularly changing passwords (50%) or using antivirus software (50%) are far less common. The socio-economic digital divide becomes especially apparent in Table 1.6.

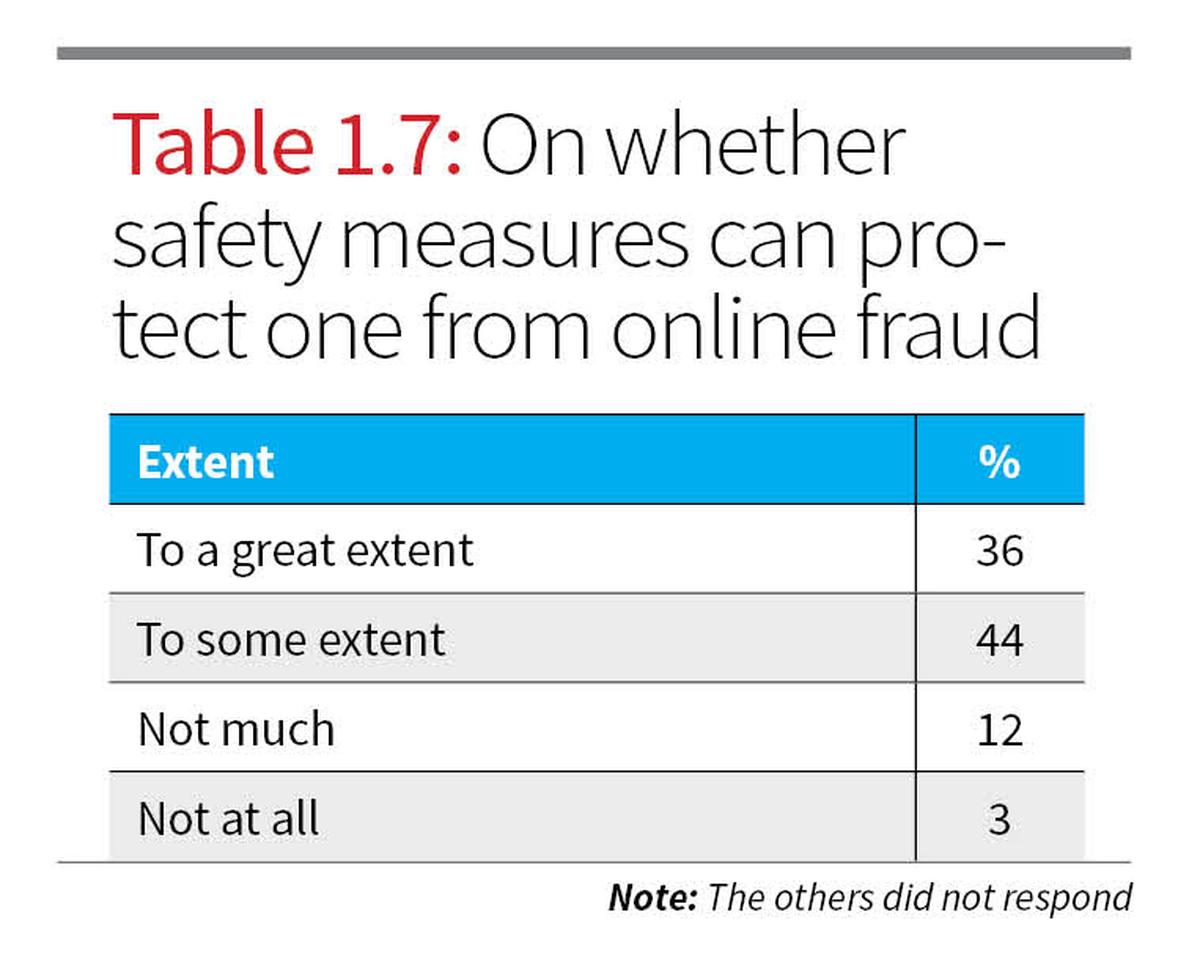

High-income respondents are far more likely to adopt comprehensive security measures, including antivirus software (73%) and two-step authentication (75%), compared to just 20% and 31% in low-income groups respectively. This disparity highlights the intersecting role of digital literacy, affordability, and access to cyber safety. Belief in the effectiveness of these precautions is strong, with 80% believing that these precautions protect them either “to a great extent” or “some extent” (Table 1.7).

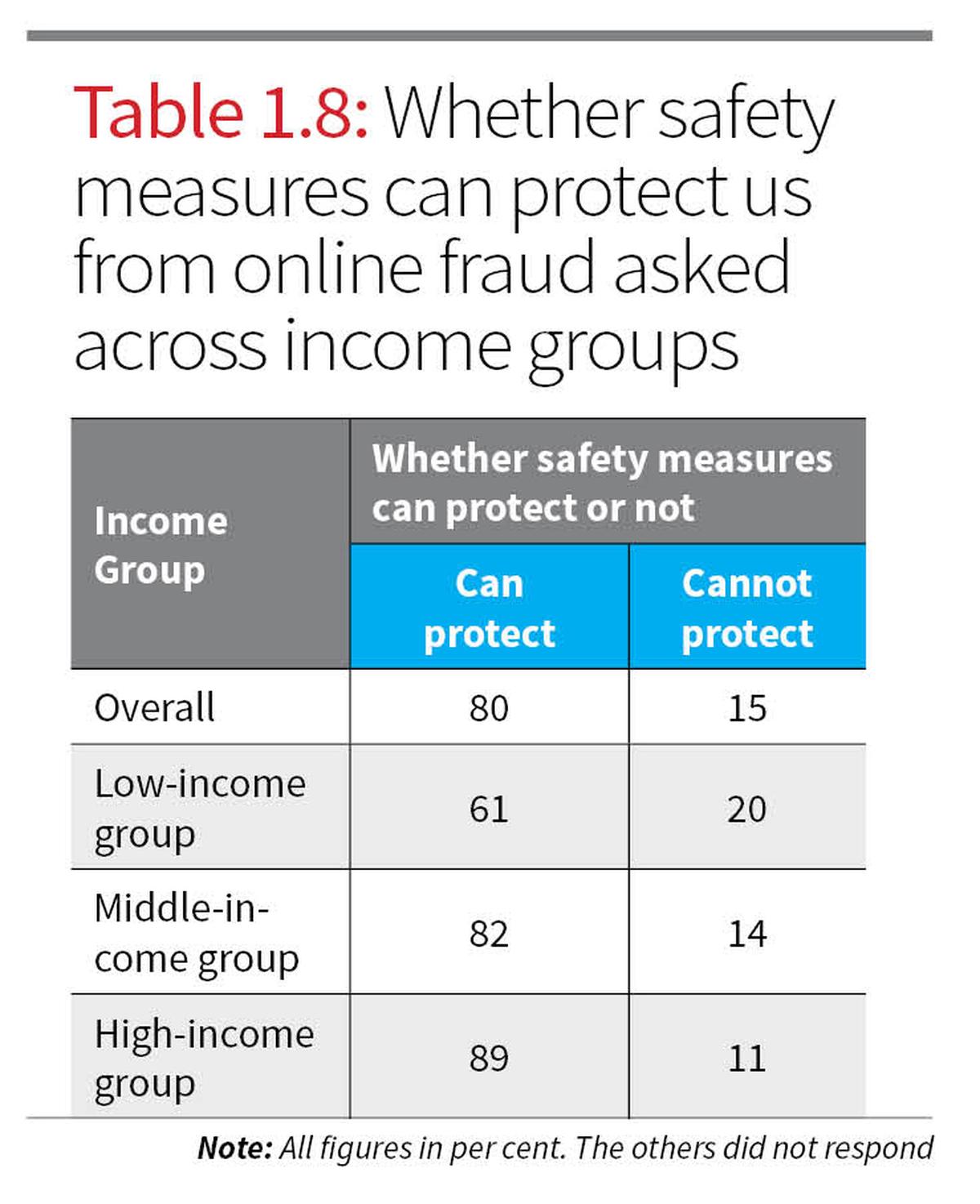

However, as Table 1.8 shows, confidence again varies by income (the columns “great extent,” “some extent,” and “not much,” “not at all” have been merged).

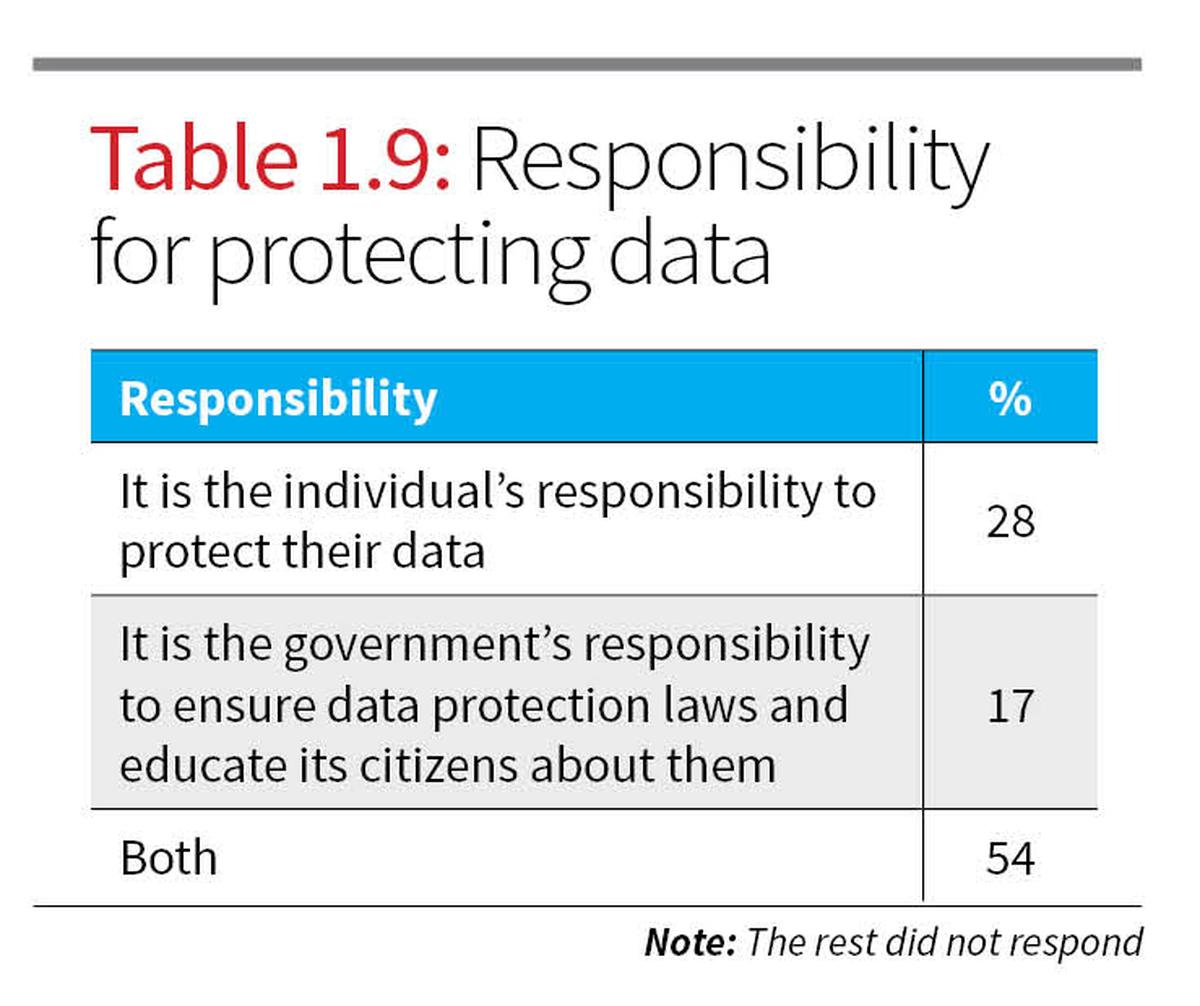

While 89% of high-income respondents trust their protective measures, only 61% of low-income participants share that belief in comparison. This perceived vulnerability may contribute to higher stress levels and avoidance behaviour among vulnerable groups. When asked about responsibility for data protection, more than half of the respondents (54%) said it should be a joint effort between individuals and the government (Table 1.9).

Reporting cybercrime

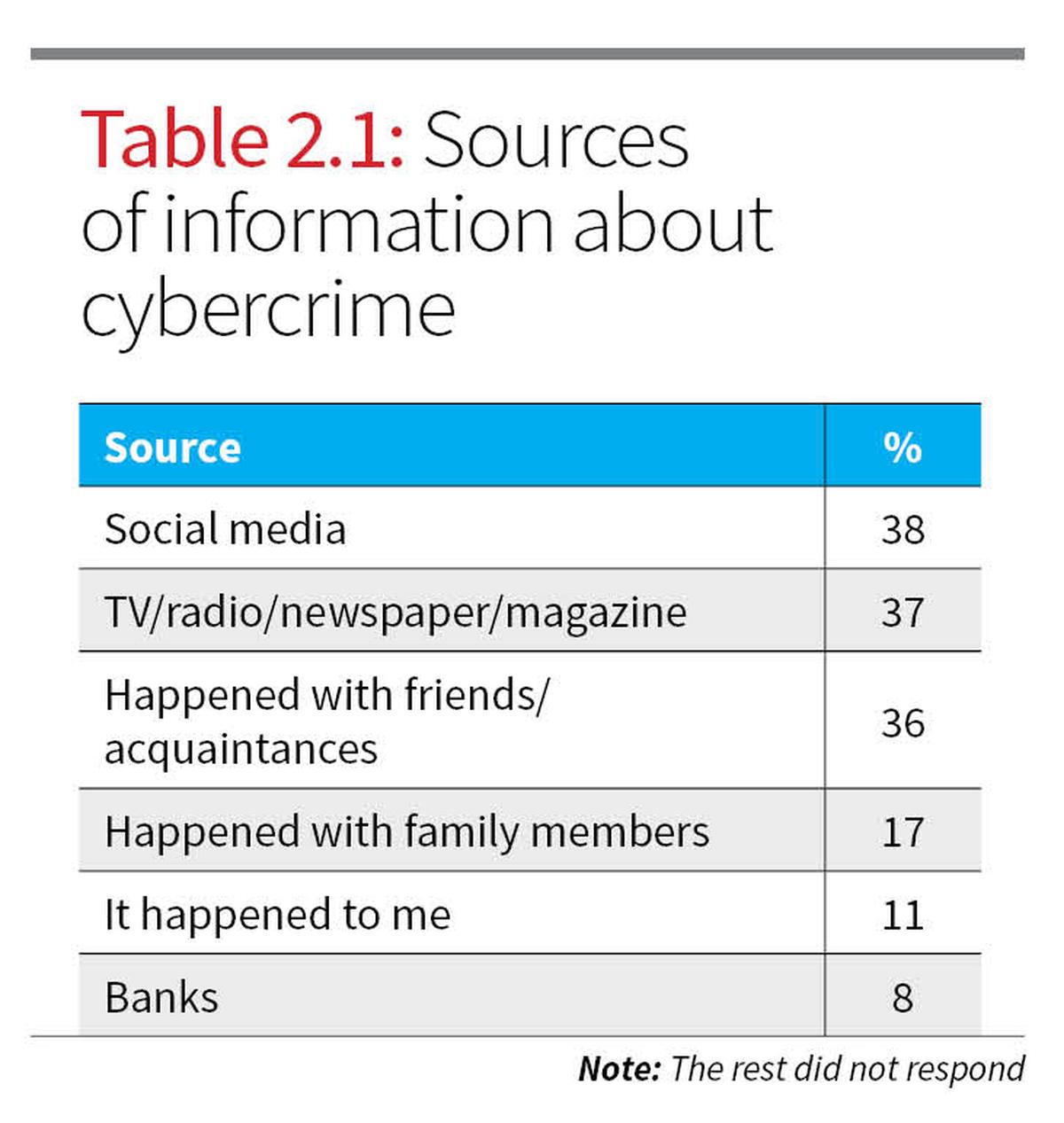

The Lokniti survey reveals that awareness of cybercrime is nearly universal among Delhi’s residents. 96% of respondents stated that they had heard or read about financial frauds and scams online. When asked how they came to know about cybercrime, the majority cited non-institutional sources.

As shown in Table 2.1, 38% became aware through social media, 37% via traditional media, and 36% through personal experiences of friends or acquaintances. Notably, only 8% received information through banks, despite their central role in financial security.

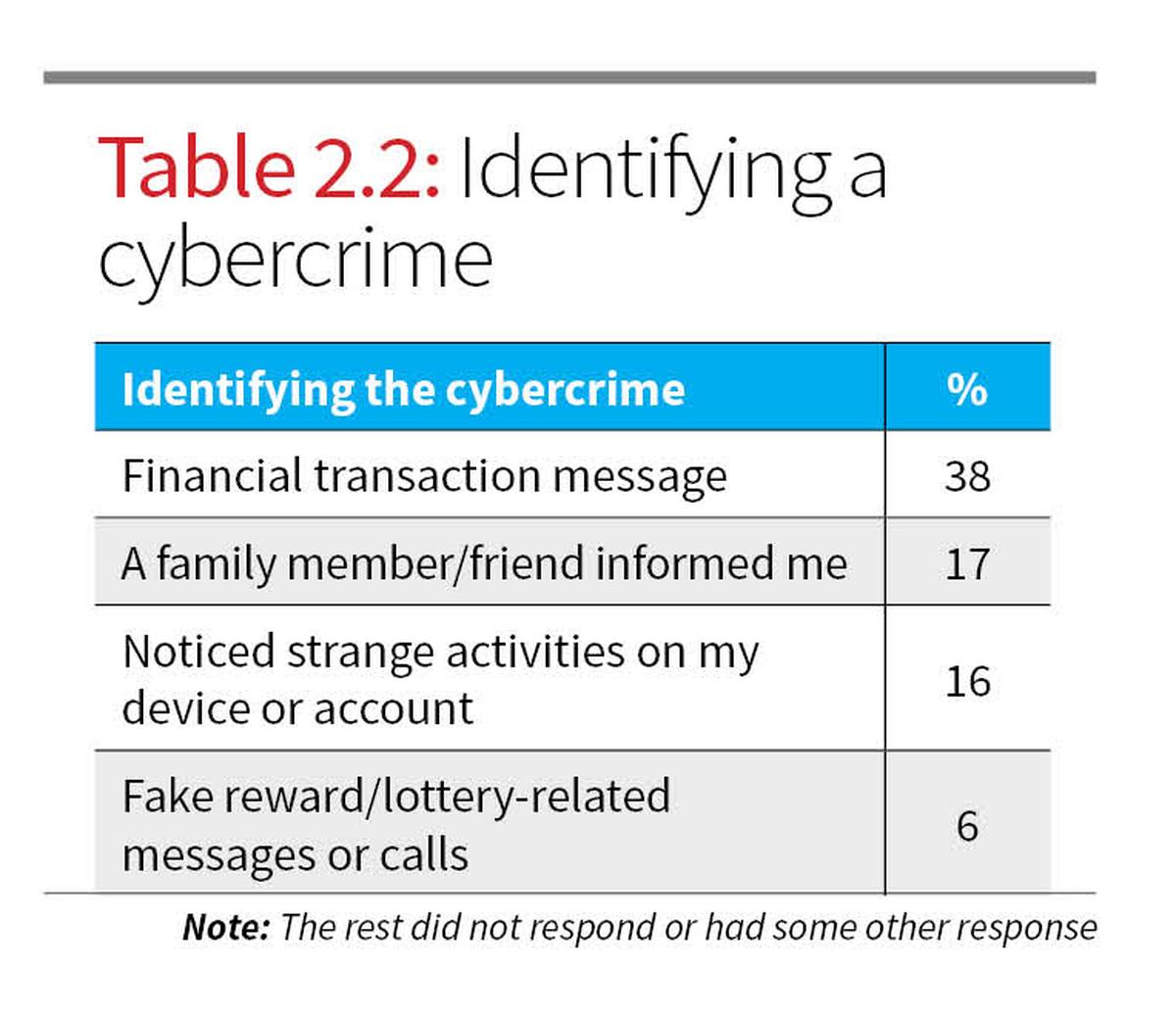

Among those who experienced cybercrime first-hand or through family members, the most common method of identifying the incident was through transaction alerts.

In Table 2.2, 38% reported recognising the fraud upon receiving a financial transaction message. Others were alerted by family or friends (17%) or by noticing irregularities on their account or device (16%). Very few identified the issue due to device malfunction, indicating that non-technical signs were more influential in realising that a cybercrime had occurred.

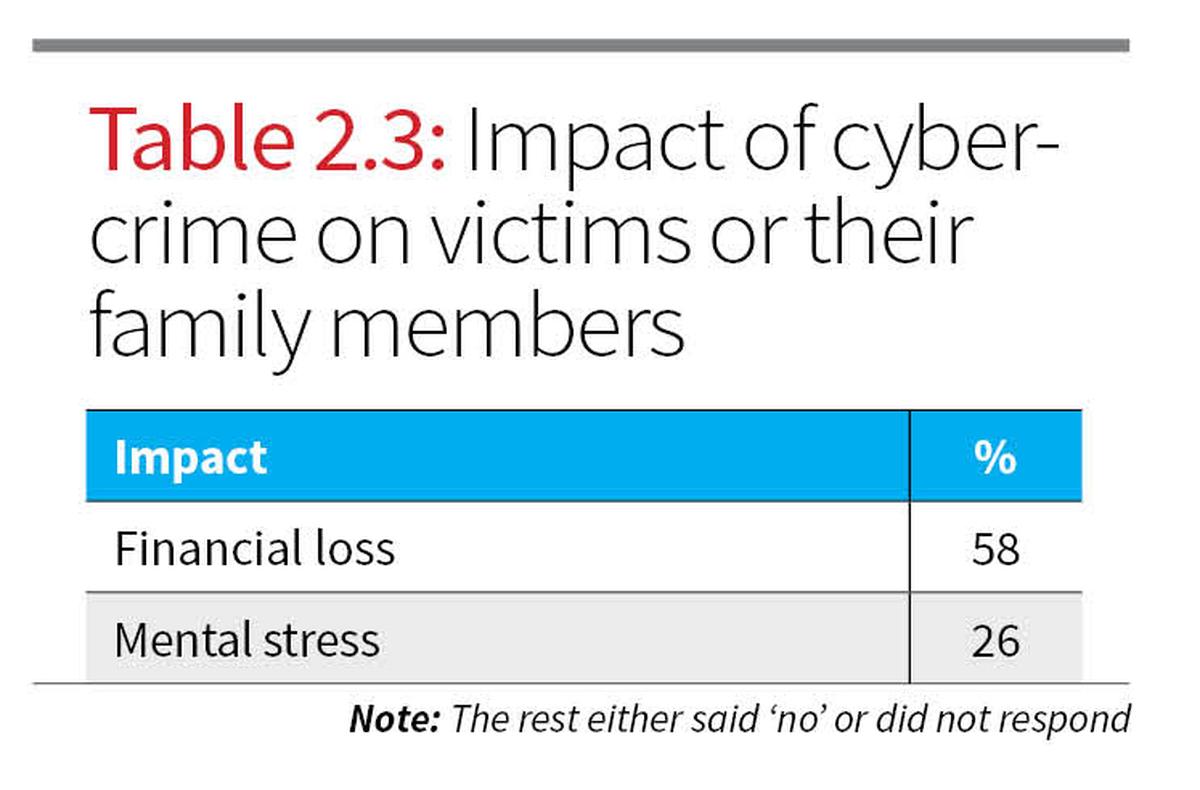

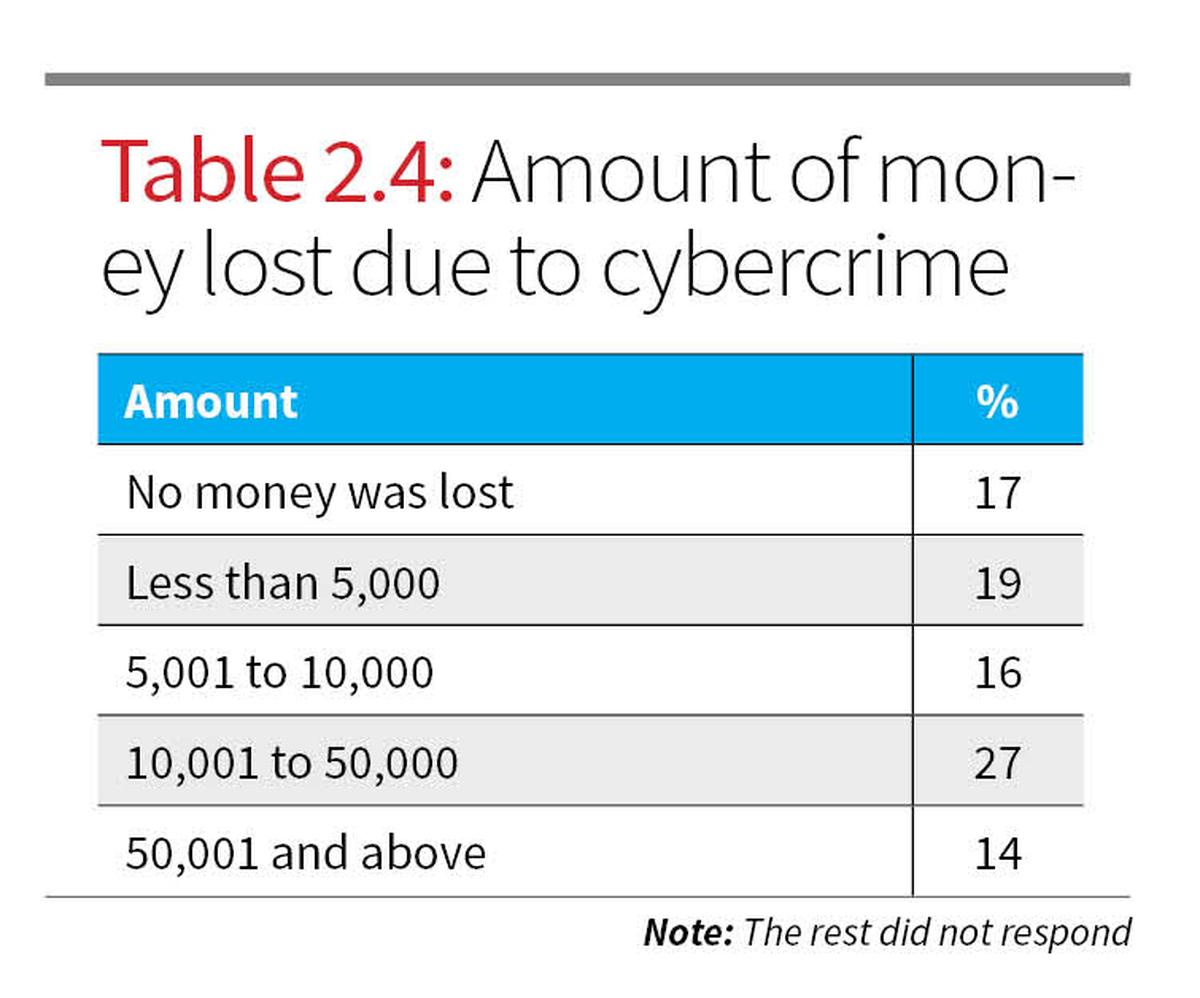

As indicated in Table 2.3, 58% of affected respondents reported financial loss, while 26% experienced mental stress. This suggests that while the economic impact is prominent, the psychological burden is also substantial and requires attention in policy discussions. In terms of the quantum of financial loss, Table 2.4 reveals that 27% of victims lost between ₹10,001 and ₹50,000, while 19% lost amounts less than ₹5,000. 14% of respondents reported that they had lost over ₹50,000 owing to cybercrime.

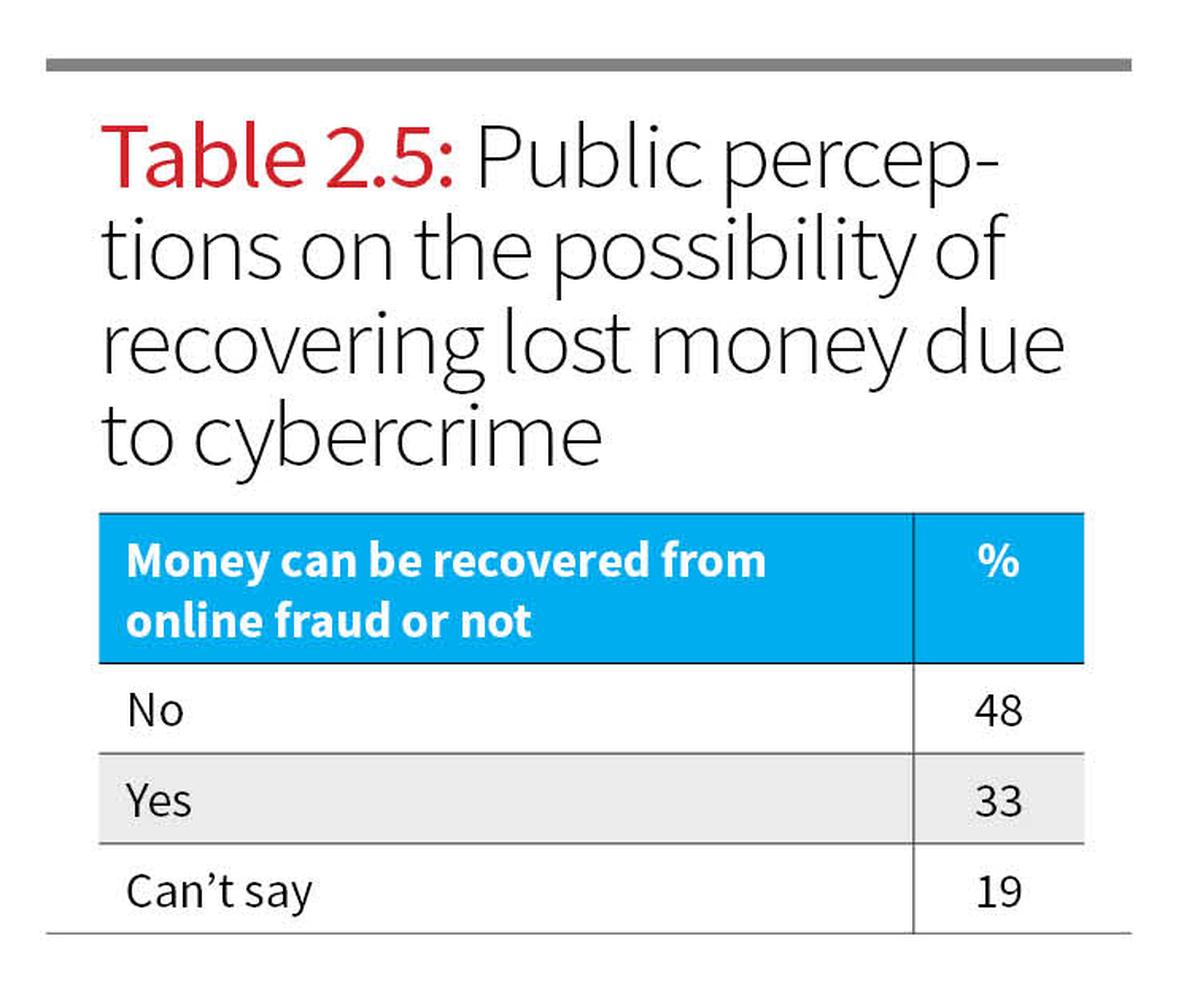

One of the most concerning findings relates to the perceived and actual inefficacy of recovery mechanisms. According to Table 2.5, 48% of respondents believed that money lost to cyber fraud could not be recovered.

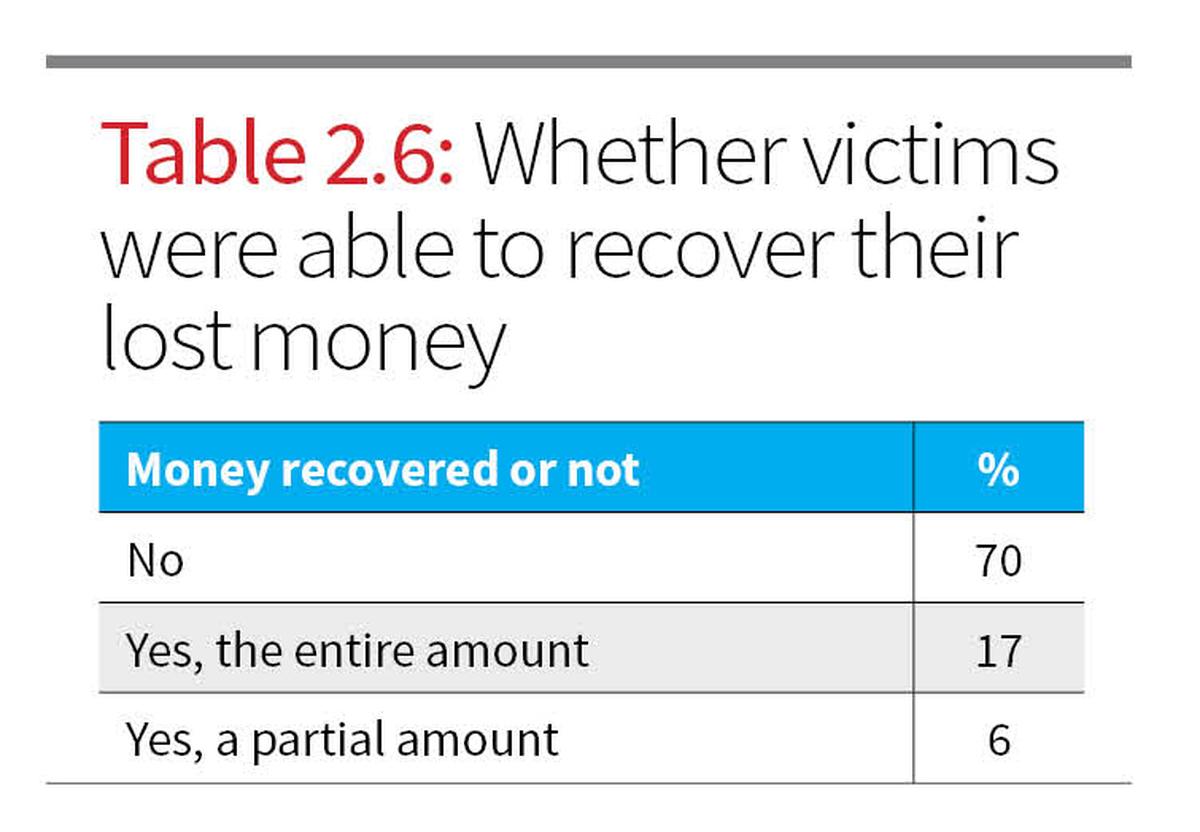

Only 33% believed that recovery was possible. These perceptions are corroborated by data in Table 2.6, which focuses exclusively on victims.

Among those who lost money, 70% reported they did not recover any part of it. Only 17% said the full amount was returned, and 6% reported partial recovery. This highlights the lack of existing institutional mechanisms for financial redressal.

Where does help come from?

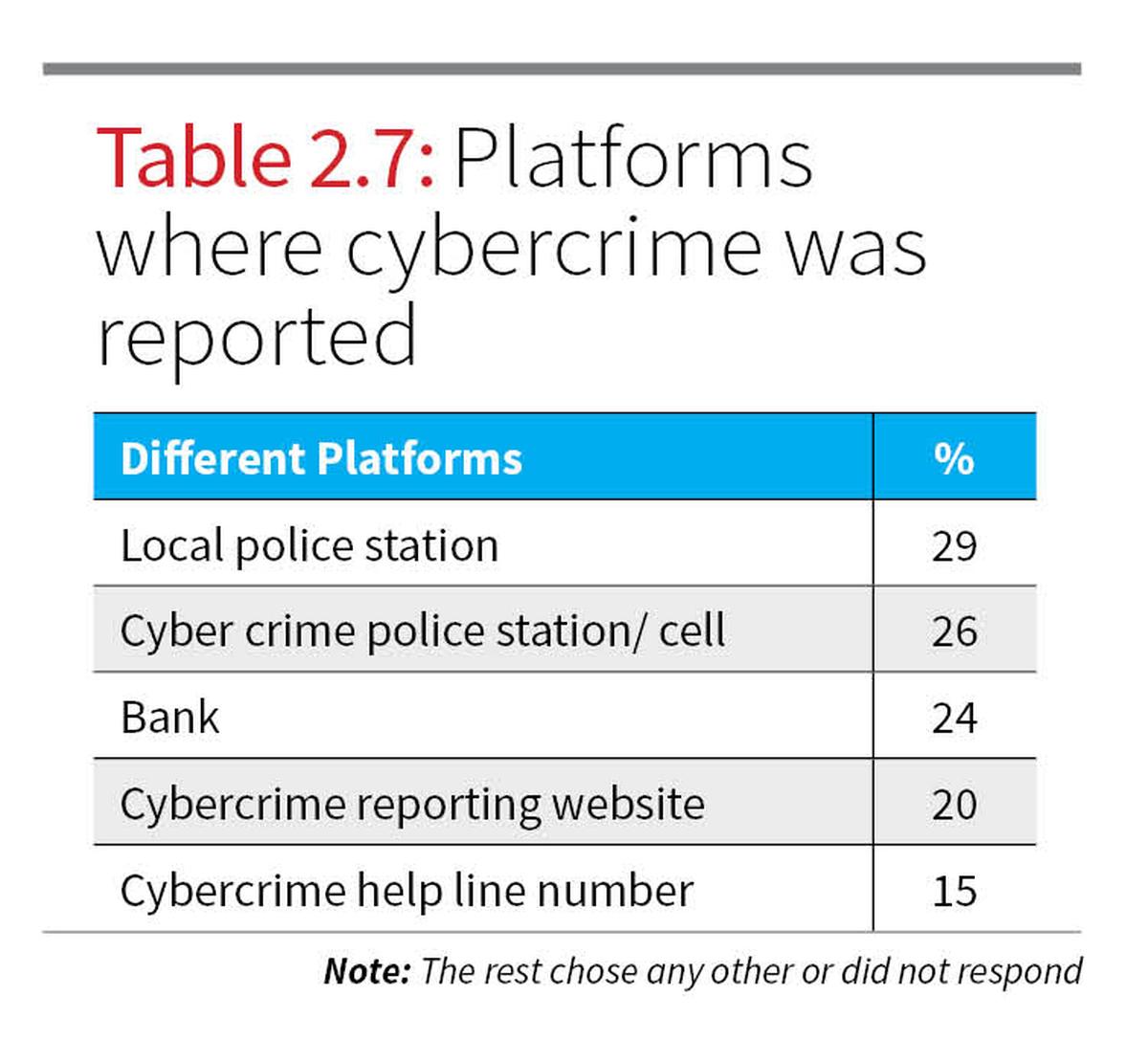

The survey findings indicate a serious gap between the experience of cybercrime and the response received from authorities, marked by high levels of under-reporting and widespread dissatisfaction. Only 21% of respondents who experienced cybercrime reported it, while 76% refrained from taking formal action, pointing to either a lack of awareness or deep mistrust in institutional mechanisms. Among those who did report, traditional platforms were more commonly used, 29% approached local police stations, 26% contacted cybercrime police cells, and 24% reported it to banks, whereas digital platforms like the cybercrime reporting website (20%) and helplines (15%) were less frequently used (Table 2.7), indicating the need for more credible and accessible online systems.

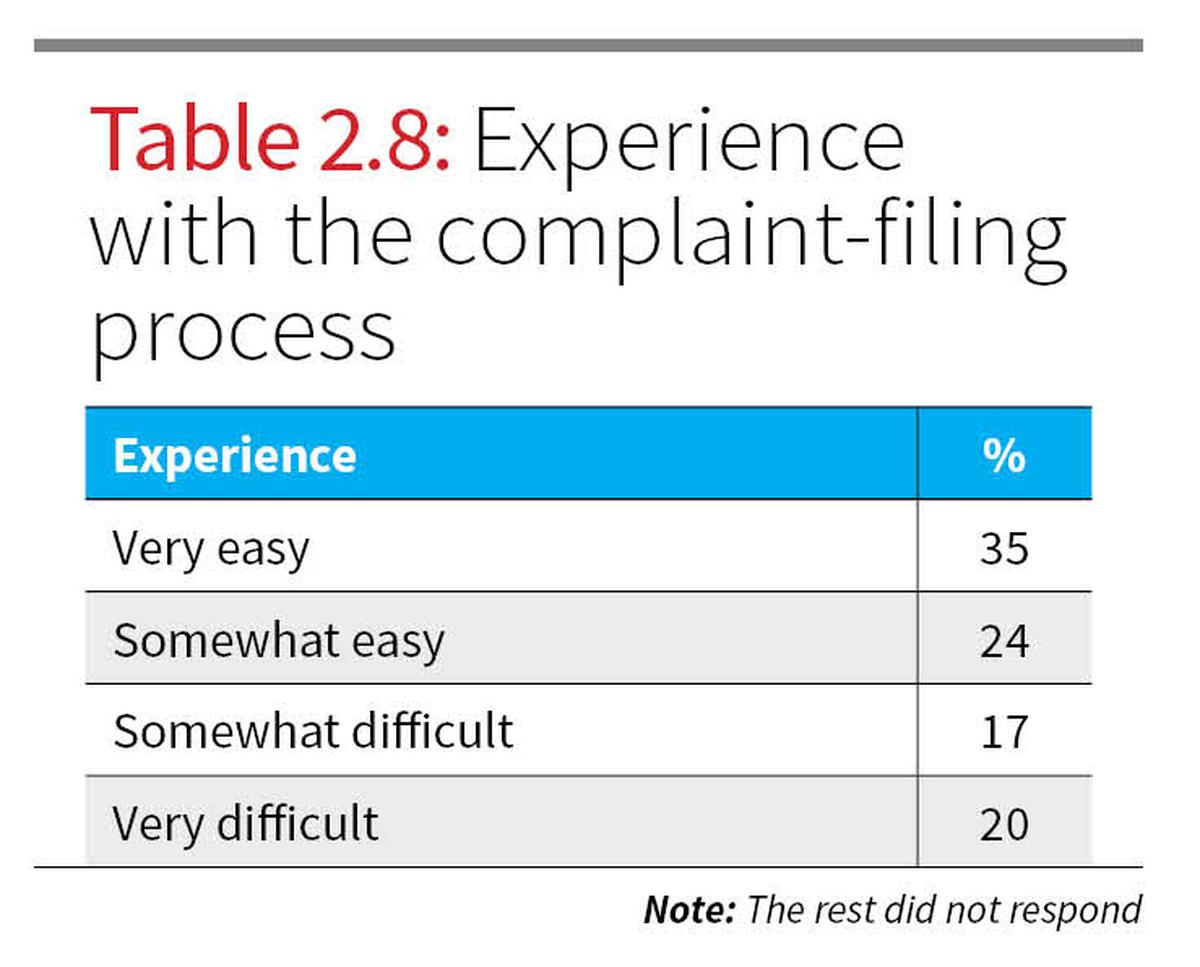

The complaint process itself yielded mixed responses, with 35% finding it “very easy” and 24% “somewhat easy”, but a notable 37% found it difficult to register a complaint (Table 2.8), suggesting procedural difficulties for users.

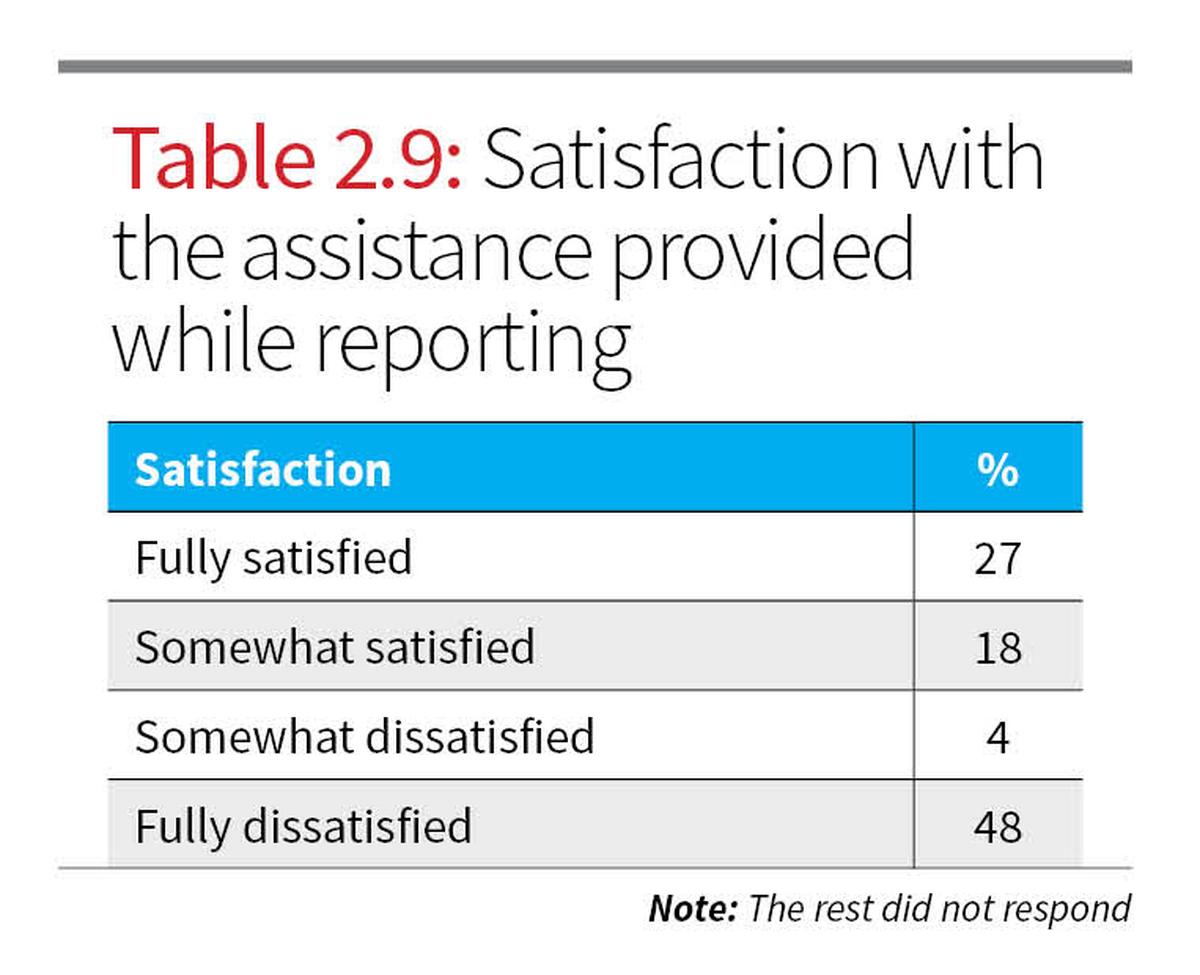

Public satisfaction with institutional support was also low, with 48% being fully dissatisfied and only 27% fully satisfied (Table 2.9).

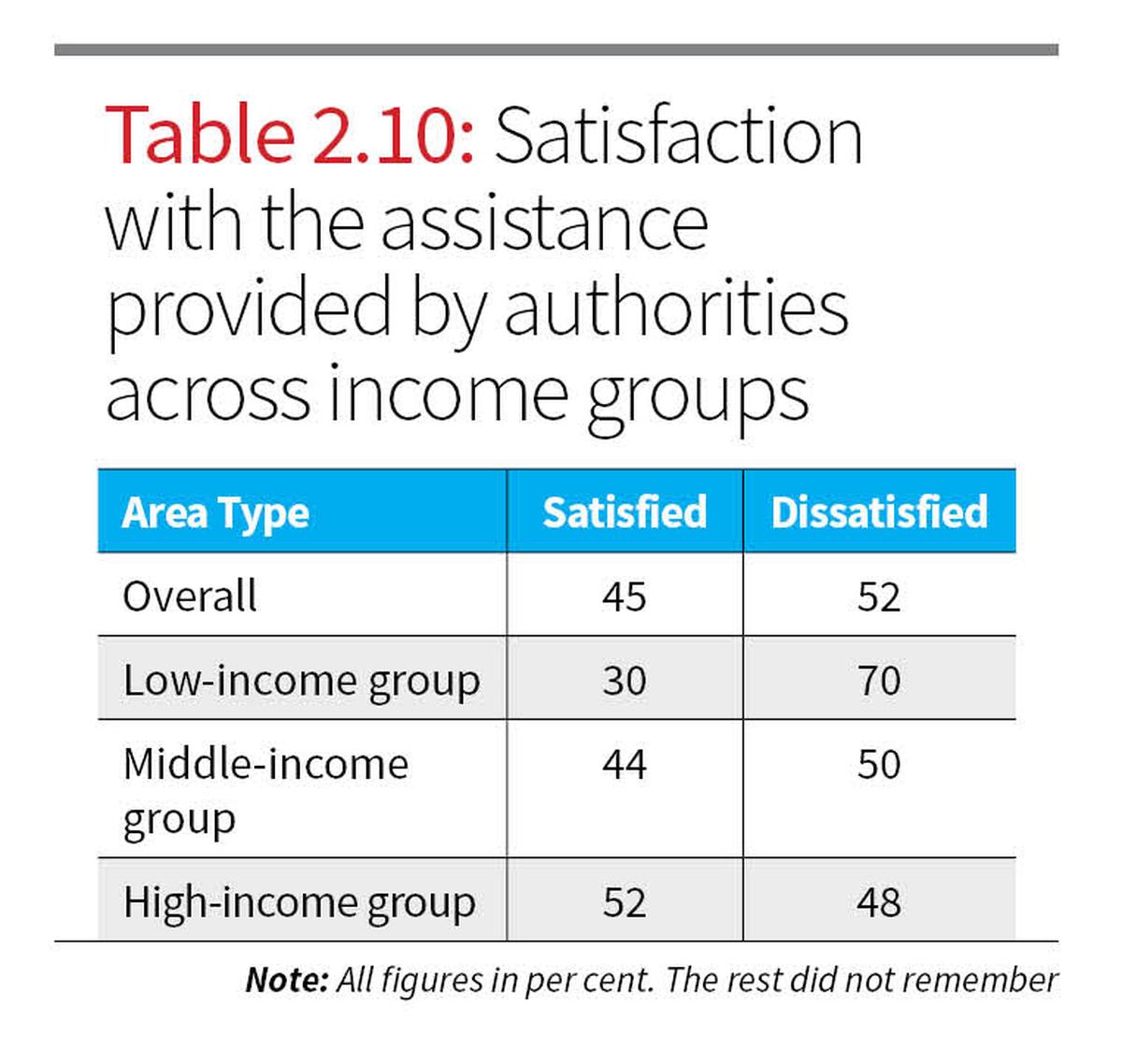

Disparities in satisfaction levels were evident across income groups (Table 2.10), highlighting systemic inequities.

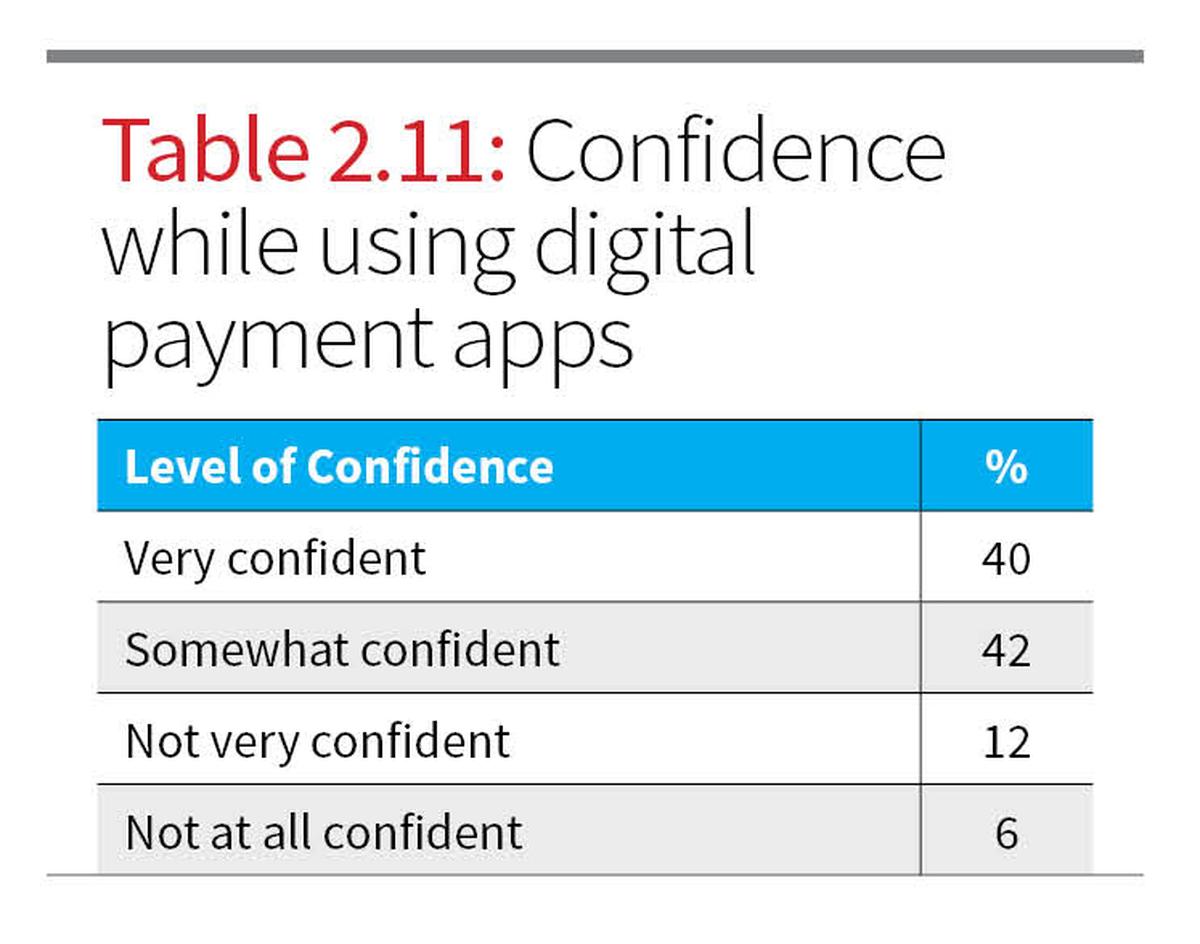

Despite these shortcomings, confidence in digital payment apps remained high (Table 2.11), reflecting continued reliance on digital tools despite limited institutional protection.

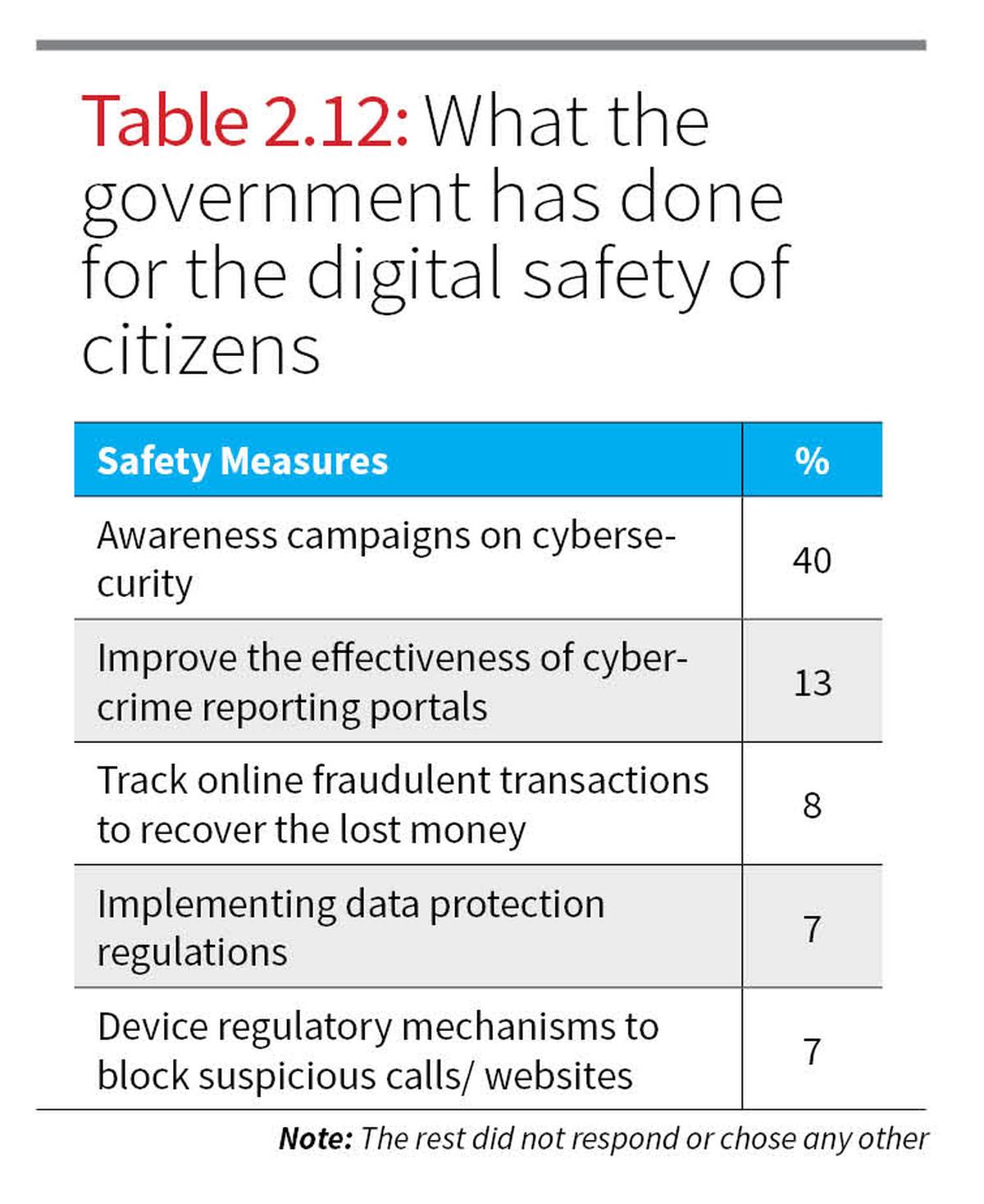

Finally, when asked about the most important government action to improve digital safety, 40% of respondents emphasised awareness campaigns, significantly outweighing support for technical fixes (Table 2.12), indicating preference for preventive education over reactive measures.

The Lokniti-CSDS survey paints a revealing portrait of Delhi’s cyber landscape, one marked by high awareness but low institutional trust, significant under-reporting, and stark socio-demographic disparities.

While most residents are familiar with cyber threats and have taken basic precautions, deeper vulnerabilities persist, especially among low-income groups who lack access to digital safeguards like antivirus software and two-factor authentication. As the city’s digital dependence grows, bridging these demographic gaps and bolstering institutional credibility must become central to any serious cyber safety strategy.

Writing Team: Krishangi Sinha, Soumya Arora, Manasvi Ghosh, Dipashi Chakma, Anshika Arvind, Samridhi Jha

Field Research Team: Dipashi Chakma, Soumya Arora, Anshika Arvind, Shefali Jain, Tushar Bhardwaj, Harshvardhan Sikarwar, Manasvi Ghosh, Zahoor Dar, Siddhant, Avantika Sarma, Samridhi Jha, Rishikesh Yadav