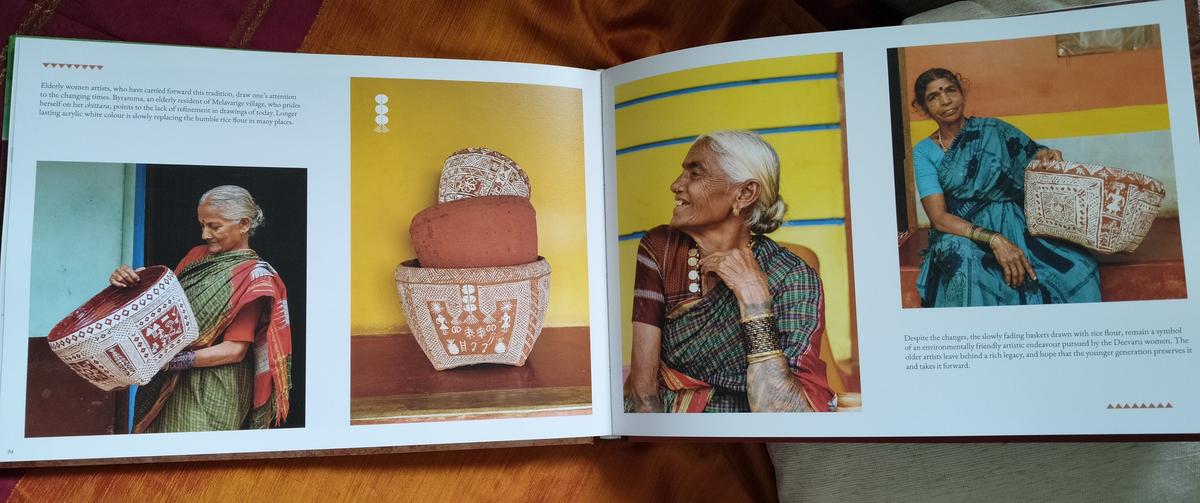

In the quiet villages of rain-soaked Malenadu region in Karnataka, walls become storytellers. Art in geometrical patterns bloom in natural hues. This is Deevaru Chittara, the traditional art form of Deevaru community, an agrarian and matrifocal group living in the region. For generations, their women have adorned walls, doors, fabric and ceremonial objects with symbols that speak of life, lineage and Nature. In their homes, Chittara survives not as a display, but as a living language. Now, through the pages of a 200-page coffee table book, it reaches a new audience. Deevara Chittara: the artform, the people, their culture (published by Prism Books), is the result of two-years of fieldwork and collaborations by three women: cultural researcher Geetha Bhat, documentary photographer Smitha Tumuluru and textile designer Namrata Cavale.

CFRIA Book team (L to R): Smitha Tumuluru, Namrata Cavale and CFRIA founder Geetha Bhat

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The trio travelled through Malenadu, covering many villages. “Every trip gave us something new,” says Geetha. “Sometimes, we felt we had missed asking a critical question and would go back.” She recalls an impromptu trip to document Kere Bete, a mass fishing festival, when the river Varada recedes. “We were informed the night before and all of us hopped onto a train at dawn.” Smitha adds, “It was thrilling and terrifying to shoot in knee-deep waters with heavy cameras.”

Chittara is more than just a visual art. It is a cultural documentation in pigments and patterns. Traditionally drawn during weddings, festivals and auspicious milestones, the motifs are geometric, delicate and symbolic. The ele or thread motif denotes familial ties. Nili kocchu, a criss-cross design represents the tatti (bamboo-strip walls) or the light filtering through the tatti. Poppali, a checkerboard pattern evokes the joints of the house rafters and the stars, believed to be ancestors watching over the living! “Even Patanga or peeti motif illustrates a butterfly perched on intersecting beams, hinting at the connection between Nature and art,” says Geetha.

It was Geetha’s first encounter with Chittara at an exhibition in Bengaluru’s Chitrakala Parishath 20 years ago that planted the seed. The conversations with the artists led her to research on the art, culture and lifestyle of this community. She later founded the Centre for Revival of Indigenous Art (CFRIA) in 2008. Her fieldwork took her deep into the villages of Sagara, Sirsi, Soraba and Shivamogga (Shimoga) taluks, where she got to see how the women returned from the fields, completed household chores and gathered to joyfully sketch the Chittara.

A fish-shaped border design ‘Bagilu chittara’ adorns the wall of a doorway at Kannada University Study Centre, Kuppali.

| Photo Credit:

Smitha Kalyani Tumuluru

Smitha, whose work explores arts, culture, livelihood and gender, joined Geetha to photograph and co-write the book. “I told her I would not be able to pay a big fee,” Geetha recalls. “Smitha instantly agreed for pay-as-we-go. I could see her passion for the work.”

Moved by the aesthetic and symbolic depth of Chittara at a CIFRIA workshop, Namrata began designing projects for CFRIA and came on board in 2018. “This book was Geetha’s dream,” Namrata says. “Though I had designed scarves and murals for CFRIA earlier, this was my first experience at designing a book and every part of it felt meaningful. As a team, we aligned on core values and aesthetics,” shares.

The most prominent expression is the Hase Gode Chittara, painted on the eastern or northern walls of homes. “It is considered auspicious,” says Geetha. Its beauty is enhanced by enclosing it within a three-sided border, the fourth is left bare, to convey visitors are always welcome to their homes. Tiny figurines of musicians often mark the bottom of this composition. The three-sided borders are also drawn at the entry door as Bagilu Chittara. The drawings are architectural in their essence, documenting the structure of the home and life. Metthina Chittara, for instance, features in two-storied houses. While Namrata’s architect-mother could verify the drawings representing the structural elements of the house in Chittara patterns for the book, Smitha’s mathematician-father decoded the underlying geometry and symmetry in the motifs, highlighting the community’s intuitive brilliance.

The floral motifs — Chendu hoovu — appear as a single flower or torans (festive garland), while malli hoovu shows up as a saalu (linear pattern). A nesting bird, Goodina hakki, represents a female bird waiting for her mate. “The madanakai (L-shaped wall brackets) on either side of the hase gode chittara not only represent the beams, but metamorphically indicate extension of families,” explains Smitha.

People rush into the shallow waters of Hecche panchayat lake during the annual community fishing event — ‘kere bete’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Chittara also documents ceremonial objects such as basinga and tondla, headgears for the bride and groom, painted as ornamental motifs, while the Vastra Chittara, drawn on a cloth is used to wrap and store these objects post-wedding. The Tiruge mane, a carved pedestal used for placing offerings, has its own chittara representation. The moole aarathi is drawn on the eechalu chaape (grass mat) during weddings. This pattern is drawn as small as an 8-moole (8 corner) aarathi chittara to as big as 64 or 160 cornered-patterns. “How these corners are connected is left to each artist’s creative interpretation,” says Namrata.

The four colours used in Chittara are rooted in ecology. Red is drawn from kemmannu (red earth) or raja kallu (red stone); white from soaked and ground rice or jedi mannu (white clay); black from roasted rice grains and yellow from the seasonal fruit of Guruge tree, a species of Garcinia. “Since yellow pigment comes from a specific seasonal fruit, it is used sparingly,” reveals Smitha, while the brush – pundi naaru, is made from a variety of jute fibre.

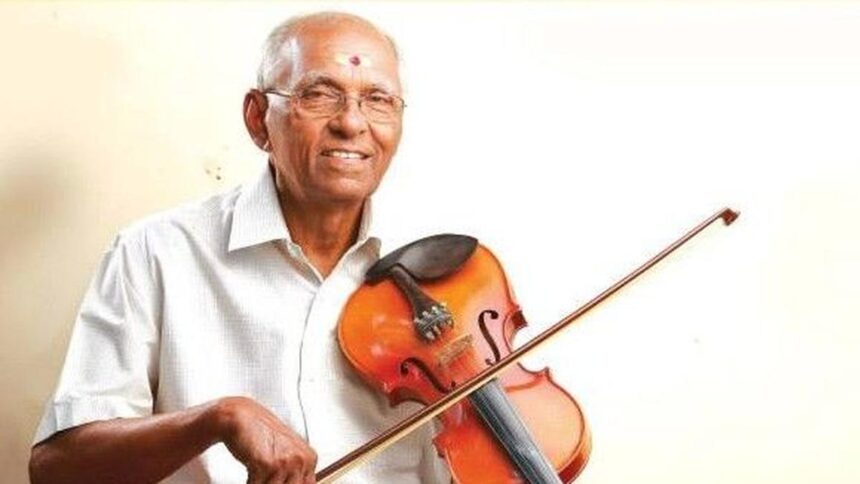

The book captures the life and culture of the community

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The book is a careful-curation of all these layers. Each section walks the reader through the history, motifs, rituals and evolving social landscapes of Deevaru community. “We have used colloquial Kannada for Chittara motifs such as ele, patanga, moole, poppali, but catalogued all in the glossary section,” says Geetha. Namrata’s design philosophy was to create breathing space for the art. “This was not just about layout, but about reverence,” she says.

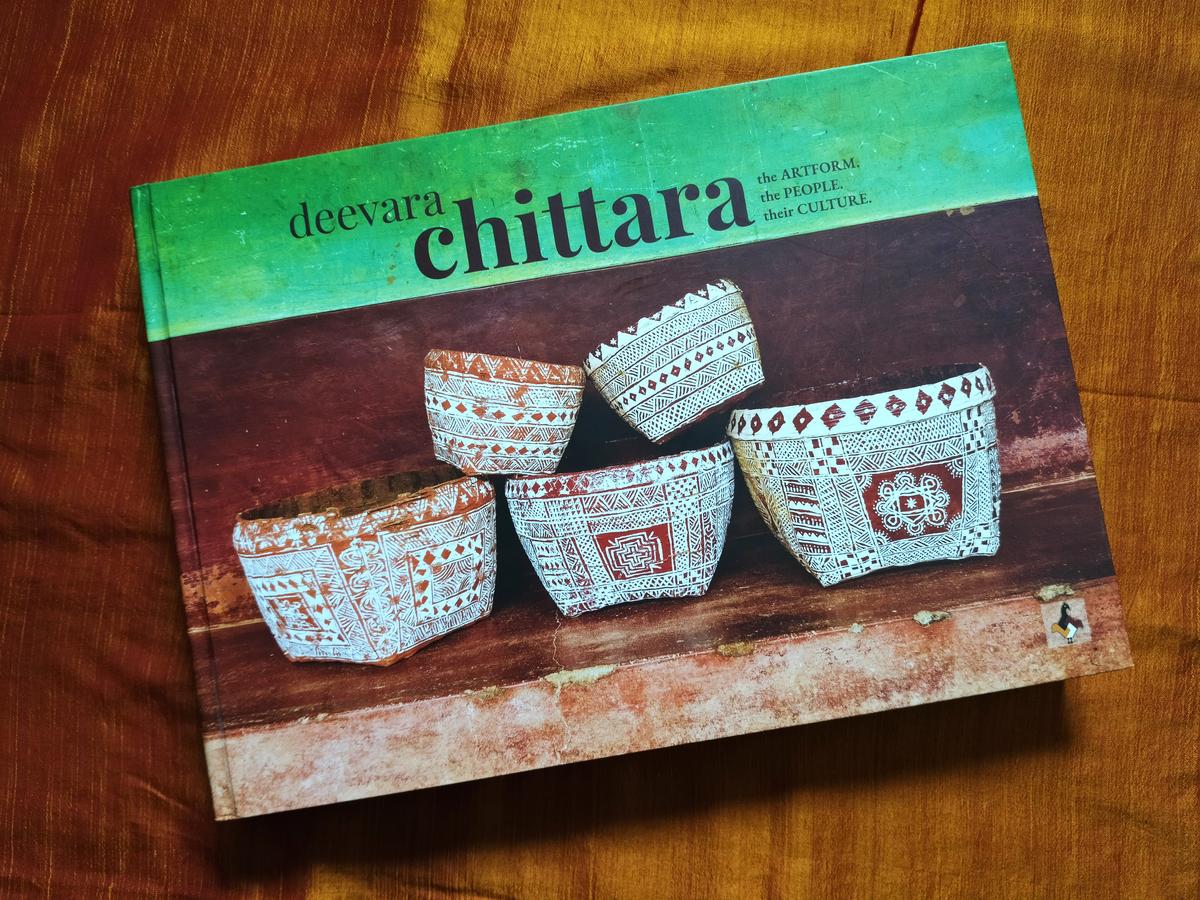

The book cover

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The festive fairs in the villages are adapted into therina chittara. The painting of theru (chariot) depicts the devaru (deity), placed in the centre and people pulling the chariot. Among the most interesting rituals of the community is Bhoomi Hunnime Habba, a festival that celebrates mother earth. Held on the full moon before Deepavali, this resembles a seemantha or baby shower for the earth. Deevaru women prepare charaga (rice porridge with greens and vegetables), carry many delicacies in a Chittara-painted basket called Bhoomanni Butti and offer portions not just to each other, but also to birds, rodents, snakes — everything that share the field’s ecosystem. “For them, nature is god,” says Geetha.

CFRIA’s mission goes beyond the book. It conducts exhibitions, workshops and invites women from the community to paint walls of varied institutions. I wish to take this beautiful artform and living tradition and culture of the Deevaru community to the outside world,” says Geetha.

Published – August 04, 2025 05:51 pm IST