Fifty years after it first swept the nation, Sholay remains a sensory experience like no other. Like the inebriated Veeru (Dharmendra) shouting from atop a water tank in the weary lanes of Ramgarh, its story brims with drama, emotion, and action — this Trioka has made mainstream Indian cinema a global force. The 4K restoration amplifies every detail: adding thump to Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan) and Thakur Baldev Singh’s (Sanjeev Kumar) footsteps, a fresh zing to R.D. Burman’s iconic music, and a brighter glow to Basanti’s (Hema Malini) rustic charm. Yet beyond the spectacle, it is the portrayal of a village grappling with anxieties, anger, and change that remains as potent today as it was half a century ago.

The poster of the film

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Released on August 15, 1975, in the midst of the Emergency, this subversive tale arrived on screens at a time when the moral ambiguity of its heroes perhaps struck a chord with audiences weary of the one-dimensional righteousness of its stars.

At its heart is Thakur, a retired police officer shaped by a bygone era, failed by the very system he once served. After suffering a personal loss at the hands of Gabbar, he chooses not to approach his former colleagues in khaki. Instead, reposes his faith in two winsome crooks — Jai (Amitabh Bachchan) and Veeru — to get him justice.

These petty outlaws, themselves outsiders, become the arms of a morally upright man whose limbs were dismembered by a cold-blooded bandit. It is a gripping reimagining of the body politic that may have proved cathartic for an audience struggling to find ways to combat corruption and high-handedness in daily life.

Five decades later, the purpose of the Thakur seem relevant, the camaraderie between Jai and Veeru hasn’t lost its charm, tears for Radha’s (Jaya Bachchan) fate haven’t dried and Gabbar continues to evoke the fear of the unknown.

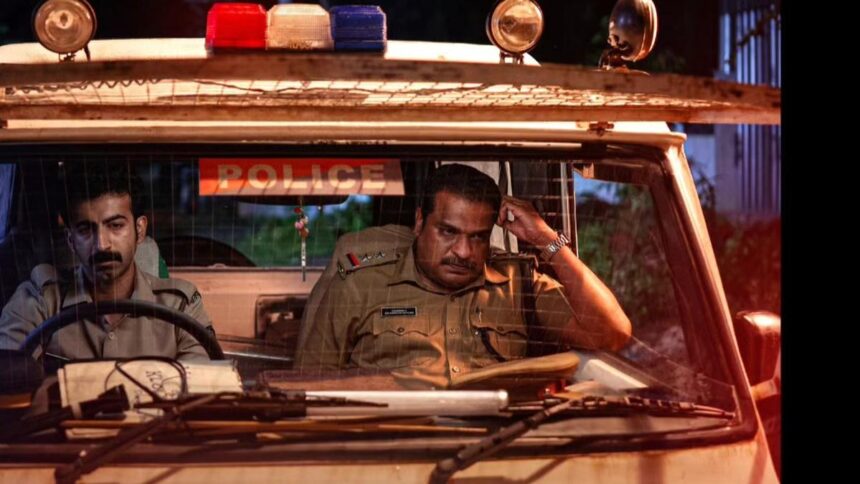

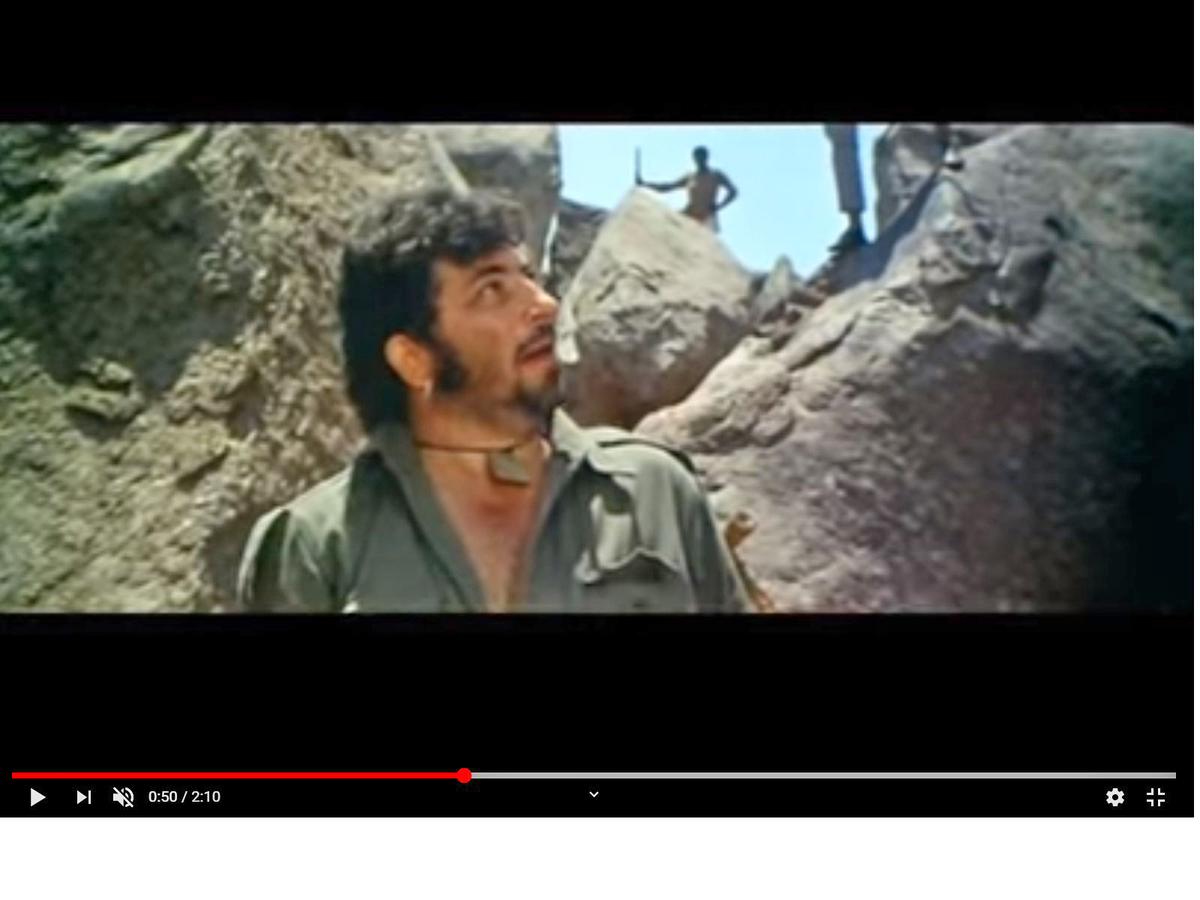

The famed scene where the Thakur loses his hands

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Of course, writers Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar (famous as Salim-Javed) drew inspiration from Seven Samurai and the American Westerns. They also drew characters from Gunga Jumna and Mera Gaon Mera Desh, But in creative cultivation, it’s not the seeds that matter — it’s the harvest that endures.

Sholay was not the first film to explore themes of dacoits, revenge and friendship; nor a first where horses galloped parallelly to railway wagons. But the way all of it came together in Sholay, has kept generations hooked. From Raj Kumar Santoshi, Anurag Kashyap, Vishal Bhardwaj to S.S. Rajamouli, the recipe has inspired the cinematic gaze of filmmakers.

The year 1975 was a watershed year for Hindi cinema. After placing the character of a ‘mother’ at the centre of the narrative with Deewar, Salim-Javed rewrote the rules in Sholay by removing the mother-figure from the picture and striking a balance between melody and malevolence, songs and dialogue. Sholay’s LPs played even dialogues such as — ‘Kitney aadmi they’ and ‘Saab, maine aapka namak khaya hai’ — in the living rooms and neighbourhood pan shops. The film also turned its side characters — Soorma Bhopali and Sambha — into household names. Interestingly, unlike many films of its era, Sholay’s songs may feel somewhat dated today, yet its writing continues to invite fresh interpretations.

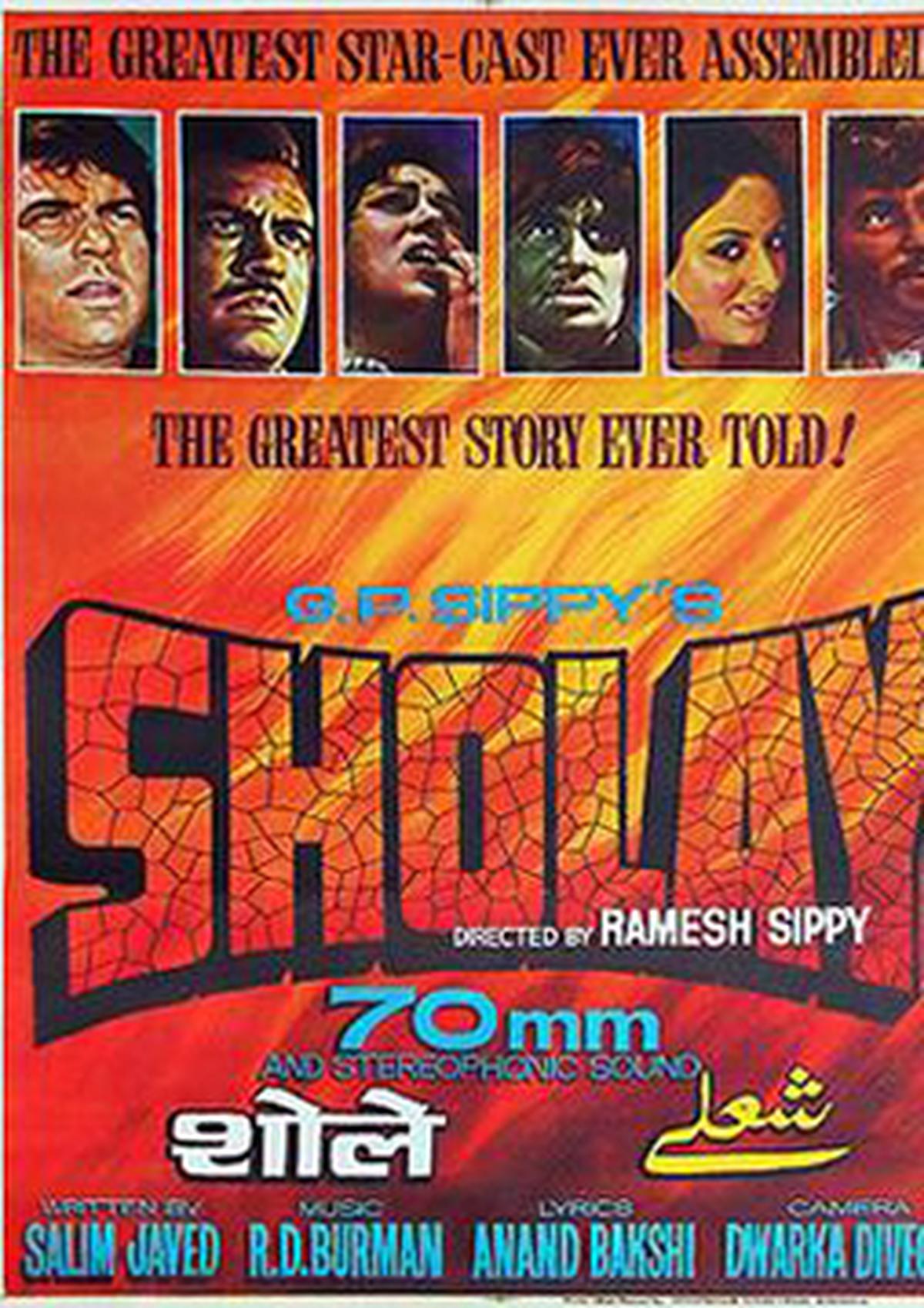

Amjad Khan is inimitable as Gabbar Singh

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Salim-Javed aimed to tell a great story with compelling characters. Yet, woven between the lines of this fast‑paced entertainer are subtle reflections on lawlessness and community resilience — themes as relevant to contemporary debates on justice and morality as they were in the 1970s. Its characters speak to you, and the revenge at the heart of the story invites re-examination in its social and political context. Here, every character has a back-story, except for the villain. Was Gabbar a product of backward-class resistance, asking for the upper-caste Thakur’s ‘hands’ as an assertion of his place in the socio-political hierarchy? Was this the reason that the ruthless Gabbar became a much-loved villain? When Thakur invokes the ‘iron-cuts-iron’ principle by setting Jai and Veeru against Gabbar, does it imply the caste equations and social justice politics that would shape the future?

When Imam Saahib asks: “itna sannata kyun hai bhai (why there is so much silence)” after his son is killed by Gabbar’s men, it breaks the stereotype that, for a devout Muslim, religion comes first. Here, the old man sacrifices his son for the welfare of his village. We also mourn for Jai’s unfinished story with the widowed Radha. Was it because the society was not prepared for widow remarriage? However, the film then portrays Basanti as a working woman in a rural setting. Social and political correctness evolve, but heartfelt emotions remain unchanged.

The story and screenplay is written by Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar

| Photo Credit:

AFP

Right after the massacre of Thakur’s family, Helen’s Mehbooba Mehbooba number softens the blow. Soon you realise nobody can hold a gun like Amitabh Bachchan — it feels like an extension of himself. When he flips the coin to decide who will stay back to fight the dacoits, it’s evident that he is the film’s head, while Dharmendra is its heart. Amidst all the dialogue-baazi, Jai’s quiet arrival riding a buffalo and Radha’s subtle half-smile create a silence that lingers long after.

Speaking about Salim-Javed’s contribution, Ramesh Sippy once told me the narrative was so strong on paper that the film would have worked, irrespective of who directed it. But would it have become a classic, with every scene etched in memory? That level of greatness was achieved because everyone involved brought their best to the film.

Ramesh Sippy, the director of Sholay

| Photo Credit:

PTI

It was one of the first films to be shot entirely outdoors and Ramesh worked with a cameraman who had never worked outdoors before. Dwaraka Diwecha was a master of indoor shooting. Such was his mastery over cinematography that when the director would say the word, ‘cut’, and look at him for confirmation, he would move the camera without looking into it. However, for Sholay, Dwaraka researched thoroughly to bring Ramesh’s vision alive.

Can a Sholay be made again? Maybe not. In polarised times, the temple-scene where Dharmendra gives voice to the idol of Shiva, would cause an uproar. People might ask the surnames of Jai and Veeru and identity politics would come into play in the battle between the Thakur and Gabbar. The ‘greatest story ever told’ would have been reduced to a woke essay. Moreover, no corporate entity today would back a film whose budget more than doubled during the shoot.

Published – August 15, 2025 03:36 pm IST