This evening (August 29), the third segment of the Edict Project ‘Ashoka and Ecology’ will be held at the Ashoka University’s campus. Nayanjot Lahiri, professor of History at the University, has been deeply involved with the project as a consequence of the University’s partnership with Carnatic vocalist T.M. Krishna.

Krishna, and artistes such as M.K. Raina, Kapila Venu and Justin McCarthy (Ashoka University), have teamed up to musically and artistically re-imagine the emperor’s edicts. Nayanjot, along with Naresh Keerthi of Ashoka University, has had conversations with the artistes and has helped them understand and interpret the words of the edicts.

Nayanjot Lahiri, M.K. Raina, Naresh Keerthi and T.M. Krishna at the 2022 edict release event

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Ashoka University

Nayanjot is the award-winning author of two deeply researched books on the Mauryan emperor who ruled Magadha from 268 BCE till his death in 232 BCE: Ashoka in Ancient India and Searching for Ashoka: Questing for a Buddhist king from India to Thailand. Her books are the result of numerous extensive trips to the various sites where Ashoka’s imprint is seen.

In rugged landscapes across the country, immutable, stand these edicts, literally writ in stone. The persona of the emperor in Nayanjot’s books and in this project is close to what Ashoka himself put out — from being compassionate towards living beings to unique ideas of governance as well as personal fears and limitations.

The Khandahar Edict of Ashoka.

| Photo Credit:

Wikipedia

These are the messages of a king who forswore war and thought of humanity at large after waging the most sanguinary war. Ashoka lives on, and his words speak with the same immediacy and effectiveness today as they did nearly 2,300 years ago when they were first chiselled on boulders, rock crops, pillars, in caves and near what were once urban sites. These are found in 50 sites all over India and beyond — in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Odisha, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka as well as in Afghanistan, Nepal, and Pakistan. The majority of the edicts are in the Prakrit language, while some are in Greek and Arabic as also Kharosthi; the common script is Brahmi.

“Ashoka has fascinated generations of Indians. There are many reasons for this. He not only ruled the largest empire of ancient India but also wrote himself permanently into Asian religious history by moving towards Buddhism. He had fought a great war and won it, but he believed that the human toll of his conquests was a moral defeat.” This is how he presents himself in his Kalinga edict and it is a striking message,” says Nayanjot.

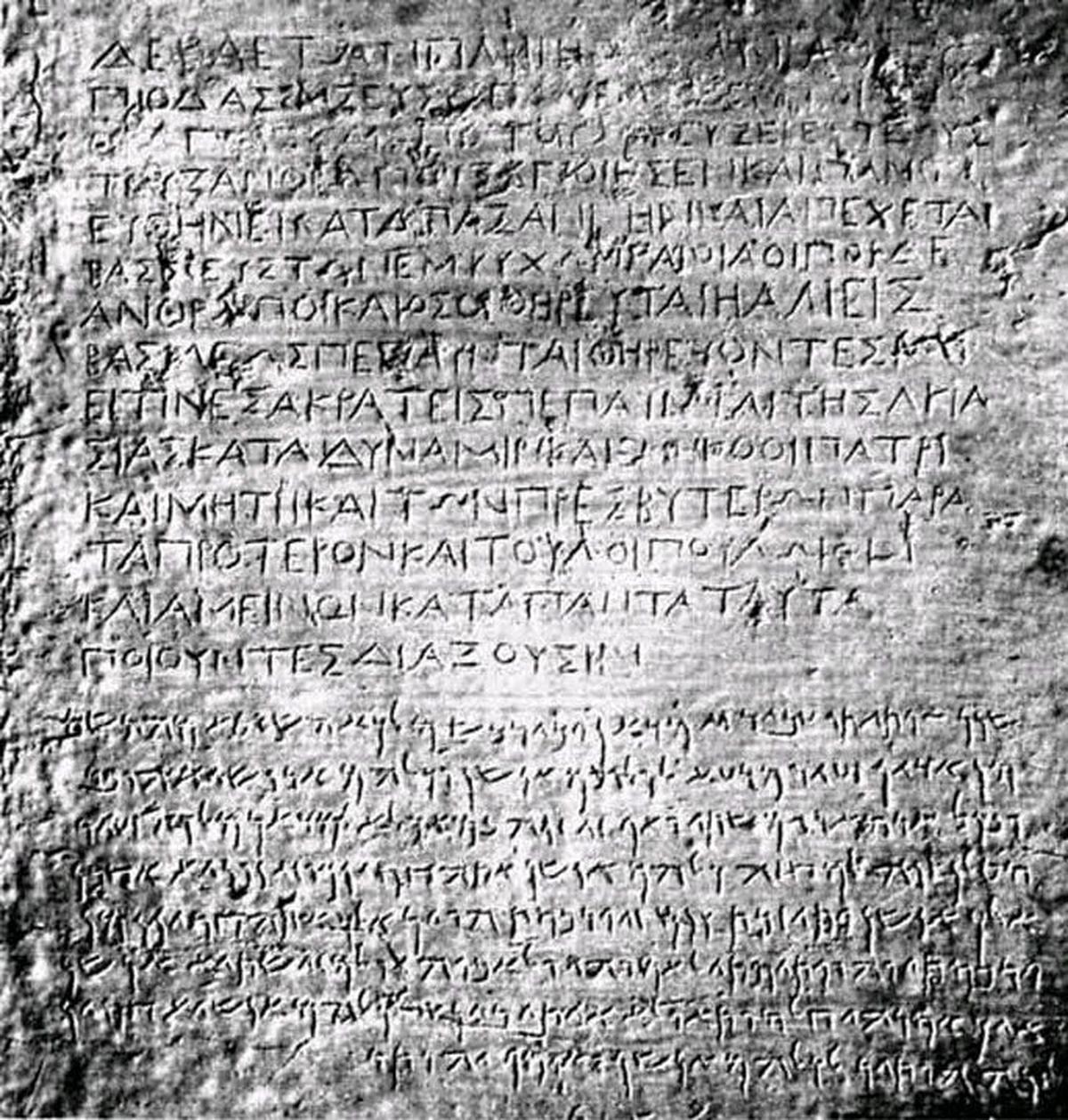

Ashoka’s Sannati edicts

| Photo Credit:

Nayanjot Lahiri

His relevance to contemporary times is also because he was a master communicator. “Today we have television and the social media. But millennia ago he communicated his messages to be heard — for millennia.”

In the early edicts, he talks about Buddhism, but in the later ones, his focus is on speaking about novel modes of governance that he introduced, and what he believed should be the norms of public and personal conduct,” she points out.

However, Nayanjot contests the interpretation of Ashoka as an exemplar of non-violence. “If you look at the Kalinga edict in its total context, you realise that there is violence there. And not just in relation to Kalinga which he regrets and repents. Ashoka’s message of his moral defeat and his metamorphosis into a man of peace gets muddied because he is threatening forest dwellers in the same Kalinga edict. This really comes back to the fact that the state cannot control all its land, it cannot control all its people. In such instances, non-violence is inevitably situated within the practice of violence.”

What makes him most interesting to Nayanjot is that Ashoka was an all-India figure, she says. “This has to do with the ways in which the emperor made himself visible through his edicts in large parts of the Indian subcontinent. Uniquely among world rulers of his time, Ashoka appears to us not through the chronicle of a courtier, or a visitor to his kingdom, or by religious hagiography but by speaking carefully and deliberately in his own voice. There were many kings and emperors before him but they didn’t speak to their subjects and thus, to us.”

Among the edicts, Nayanjot’s favourites are the Queen’s edict in Allahabad and the edicts in the Deccan. In the former, Ashoka’s queen Karuvaki says all the donations that have been made by her have to be registered as the mother of Tivala (her son). The queen instructs it has to be put down. “It shows Ashoka gave space and agency to women”.

Ashoka’s presence (epigraphic imprint) in the Deccan is far larger than in any other region. “This highlights that Ashoka is as much an emperor of the Deccan as he is of north.”

The Edict Project seeded by Krishna is about “reimagining Ashoka’s words in musical and artistic forms as also create vibrant academic, socio-political and aesthetic conversations around them,” elaborates Nayanjot. “Krishna’s interest and curiosity are remarkable; I feel I have been enriched working with him.”

Published – August 25, 2025 05:08 pm IST