India’s fascination for headgear does not only extend to the socio-religious ambit with taqiyah, EXPLAIN taqiyah turbans or traditional Bengali topor, but also to the politico-cultural zeitgeist. Remember the famous Gandhi topi that made a comeback with social activist Anna Hazare’s 2011 hunger strike for The Lokpal Bill? The accessory came to define the sartorial choices of many freedom fighters too, take Bhagat Singh and Subhas Chandra Bose, for instance. In the world of sports, also, baseball caps and cricket hats have been nothing short of a style statement.

MUMBAI, 07/04/2011: Social activist Anna Hazare on the third day of his fast unto death campaign, demanding anti-corruption law on the lines of Lokpal Bill, at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi. Supporters of Anna Hazare wearing Gandhi Topi and holding a tricolour in her hand participate in rally, ‘India Against Corruption’ at Azad maidan in Mumbai on April 07, 2011.

Photo: Vivek Bendre

| Photo Credit:

VIVEK BENDRE

An unmistakable pick for a sunny day on the beach, a polo match or a derby, hats have always been around. They may assume a prominent spot on the accessories vertical of leading fashion retail brands that also dabble in apparel, but only a handful of people in India tread the road less travelled that leads to the artsy-craftsy world of millinery.

Passion project

Shilpa Chavan who runs the label Little Shilpa, founded in 2008, is the first that comes to mind.

Shilpa Chavan, the first Indian milliner to have designed headgears for celebrities like Lady Gaga and Sonam Kapoor

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The Mumbai-based milliner might as well be called an artist for the post-modern aesthetics she employs to her dramatic headpieces that are a cross between fascinators and wearable art. She is the first Indian milliner to design headgear for celebrities like Lady Gaga and Sonam Kapoor, while also stamping her presence on runways — be it designing headgear for contestants and hosts of beauty pageants in the 1990s or showcasing her headpieces at Lakme Fashion Week in 2009, followed by London Fashion Week, Paris Fashion Week and Milan Fashion Week.

“Of course, headgear is embedded in India’s cultural narrative. Hat making or millinery is a craft, just like embroidery. I did a military-inspired collection in 2011 and was scrounging for someone who makes Gandhi topis, but could only spot one man in Mumbai. So, I got him to replicate the topi in the fabric I wanted. Sadly, millinery is not recognised,” she says. Stating that headgear can be too “costumey”, Shilpa says it has to be functional too, especially when it goes into a retail space.

Little Shilpa’s military-inspired collection

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Functionality is in fact one of the reasons why Ahmedabad-based Nirali Rangwala, who founded Maaneh Millinery in 2018, introduced sun hats to her eclectic collection of fascinators, derby hats and berets last year. “Historically, though Indian men have always been sporting hats and headgear, Indian women covered their heads with the pallu of a sari, a dupatta or a scarf. To Indian women, the concept of hats was introduced by colonisers. So, I wanted to create hats that could be worn in the sun, let alone occasions like polo matches or a derby,” she says.

Ahmedabad-based Nirali Rangwala, who founded Maaneh Millinery in 2018

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Nirali, who is an aerospace engineer by profession, was enticed by millinery in Kentucky in 2011. “I was working in Kentucky. It is known for the derby. I was mesmerised by fascinators and hats sported by women at one of the derby events there. I learnt the craft from Jenny Pfanenstiel, who is based in Louisville, and then attended several workshops on millinery,” she adds. Nirali started the brand soon after getting married. “I was beguiling my time with millinery in Gujarat, after I got married and shifted to India, when my husband and in-laws took note of my creations. They were impressed and suggested that I started a brand. That’s how Maaneh Millinery was born,” she recollects. Stating that Maaneh translates to respect, honour, esteem and regard in Sanskrit, she associates the term with the feeling a hat could evoke. “It’s like a crown,” she says.

Crafting techniques

Shilpa could not agree more. “I have always been fascinated with crowns that our gods wear. That was the sub-conscious idea that sparked my curiosity about headgear. There’s this unsaid power in a head dress. I studied fashion, but I always struggled with seasons, rules, tailors. I am a more hands-on handicrafts person. Millinery is my canvas, where I can tell whatever story I want,” she says.

Shilpa tells her stories though hats using unconventional materials, from bangles to paper cones and rubber-slipper thongs to Plexiglas

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Shilpa does tell her stories through hats using unconventional material, from bangles to paper cones and rubber-slipper thongs to Plexiglas. “I sometimes use seven to eight different techniques and it requires knowhow of structural and architectural elements associated with millinery. These techniques include laser cutting, laser soldering, sometimes pieces are constructed with hot glue or held together with just wires. Millinery is like embroidery in the air,” she shares. Shilpa comes armed with a solid training in millinery, which she studied at Central Saint Martins, London, under the Charles Wallace India Trust Scholarship by the British Council and later interned with ace milliner Philip Treacy. Her biggest takeaway: “Always turn the hat upside down and see what it looks like from the inside. Also, how well does the hat balance.” She adds that the only reason she accepts an order on millinery is if she is convinced that it is creatively enhancing, challenging.

Namrata Lodha, founder and head designer of Myaraa, a five-year-old luxury hat brand of India

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Most milliners are particular about the headgear’s base fabric. Namrata Lodha, founder and head designer of Myaraa, a five-year-old luxury hat brand of India, gravitates towards natural, breathable options. “We like raffia and wheat straw because they’re light, summery, and luxurious. When we’re looking for something with more structure and a timeless feel, we turn to vegan felt. If I had to choose a favourite, it would be straw,” says Namrata, who was initiated into hat making by a propitious vacation in America. “I was visiting my son, who was planning a trip to the Bahamas with his wife. They had picked up a few hats for the vacation, and I asked them if I could embroider their names onto the hats. Later, their friends started asking if I could make some for them too. That’s how Myaraa came into being.”

Tuft Hat by Myaraa

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The brand makes all its hats in India, in Harda, Madhya Pradesh. “Our production is seasonal. We wait for the wheat harvest to finish so we can use fresh straw. It’s a very organic process, rooted in the rhythms of the land. When I started Myaraa, I wanted to build more than just a brand; I wanted to create opportunities. So, I trained women from my town, many of whom had never done craft work before, and today they are the skilled artisans behind every piece. It’s a small, close-knit setup, but there’s so much heart that goes into every hat we create,” she adds.

The hatter’s toolkit

Tools used by Nirali for making intricate flowers using French and Japanese techniques

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Millinery is both, time-consuming and dexterous. Shilpa and Nirali confess to having spent days, sometimes even weeks to make just one piece. “I use a lot of Indian textiles and the collections are based on Pantone pigments. Sinamay abaca fibre fabric is the base material made out of banana plant, which is my preferred choice for the base fabric. I use French floral techniques on silk, organza, velvet and leather. Also, Japanese origami fabric and paper-flower-making techniques are used for various trims, alongside intricate feather work. My recent collection of fascinators is quite floral,” explains Nirali. She also points at many fascinators that feature embellished mesh veil, with rhinestones, pearls and Swarovski. Her hats start at ₹4,000 and can go upto ₹50,000. Maaneh Millinery operates out of a workshop-cum-studio in Ahmedabad, with Nirali joined by two assistants.

Actress Huma Qureshi in a fascinator designed by Nirali’s Maaneh Millinery

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The pricing of hats often depends on its artistic value that is determined by the quality of material used, structural detailing, labour and many other factors. For Shilpa, it is the technical knowhow. “I don’t use a mould for making hats, like most milliners, as I find it too restrictive. But I love experimenting with new materials, from plastic toys to mirrors and Swarovski. I work from home and with just two or three assistants,” she says. Her creations are priced above ₹10,000.

Shilpa is known to have created headgear for collection campaigns of ace fashion designers, like Sabyasachi, Boudicca, Tarun Tahiliani, Varun Bahl, Manish Arora, Manish Malhotra, and Wendell Rodricks. Myaraa is not far behind. Last year, Namrata’s brand teamed up with fashion designer Payal Singal for The Blossom Collection of hats. “Each hat in this collection is a celebration of summer with floral embellishments, eco-friendly materials,” informs Namrata. A few years ago, Myaraa had teamed up with Kate Stoltz, a New York-based designer. The brand’s hats are priced between ₹1,999 and ₹11,799.

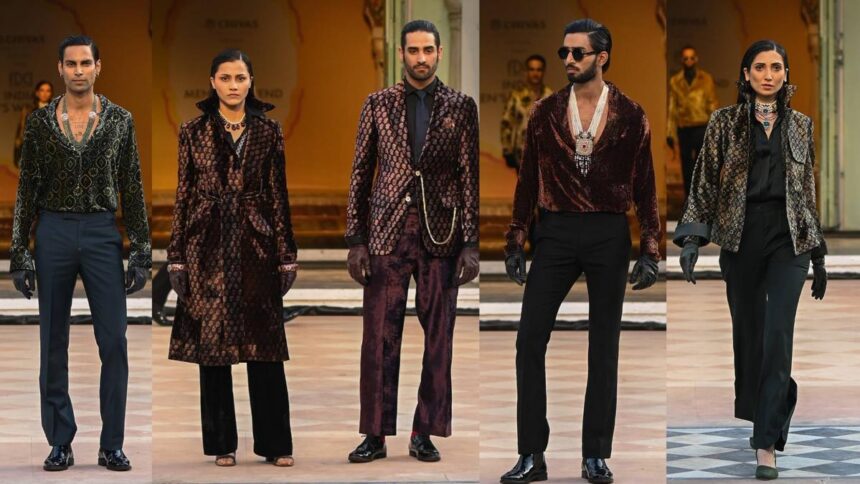

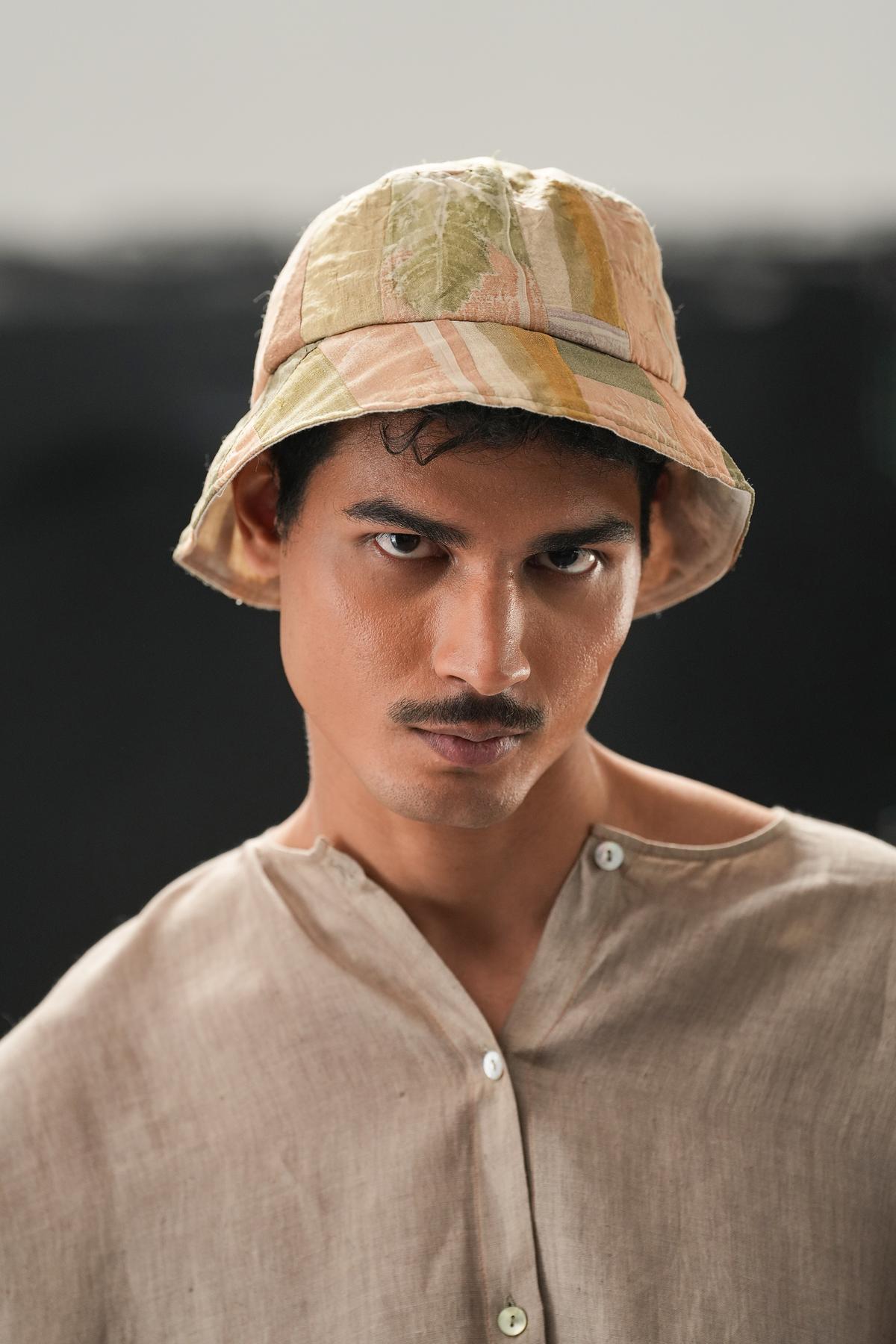

Fashion designer-cum-milliner

It should be interesting to note that while top milliners, like Stephen Jones and Philip Treacy, made hats for fashion designers and significant pop culture icons, many prominent fashion designers too became famous for their hat designs. The list includes Coco Chanel, Christian Dior and Lilly Daché. In India too, some fashion designers have taken to millinery — from Delna Poonawalla, Nitin Bal Chauhan and Nida Mahmood to Kunal Rawal and Ritu Beri. We spoke to Delhi-based couturier Urvashi Kaur, whose recent collection ShinSei showcases bucket hats made from scrap fabric. “The hats are not knitted; they’re constructed using textile waste through patchwork technique. Each piece is reversible, and some include thread embroidery. We developed unique patchwork layouts that allowed us to use even the smallest kathran (fabric remnants) from the studio floor,” says Urvashi. The hats range from ₹3,500 to ₹6,800.

Fashion designer Urvashi Kaur’s recent collection ShinSei showcases bucket hats made from scrap fabric

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

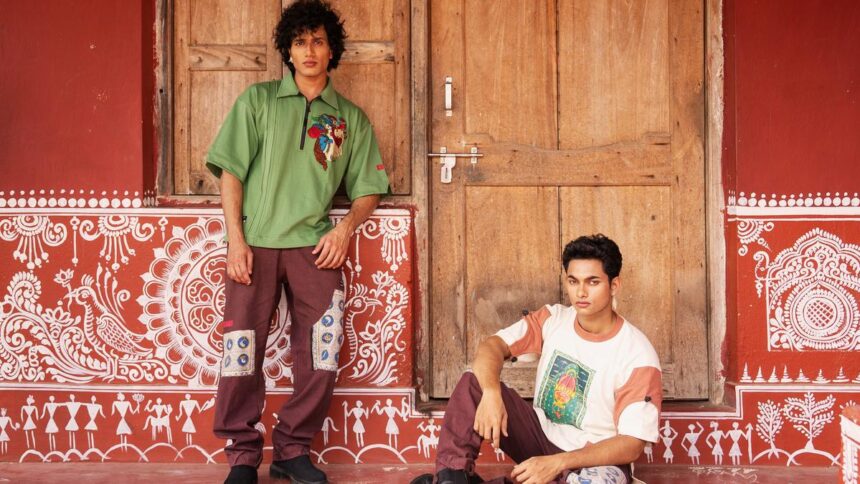

Many Indian apparel-and-accessory brands have also started adding hats to their business verticals. You may find hats by Next, Chokore, which sells all kinds of accessories from bags to shoes, Odette, which recently ventured into millinery, or One Less, which, like Myaraa, is also romancing raffia. Its founder Hansika Chhabria, who started One Less in 2021, has introduced a range of raffia hats.

Raffia hat by One Less

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

“Made from segments of raffia palm trees, raffia is sourced from Madagascar. The fibre became popular in 2022 and it is here to stay. We included hats in our brand in 2023 and have only crafted them from either organic cotton or raffia because One Less promotes sustainable fashion and is committed to minimising environmental impact,” says Hansika.

While sustainability appeals to Hansika, Mamta Roy, founder of Odette, pivots on variety. The brand offers sun hats, bucket hats, wide-brimmed hats, berets, cloche hats, classic pillbox hats and fascinators starting at ₹960. “Our hat-making process combines both traditional and contemporary techniques to create unique and exquisite pieces. We use hand-blocking to shape the hats, followed by stitching and embroidery to add intricate details. There’s appliqué work and beading too,” says Mamta, of her five-year-old brand.

Odette offers sun hats, bucket hats, wide-brimmed hats, berets, cloche hats, classic pillbox hats and fascinators

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Shilpa has not launched a new collection since 2018, and is now mixing millinery with filmmaking. Namrata and Nirali have no such plans. “We’ve seen about a 30% to 35% increase in sales year-on-year, especially as people travel more and experiment with personal style,” says Namrata. Maaneh Millinery too has recorded a 20% rise in sales. “The biggest challenge for a milliner in India is changing perceptions. Hats haven’t been part of everyday modern fashion here, most people see them as something just for vacations or weddings. Educating the market and making hats feel relevant to Indian lifestyles has taken time,” says Namrata about the challenges that milliners like her have weathered to paint the landscape of India’s fashion industry with vibrant hues.