When India debates pollution, the spotlight usually falls on coal plants, cars, or power generation. Rarely do we look inside our wardrobes. Despite its polished and glamorous exterior, the fashion industry is, in reality, one of the dirtiest sectors in practice. On a global scale, the industry utilises approximately 79 billion cubic meters of water, contributes 8-10 % of greenhouse gas emissions, and generates 92 million tonnes of waste annually. India stands as the world’s third-largest textile exporter and a rapidly growing consumer market, positioning itself as both a contributor to the issue and a key player in any potential resolution.

A portion of the bathing ghat at the Cauvery abutting Arulmigu Magudeeswarar Temple is clogged with clothes and other articles discarded by devotees, in Erode.

PHOTO: M. GOVARTHAN

| Photo Credit:

GOVARTHAN M

Mountains of waste and rivers that turned toxic

Clothing continues to contribute to pollution even after it has been purchased. Washing synthetic fabrics such as polyester or nylon releases microscopic fibres that can evade wastewater treatment facilities. These fibres find their way into our rivers, ultimately contaminating seafood sourced from the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Recent studies reveal the presence of micro plastics in salt, drinking water, and even within human blood and lungs. Experts caution about the potential for hormonal disruption, increased cardiovascular risks, and associations with cancer. Textile pollution poses a dual threat, impacting not only the environment but also infiltrating our bodies.

A worker drying clothes after the dyeing at a unit in Tirupur in Tamil Nadu. Photo: K. K. Mustafah

| Photo Credit:

MUSTAFAH KK

India produces ~ 7,800 kilo tonnes of textile waste annually. In contrast to plastic or electronic waste, there currently exists no Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) legislation compelling brands to collect or recycle their products. Once discarded, garments accumulate in landfills like Bhalswa in Delhi and Deonar in Mumbai, where they smoulder and release harmful toxins into the environment. Synthetic fabrics, which have become commonplace, require centuries to decompose. Every polyester T-shirt discarded today could potentially endure longer than the individual who once wore it.

Textile chemical effluents flowing in odai at Ammapalayam merge with River Noyyal in Erode.

Photo: M. Govarthan

| Photo Credit:

GOVARTHAN M

Textile clusters across the country are showing visible impacts. Tirupur in Tamil Nadu, previously recognised as the knitwear capital, discharged a significant amount of untreated dye into the Noyyal River, prompting the Madras High Court to order the closure of hundreds of units. Ludhiana’s dyeing mills, Surat’s polyester factories, and Kanpur’s tanneries persist in discharging chemicals into rivers and groundwater. The Central Pollution Control Board has identified textiles as one of the top ten industrial polluters.

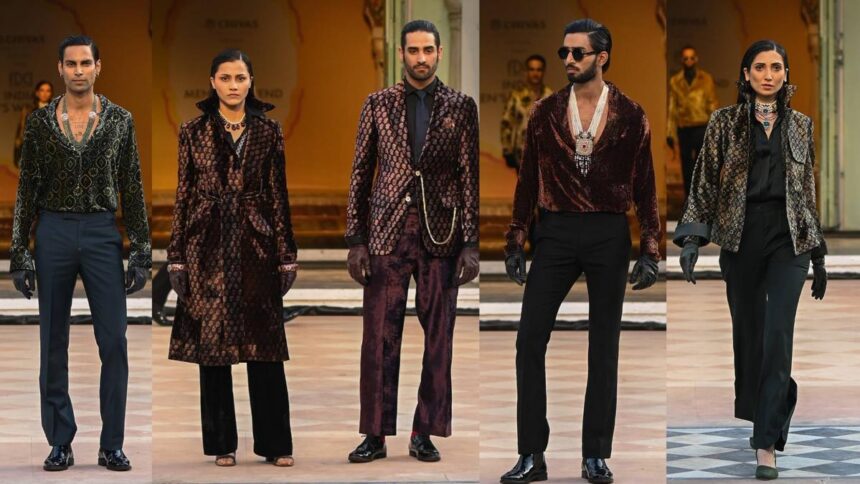

Workers stitching garments at a knitwear export unit in Tirupur.

Photo:S. Siva Saravanan/ The Hindu

| Photo Credit:

SIVA SARAVANAN S

Why can India not afford a delay?

The stakes have never been higher. India is home to 20 of the 30 most polluted cities globally, with nearly 40% of its rivers deemed too contaminated for bathing. India has been positioned at 105th among 125 countries in the Global Hunger Index, highlighting significant challenges related to food and water security. The accumulation of textile waste exacerbates these crises. A circular fashion economy has the potential to transform the landscape by decreasing fibre imports, generating employment opportunities in repair and recycling, and establishing Indian brands as frontrunners in sustainability efforts. Exporters are acutely aware that adherence to European Union regulations concerning chemicals and waste will soon dictate their access to the market.

Data focus

Textiles are among the top 10 industrial polluters in India (CPCB).

Tirupur knitwear units were shut down by court order for dumping untreated dye into the Noyyal River.

Ludhiana, Surat, Kanpur industries continue to discharge chemicals into rivers and groundwater.

India has 20 of the 30 most polluted cities in the world.

Nearly 40% of India’s rivers are too polluted for bathing. India ranks 105th of 125 countries on the Global Hunger Index.

If alternatives exist, why haven’t they scaled?

Research on Indian fashion firms shows the barriers clearly. Sustainable fabrics and waterless dyeing cost more, and small and medium manufacturers cannot absorb the expense. Pollution laws exist, but are poorly enforced. Recycling is technologically outdated: blended fabrics like poly-cotton are almost impossible to separate. Consumers, meanwhile, are addicted to cheap trends, fuelled by Instagram influencers, celebrity wardrobes, and the lure of constant novelty. The way forward needs three shifts.

1. Policymakers must frame a national circular textiles strategy with EPR mandates, stricter rules on water and chemical use, and incentives for clean technology.

2. Industry must move beyond token CSR, investing in transparent supply chains, credible reporting, and reverse logistics.

3. And consumers must rethink habits: buying fewer but better garments, repairing clothes, embracing thrift and rentals, and resisting the lure of endless refresh.

Fashion has always mirrored social change. In colonial India, khadi was a political symbol; today, slow and circular fashion must become an ecological one. The question is no longer whether to slow down fashion, but whether we can act fast enough before the damage becomes irreversible.

(The author is a doctoral researcher at Symbiosis International University, Pune, who is also working as a sustainability manager with a major fashion retailer in India.)

Published – October 11, 2025 02:40 pm IST