India is going through a rocky terrain as far as industrial production and corporate investment are concerned. On June 30, the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation (MoSPI) released the monthly growth rate of the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), which has slowed to a nine month low of 1.2%. This piece attempts to explain why industrial activity has not really picked up in any meaningful way since the COVID-19 pandemic.

To be fair, it is not as if the government has not tried. They have tried every trick in their book, starting with a significant corporate tax cut to the tune of eight percentage points in September 2019 (from 30% to 22%), then a significant capex-push over the last few budgets, and lastly an interest rate cut recommended by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) recently. The 2024-25 Economic Survey expressed its dismay by stating that “in terms of financial performance, the corporate sector has never had it so good … (but) (h)iring and compensation growth hardly kept up with it … Private sector GFCF in machinery and equipment and intellectual property products has grown cumulatively by only 35% in the four years to FY23, (which will) delay India’s quest to raise the manufacturing share of GDP, delay the improvement in India’s manufacturing competitiveness, and create only a smaller number of higher-quality formal jobs than otherwise.”

Determining investment

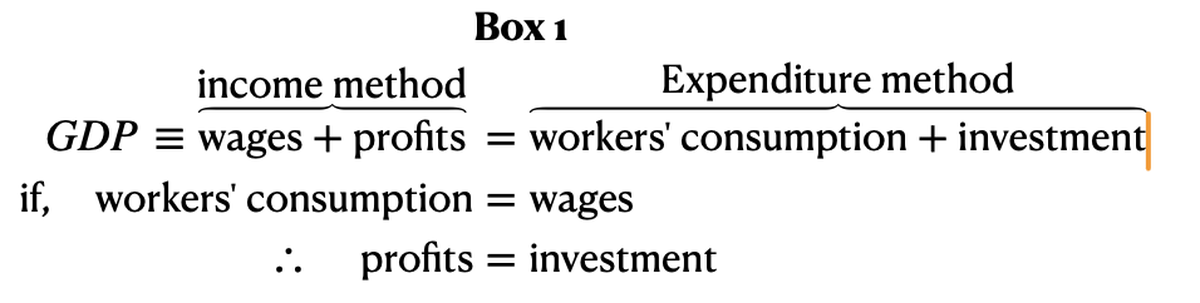

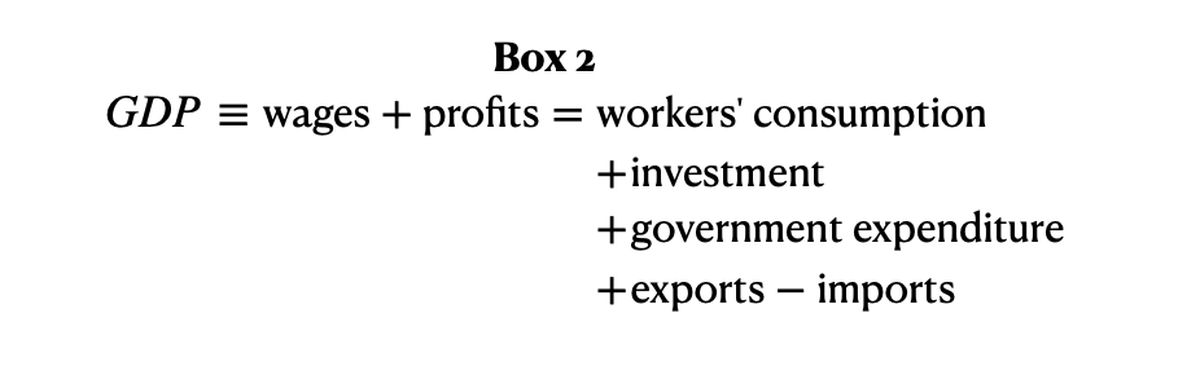

There is a famous debate between two Marxist scholars, Rosa Luxemburg and Tugan Baranovsky, on what determines investment in a capitalist economy which might be valuable to this discussion. To appreciate this debate and to understand the current predicaments of the Indian economy, we would like to present a basic representation of GDP and its determinants in a ‘pure’ capitalist economy, that is, one without any State intervention or access to external markets (see Box 1 for such a representation).

GDP can be measured in different ways. What we demand generates production in the economy, with the other side being the income generated for the producers. So, from the income side, the GDP is a sum of workers’ wages and capitalists’ profits and, from the expenditure/demand side, a sum of workers’ consumption and capitalists’ investment. The purpose of this piece is to explain the latter.

To get to the meat of the matter, we make a simplifying assumption that workers consume all their wages and capitalists do not consume at all (the argument does not change even if we remove this strict assumption). As Box 1 shows, wages and workers’ consumption cancel each other out. What we are left with are profits which must be equal to investment in such an economy. This equation, however, does not tell us whether profits cause investment or investment causes profits. This innocuous relationship has led to quite a debate in economics, which continues to this day.

To resolve this apparent chicken and egg problem, Kalecki, a Marxist economist asked a simple question: of the two, which one can the capitalists decide/control? ‘Capitalists may decide to … invest more in a given period than the preceding one, but they cannot decide to earn more.’ In other words, investment determines profits in a given period, not the other way round. But if this is the case, what is the limit to investment? Why can they not invest any amount they like? In fact, why should there be a problem of a lack of investment at all?

Baranovsky argued that there is no limit to investment provided a certain proportion is maintained between consumption and investment sectors. He went to the extent to say that investment decisions need not be tied to any final consumption demand. An economy where workers’ consumption is kept suppressed may still flourish with higher investment and higher profits simply by the decision of the capitalists to accumulate. Since capitalism and accumulation of capital is driven by profitability, investment provides the market for itself. Machines can produce machines to produce more machines.

However, Luxemburg countered by saying that while it’s true that investment leads to profits, it does not mean that any amount of investment will necessarily be undertaken. That would be a gross misreading of the relationship represented in Box 1. If the corporate sector were to collectively decide to invest, they would all be generating markets for each other, thereby, generating profits. But, unfortunately, investment decisions under capitalism are made by individual firms/capitalists and their decisions would be driven by their own assessment of demand for the products they produce. For example, in situations where the economy is not growing, it would be foolhardy for an individual capitalist to invest because adding capacity, when the existing factories are not running to capacity, would entail more losses. At the same time, if they were to invest collectively, the economy would have actually recovered. But coordinated or collectively planned investment is an anathema to capitalism.

Investment, first and foremost, depends on the demand for the goods (whether machinery, toys or cars) it produces. It does not, and cannot, have a life of its own. A pure capitalist economy, without exogenous stimuli, cannot provide an endogenous impetus for its own survival. It requires an exogenous stimulus to kickstart the cycle of more investment and profits. The situation is particularly grave when the economy is in a downturn/slowdown because demand is down. The only way there can be a turnaround is if there is a turnaround in demand itself.

The other factor behind investment is finance — internal (retained profits) or external (debt, public offerings etc).

Lagging corporate investment

The government assumed that with tax cuts and higher post-tax profits in the hands of the corporate sector, investment would pick up. But they have perhaps read the profit-investment causality wrong. Even others, who believe there can be an investment-led revival, miss the crucial point that Luxemburg was making. Investment will follow if there is a revival in process; it cannot lead the revival under conditions of slowdown. Investment cannot be made for the sake of investment. It requires the exogenous stimuli that Luxemburg was talking about. Where can that come from?

There are two such exogenous sources — government expenditure and external markets (see Box 2). With a slowing global demand, which is perhaps going to worsen with the ‘reciprocal’ tariff regime under U.S. President Trump, government expenditure is the most important lever to kickstart the investment cycle. But then has the government not done enough in the form of capex spending? Government indeed has spent but it has so far not succeeded as much as expected. Why?

The idea behind capex spending is that it would crowd-in private investment. This crowd-in could happen through a direct impact on investment as a result of better infrastructural facilities or by generating demand for goods produced by the corporate sector.

While there is no denying that there is a possibility of crowding-in, there are multiple factors at play here. First, the crowd-in of the first kind, which is through better infrastructure, may be delayed due to the gestation lags these big scale projects usually have. For example, a port takes time to build and become operational.

Second, while it is true that all such projects, whether big or small, create an immediate demand, how much of it is domestic demand and how much it is for economies outside depends on the import component of this spending. In other words, a part of this capex may be spent on imports, which simply cancels out without providing adequate domestic demand. Third, even how much domestic demand such a capex would generate depends on the labour intensity of these projects. If most of the money is spent on heavy duty machines, the employment generating capacity will be low, which translates to lower consumption demand.

As for the incentive to finance investment through lower interest rates or liquidity, both of which the RBI has been trying, it is like putting the cart before the horse. Capitalists would take loans only if they believe they will profit from such investment to pay the loans back. With sagging demand, low costs of finance is not enough. As Keynes had famously said, “whereas the weakening of either [speculative confidence or the state of credit] is enough to cause a collapse, recovery requires the revival of both.” This simple lesson needs to be learnt by both the RBI and the Finance Ministry if they want the economy to revive.

Rohit Azad and Indranil Chowdhury teach Economics at JNU and PGDAV College, Delhi University, respectively