‘Many migrants are not keen to shift their vote’

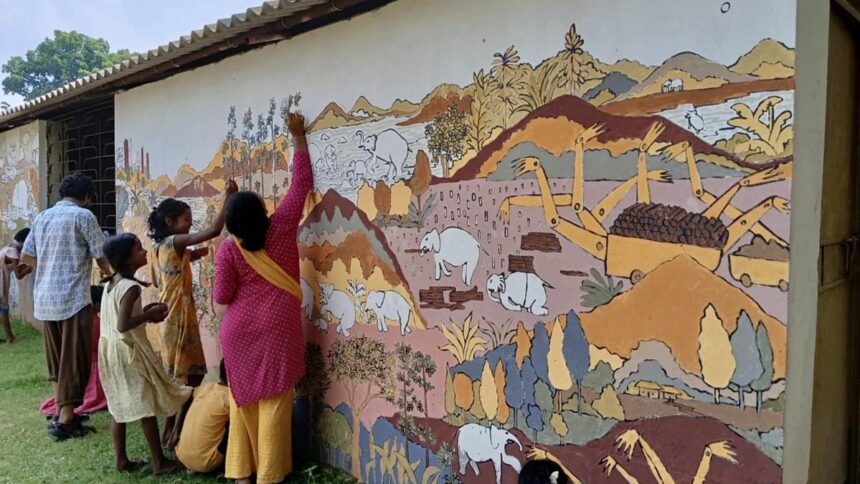

| Photo Credit: The Hindu

In the ‘Odyssey’, a major epic in Greek mythology, King Odysseus had to navigate between the dangers of Scylla, a monster residing in a rock, and Charybdis, a monster embodying deadly whirlpools. In the ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the Bihar electoral rolls initiated by the Election Commission of India (ECI), many migrant labour whose names have been dropped from the draft electoral roll are facing a similar predicament.

The term ‘ordinarily resident’

The electoral rolls are prepared by the ECI, as in the provisions of the Representation of the People (RP) Act, 1950. Section 19 of the RP Act requires that a person must be ‘ordinarily resident’ in a constituency for inclusion in its electoral roll. The requirement of being ‘ordinarily resident’ for inclusion in the electoral roll is to ensure that the voter maintains real ties with the constituency that preserves representative accountability. It is also aimed at preventing fraudulent registrations.

Section 20 provides the meaning of the term ‘ordinarily resident’. It specifies that a person shall not be deemed to be ‘ordinarily resident’ in a constituency only because he/she owns or possesses a dwelling house therein. However, a person temporarily absent from his/her place of residence shall continue to be ‘ordinarily resident’ therein. Section 20A was added in 2010 to enable Non-Resident Indians who have moved out of India even for the long term, to register and vote in the constituency in which their address given in the passport is located.

The ECI has classified electors who were not found in their residence or did not submit the enumeration forms as part of the SIR process as ‘permanently shifted/not found’ and excluded them from the draft electoral roll.

Article 19(1)(e) of the Constitution guarantees every citizen a fundamental right to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India. It follows that any citizen has the right to shift his/her vote to their new place of residence anywhere in India if they so desire.

The issue arises in respect of migrant labourers. The Periodic Labour Force Survey of 2020-21 estimated that around 11% of India’s population migrated due to employment-related reasons. This translates to close to 15 crore voters being migrant labour within or outside their States. Most labourers, short-term or long-term, migrate due to the lack of opportunities in their region. Many migrant construction and security workers also migrate alone (without family). They live in temporary shacks/residences at their place of work and move from one location to another, within a State or even in different States, as part of their work. They return to their home State at regular intervals and exercise their right to vote from the place where their families live and properties exist.

The Gauhati High Court, in Election Commission Of India & Anr vs Dr. Manmohan Singh & Ors (1999), indicated that the term ‘ordinarily resident’ shall mean a habitual resident of that place. It must be permanent in character and not temporary or casual. It must be a place where the person has the intention of dwelling there permanently. A reasonable man must accept him/her as a resident of that place. While migrant labourers may not be residing permanently in their native constituency, the philosophy behind being ‘ordinarily resident’ — in the opinion of the courts — is broadly fulfilled with respect to that residence for such migrant workers.

Legality versus realpolitik

The ECI maintains that under the RP Act, migrants who have shifted out of their native State/constituency can register as an elector in their new place of residence. Many migrants are anyway not keen to shift their vote. They may not have any document other than an Aadhaar card in their new place of residence (which is not in the list of eligible documents for fresh voter registration under the SIR process). Further, it can be challenged whether they fulfil the conditions of being ‘ordinarily resident’, as laid down by the courts, with respect to the new residence.

Keeping those legal arguments aside, the political issues on the ground in the in-migration States that they reside in cannot be overlooked. Regional political parties in such States have already begun raising issues about the possible inclusion of migrants in the electoral roll of their States. They object to it on the ground that this would vitiate the democratic process since these migrant labourers are not permanent settlers in their States.

They argue that migrants do not understand the political issues in their States and, hence, should not be allowed to vote in these elections. While it may be argued that migrants can be included in the rolls of in-migration States de jure, it could potentially result in their de facto disenfranchisement due to the social and political issues in their place of work. The Supreme Court of India should take these factors into consideration while passing its orders in the cases linked to the SIR.

Towards a fair and inclusive process

In India we accept election results where almost 50% voters in many metropolises do not step out of their houses to vote in booths which are less than 500 metres from their residence. Most non-resident Indians, who have the right to vote, do not exercise their franchise as they are unable to come to their constituency on the day of elections.

While these arguments can be made for the case of inclusion of migrant labourers in their original place of residence, it cannot be an alibi for the lack of their participation in elections. Steps such as ensuring strict enforcement of statutory holiday on the day of polling as well as the running of more special buses and trains can effectively increase the participation of migrants in the electoral process within a State. With respect to inter-State migrant voters, the ECI had developed a pilot of Multi Constituency Remote Electronic Voting Machine (RVM) that could handle up to 72 constituencies. It had planned a demonstration of the same to recognised political parties in January 2023. However, this was short lived following concerns raised by political parties as well as administrative challenges. With the advent of newer technologies, robust and secure methods (acceptable to all stakeholders), for remote voting should be feasible. Until this happens, steps such as enabling more train and other transportation services as well as incentives for a few additional days of paid leave for travel can be explored to ensure more electoral participation by migrant voters.

Why has Bihar’s SIR caused a stir in Tamil Nadu?

Parliament, which represents the will of the people, should also consider suitable amendments to the RP Act to preserve the choice of migrant labourers with respect to their place of voting.

Rangarajan R. is a former IAS officer and the author of Courseware on Polity Simplified. He currently trains at Officers IAS Academy. The views expressed are personal

Published – August 08, 2025 12:16 am IST