The recently released report by Lokniti-CSDS provides a data-driven analysis of digital platforms’ role in 2024 elections, showing how they complemented traditional door-to-door efforts in mobilising voters. This is Part 2 of the study.

Campaign songs are increasingly vital tools for political communication, offering a catchy and accessible medium to amplify candidates’ messages and mobilise voters. This study analysed 150 YouTube campaign songs — 80 supporting the Congress and 70 the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — uploaded between January 1 and April 10, 2024. These two parties were selected due to their nationwide presence and high digital output. Songs were chosen through stratified sampling from a master list created via keyword-based YouTube searches. Sampling was done from different sources: official party channels, candidates’ channels, and independent supporter channels, with attention to diversity in engagement levels and channel size. Songs were manually coded using a structured codebook covering themes, tone, references, mobilisation cues, and production styles. Most songs were sourced from independent channels (89% for INC, 81% for BJP), with fewer uploads from official party or candidate accounts. This methodology allowed the study to analyse both official messaging and grassroots, decentralised narratives, including more fringe or extreme perspectives, especially with respect to content from the BJP’s supporter base.

BJP songs centred on Prime Minister Modi, projecting trust and continuity. Religious references (“Ram,” “temple,” “saffron”) underscored Hindutva appeals, particularly around the Ram Temple. Nationalist themes were prominent, with terms such as “Bharat Mata,” “Kashmir,” and “enemy” being commonly used. Economic themes appeared via words like “guarantee,” “farmer,” and “poor,” while “victory” and “wave” conveyed momentum and confidence. The Congress’s songs highlighted leadership through frequent mentions of “Gandhi,” “Rahul,” and “Priyanka.” Core themes included justice, rights, and systemic change, signalling a focus on equity. Words like “hope” and “save country” framed the campaign as reformist.

Catch-phrases and narratives

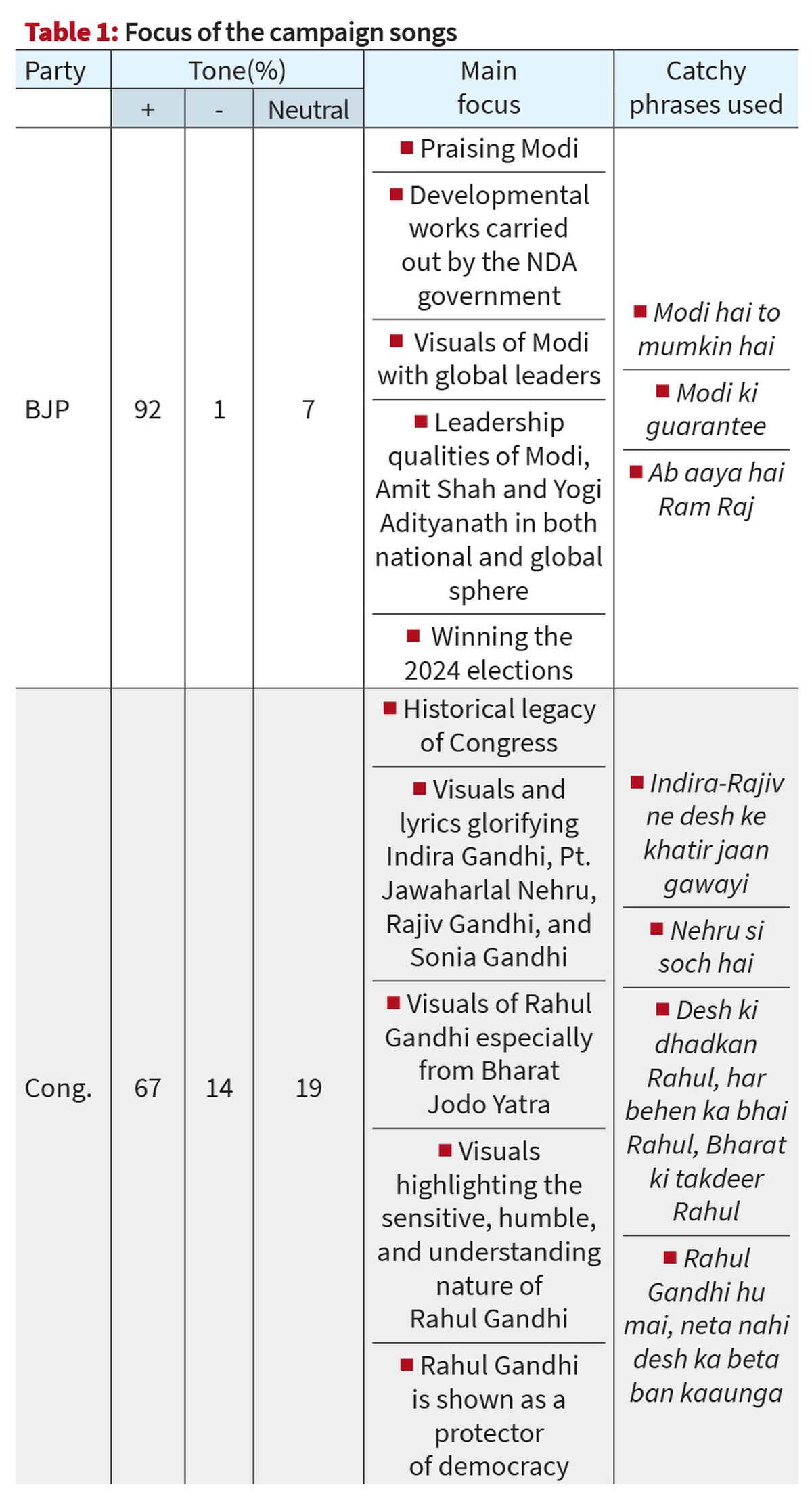

A lyrical and word cloud analysis reveals distinct strategies by the BJP and Congress. BJP songs focused on Mr. Modi, with slogans like “Modi hai to mumkin hai”, “Modi ki guarantee”, and “Aayega to Modi hi” linking him to progress and stability. Direct attacks on opponents were rare (Table 1).

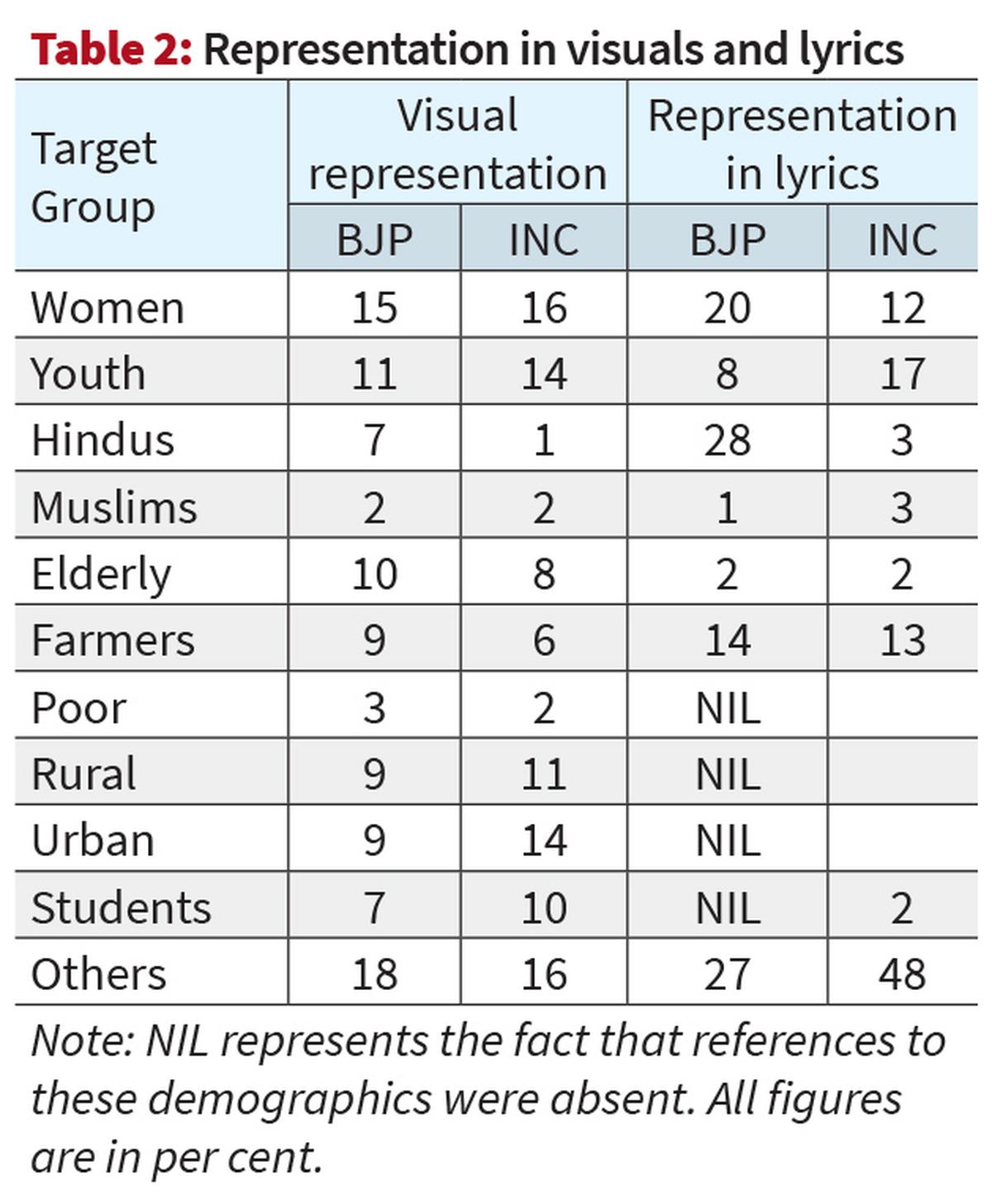

Congress songs highlighted Rahul Gandhi and the party’s legacy with phrases like “Desh ki dhadkan Rahul” and “Nehru si soch hai”, portraying him as a modern visionary. Emotional appeals referencing sacrifice, such as “Indira-Rajiv ne jaan gawayi”, sought to inspire loyalty and continuity. Unlike BJP, Congress songs contained direct criticism, with lines like “Loktantra ka bhediya” and “Jhutho se desh bachana hai”, framing the ruling party as a threat to democracy. Both the BJP and the Congress employed campaign songs to engage key voter groups, emphasising distinct priorities. BJP’s lyrics highlighted Hindu identity, women, and farmers, whereas Congress focused more on youth, women, and minority inclusion. Visual content reinforced these themes, with Congress giving greater prominence to urban, rural, and student populations (Table 2).

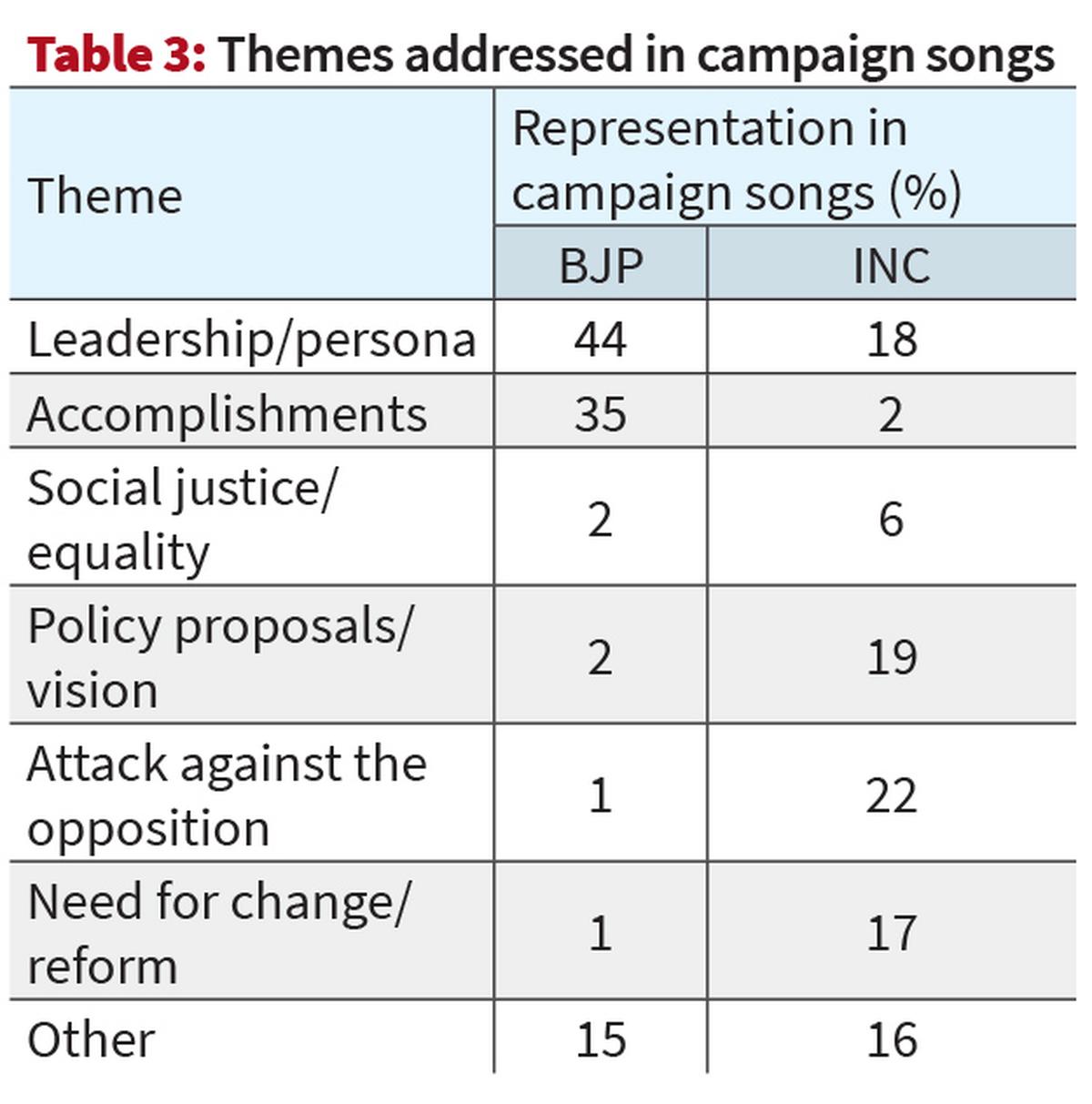

Moreover, BJP songs heavily highlighted past achievements (35%), showcasing governance successes, while the Congress focused on future promises and reforms (Table 3).

Calls for change (17%) and themes of social justice (6%) appeared more prominently in Congress’s messaging, aligning with its opposition role. Congress also directly critiqued the ruling party in 22% of its songs; BJP rarely engaged in this (1%).

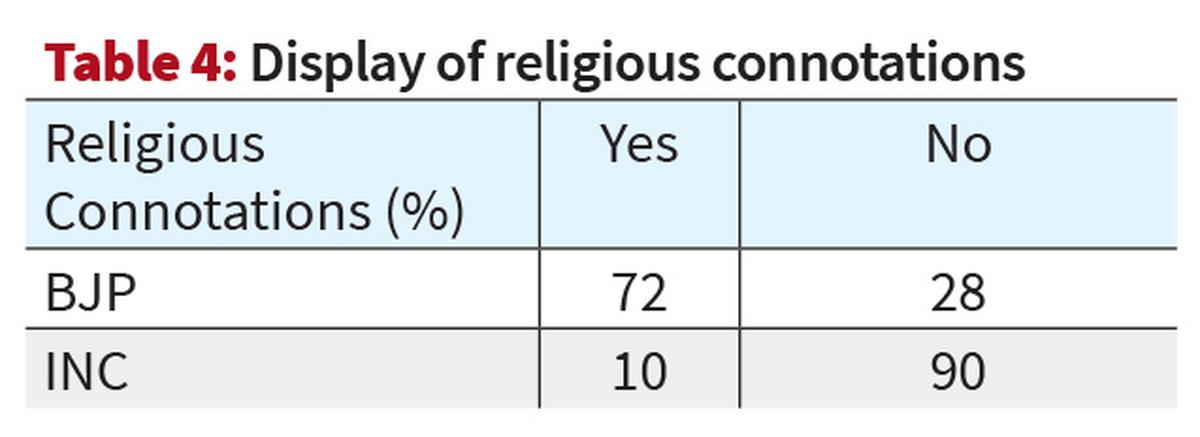

Religious connotations were prominent in BJP’s songs (72%), reflecting Hindu nationalist themes and featuring symbolic references to Ram Mandir and slogans such as “Jai Shree Ram.” Unofficial songs were more overtly communal. In contrast, only 10% of Congress songs contained religious themes, reflecting a more pluralistic communication style (Table 4).

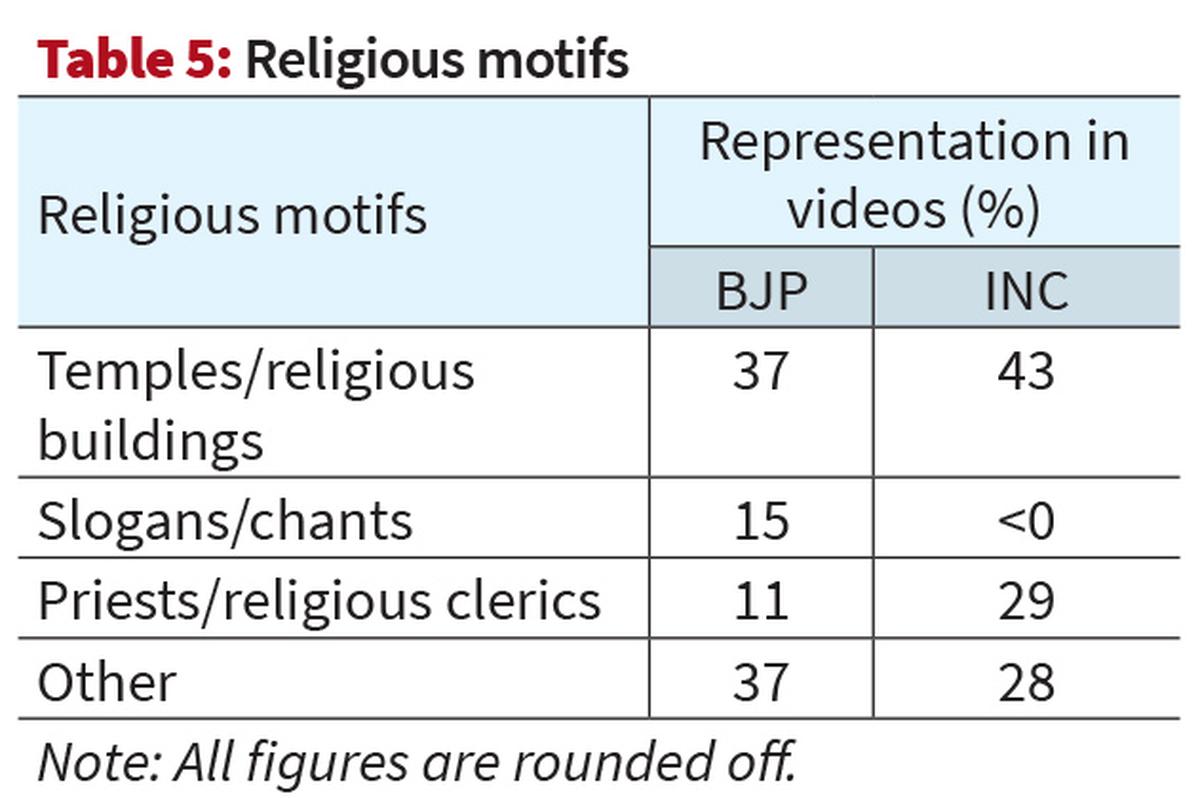

While BJP’s religious messaging was largely rhetorical, the Congress leaned more on visual representation. Religious imagery appeared in 43% of the Congress’s videos compared to 37% of the BJP’s. The Congress also featured religious clerics more prominently (29% versus BJP’s 11%), signalling efforts to engage multiple faith communities (Table 5).

On third-party campaigners

Third-party campaigners, including individuals, political consultancies, and advocacy groups, have gained significant influence in the digital age, shaping electoral dynamics through targeted advertisements on platforms like Meta (formerly Facebook). These entities, which do not field candidates, often campaign for or against specific parties, candidates, or issues. In India, third-party campaigners invest heavily in digital ads, sometimes bypassing political finance and content regulations. This unregulated spending raises concerns about transparency and accountability, suggesting potential collusion with political parties. Their growing role underscores the need for stronger oversight in modern electoral campaigns.

The Lokniti-CSDS study focuses on digital campaigning by third-party advertisers on Meta (formerly Facebook) during the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. Conducted over the critical months of April and May 2024, the study also focused on identifying the top 50 highest spenders on Meta, with 31 of them being third-party advertisers. This analysis delves into the role of these entities in shaping electoral narratives through digital ads, shedding light on their influence and spending patterns. The advertising expenditure of these third-party campaigners ranged from ₹0.6 million to ₹73 million during the study period. The analysis covers 1,114 randomly selected ads from 31 campaigners to assess their digital strategies, independent of any party or candidate endorsements.

Third-party campaigners on Meta used catchy and provocative names to attract attention, such as “Mahathugbandhan,” which critiques the INDI Alliance, and “Hirak Rani Bye Bye,” which portrayed Mamata Banerjee as a dictator, inspired by the film Hirak Rajar Deshe. These creative names were part of a broader strategy to influence public perception. The Meta Ad Library reveals the financial backers behind these campaigns, which includes entities like the Populus Empowerment Network and Vyuhah Consulting. Some political parties, like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and the Congress, have been found funding third-party advertisers, raising concerns about transparency and the potential for circumventing expenditure limits. The lack of detailed funding information in the Meta Ad Library complicates accountability, creating avenues for unregulated influence in the electoral process (Table 6).

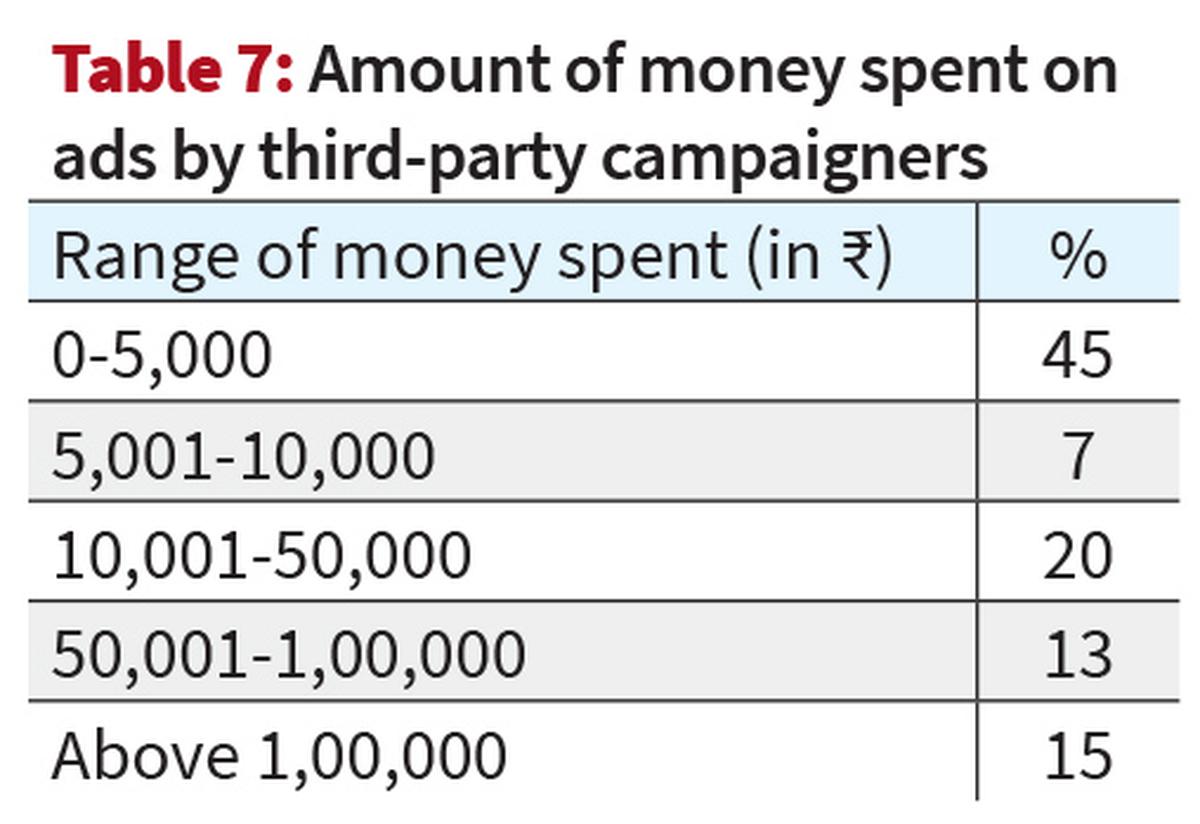

An analysis of the ads posted by the 31 third-party campaigners revealed a wide variation in spending, ranging from under ₹5,000 to over ₹1,00,000 per ad. The majority (72%) of the ads had expenditures capped at ₹50,000, while 28% exceeded this amount (Table 7).

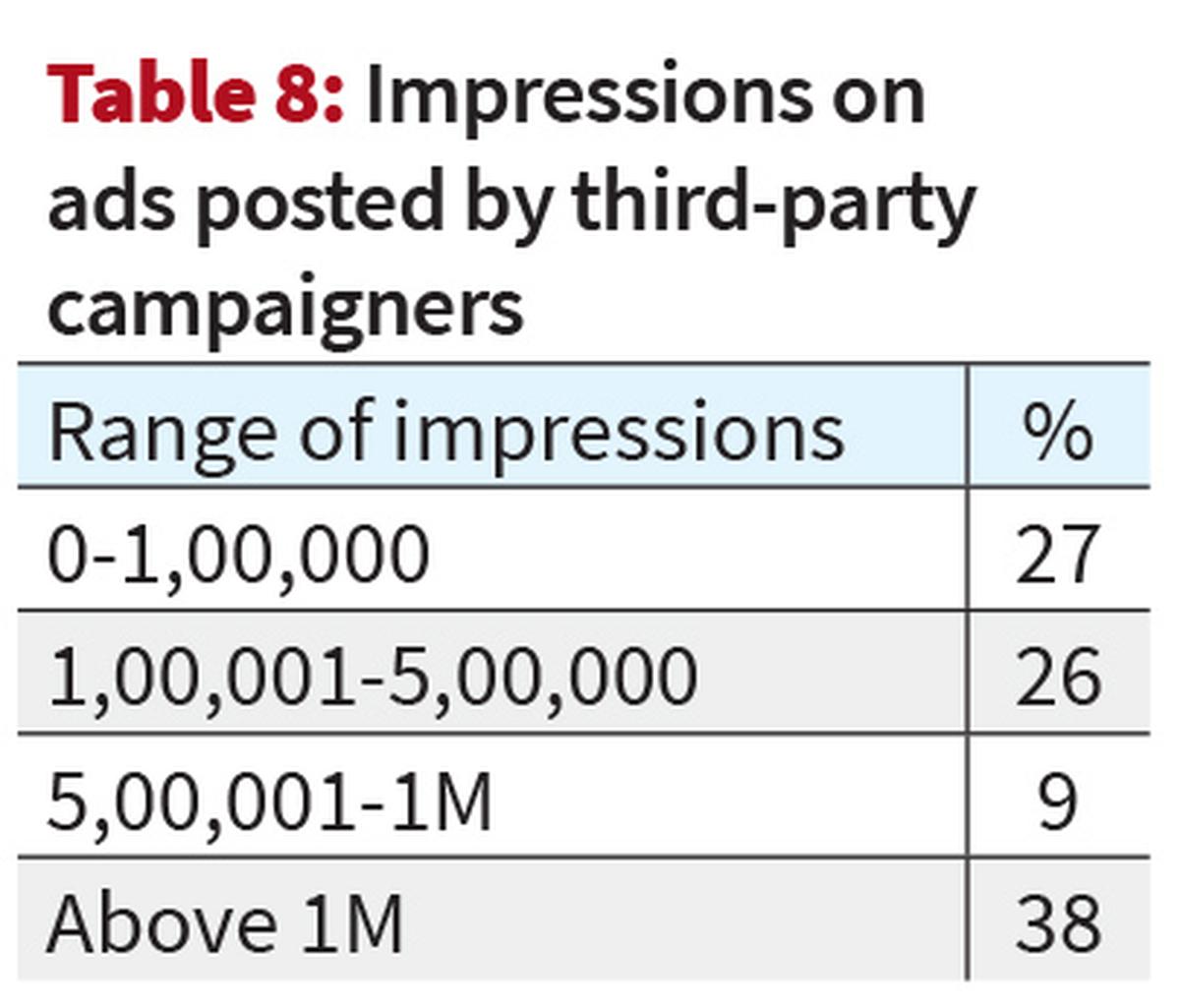

In terms of engagement, impressions reflecting how often an ad appeared on a screen served as a key metric. Interestingly, 53% of ads received up to 5,00,000 impressions, while the remaining 47% surpassed 5,00,000 impressions. This highlights the significant reach and potential impact of these third-party campaign ads (Table 8).

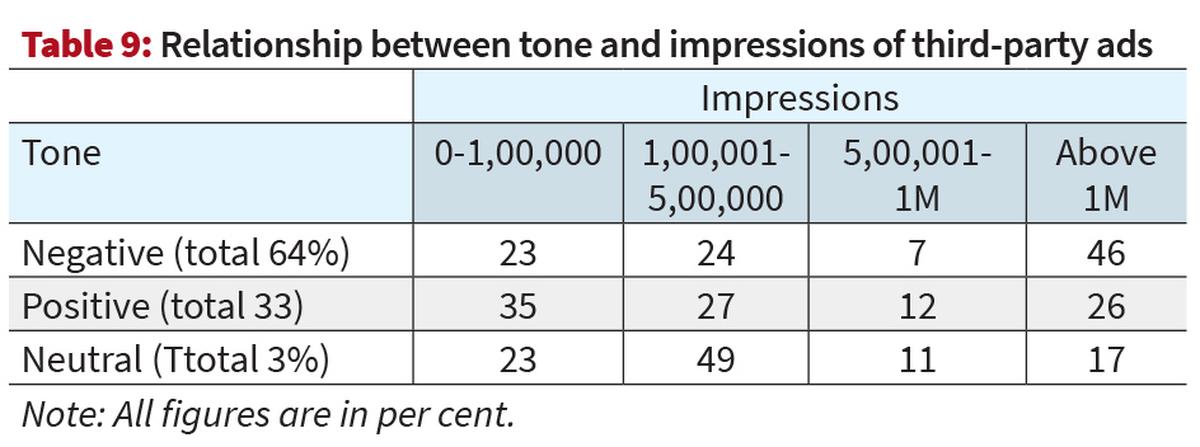

Thematic analysis of third-party campaign advertisements reveals a wide range of strategies, with key themes emerging across content. A major focus was criticism aimed at opposition parties, their leaders, and their supporters. Religious themes were also prominent, with ads either accusing parties of being anti-Hindu or praising them for supporting Sanatan Dharma. The most concerning ads included misinformation and Islamophobic content, using derogatory language and divisive tactics to sway voter sentiment. This analysis reveals a clear trend — majority of third-party ads carried a negative tone, with these ads typically having higher spending compared to positive or neutral ones. In fact, 46% of the negative tone ads achieved impressions exceeding one million, compared to just 26% for positive ads, demonstrating that negative content has a far greater reach and impact (Table 9).

Furthermore, negative advertisements were particularly effective among younger audiences, with 83% of these ads being consumed by individuals aged 18-34.

Third-party advertisements, often marked by negative tones and problematic content, have raised serious concerns. These ads frequently used inflammatory captions such as “Bengali Muslims, will they make Bengal Bangladesh?” and derogatory terms like “Babur ki Santaan” directed at Muslims. Political leaders were also targets of such ads, with Rahul Gandhi being called “Makkar” and Mamata Banerjee depicted as hiding behind terrorist groups like ISIS. Misinformation was rampant, and some ads even alleged external interference in Indian elections by figures like George Soros. This highlights the urgent need for stricter regulation of third-party advertisers, focusing not just on content but also on the sources of their funding and affiliations with political parties. Such measures are necessary to ensure transparency, fairness, and to protect the integrity of the democratic process.

On social media influencers

Social media has become a powerful platform for political expression, with individuals sharing views on key issues and events. Social Media Influencers (SMIs) have emerged as key figures in this landscape. These individuals, with large followings, can shape public opinion by sharing content that resonates with their audience. Unlike traditional media, SMIs maintain independence, enhancing their credibility. This study analysed 30 SMIs active between January and June 2024, and divided them into two groups — Critical Social Media Influencers (CSMIs), who critique the government, and Supportive Social Media Influencers (SSMIs), who endorse the government. The selected SMIs were categorised based on their follower count: two influencers had 50,000-99,999 followers, nine had between 1,00,000-4,99,999 followers, and five had 5,00,000-9,99,999 followers. The sample also included eight influencers with 1-2 million followers, and six influencers with over 2 million followers (Table 10).

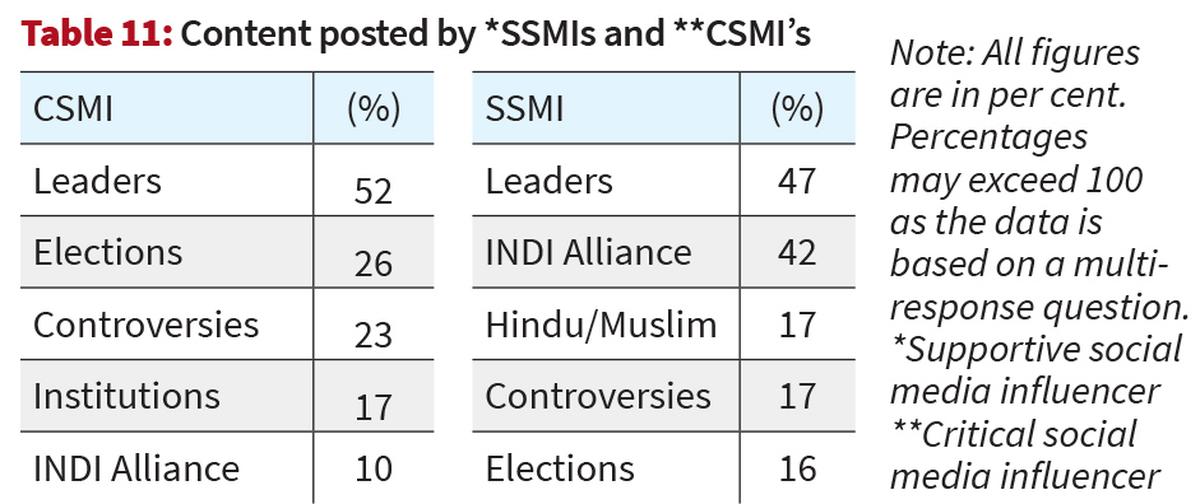

During the analysis period, 83% of CSMIs and 81% of SSMIs posted more than 10 political posts per month. Among CSMIs, 3% of content was paid for, compared to 4% among SSMIs. This indicates that the vast majority of political content produced by both groups was organic rather than financially supported. The political content shared by SMIs covered a range of topics. CSMIs primarily focused on political leaders (52%), followed by 26% discussing elections, and 23% on ongoing controversies. SSMIs concentrated on political leaders (47%) and the INDI alliance (42%) (Table 11).

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections underscored a significant evolution in India’s digital campaigning, bringing both sophistication and new challenges to electoral transparency. The growing complexity of digital campaigning, encompassing scaled personalisation, cross-platform messaging, and third-party influence has exposed systemic gaps in current regulations. Without urgent reforms to address real-time transparency, platform accountability, and the evolving role of third-party actors, the integrity of India’s electoral system could be compromised. It is essential to implement measures that address the challenges posed by a digitalised electoral environment.

The team comprised Sanjay Kumar (Professor and Co-director Lokniti-CSDS); Suhas Palshikar (Taught political science and is chief editor of Studies in Indian Politics), Sandeep Shastri (Director-Academics, NITTE Education Trust and the National Coordinator of the Lokniti Network), Aditi Singh (Assistant Professor, Jindal Global Law School, O.P. Jindal Global University) and Vibha Attri (Research Associate at Lokniti-CSDS).