India and its vibrant aesthetic are everywhere right now. From the V&A’s nod to Indian royalty in its Cartier show, to design fairs such as PAD (Pavilion of Art and Design), TEFAF (The European Fine Art Foundation) and Frieze, where Indian art, jewellery and design have a stronghold. In department stores — Harrods, Selfridges, Bergdorf Goodman — brands such as Sabyasachi High Jewellery, Kartik Research and Lovebirds sit alongside global names. And on runways, India’s presence is no longer peripheral, it’s pivotal.

It’s no secret that the world wants a slice of the Indian pie. With a luxury market currently valued at $17 billion and projected to triple by 2030, an affluent Gen Z cohort 377 million strong, and increasing cultural capital, India is drawing global attention. Dior’s Fall 2023 show in Mumbai may well have been the tipping point. That moment which was widely Instagrammed, editorialised, and held up as a turning point, set a new template for how the country could be platformed. The set was quite literally India: the Gateway of India as backdrop, the clothes — woven Madras checks and draped lungi-style skirts — were crafted by Chanakya School of Craft (a longtime collaborator, having embroidered the mise-en-scene at most of Dior’s shows under creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri’s helm), and a musical score that paid homage to Indian classical traditions.

Dior’s Fall 2023 show in Mumbai

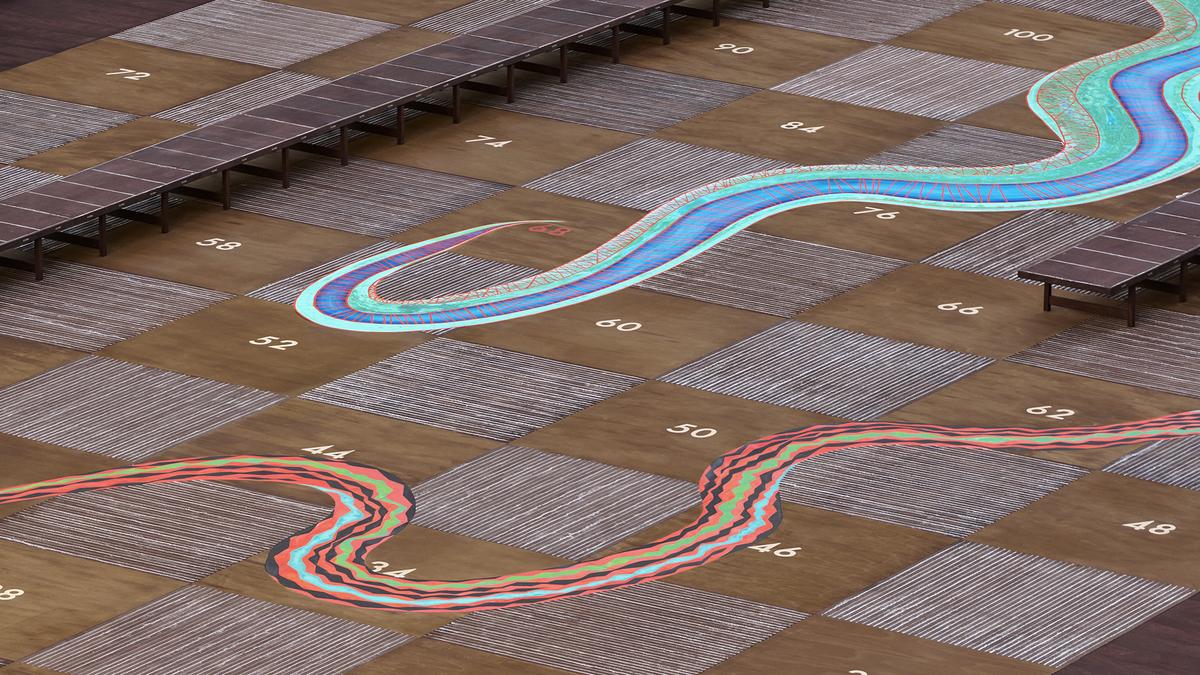

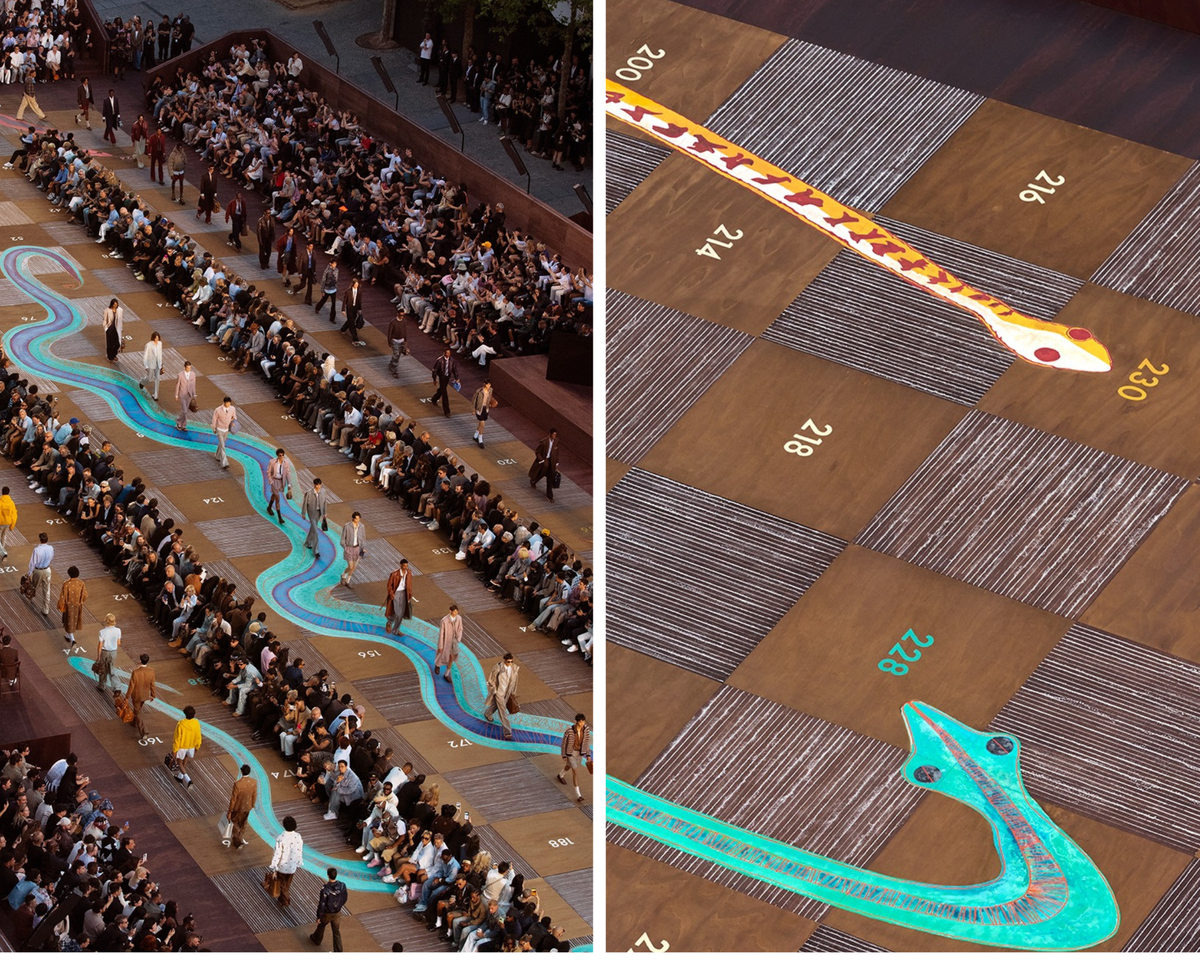

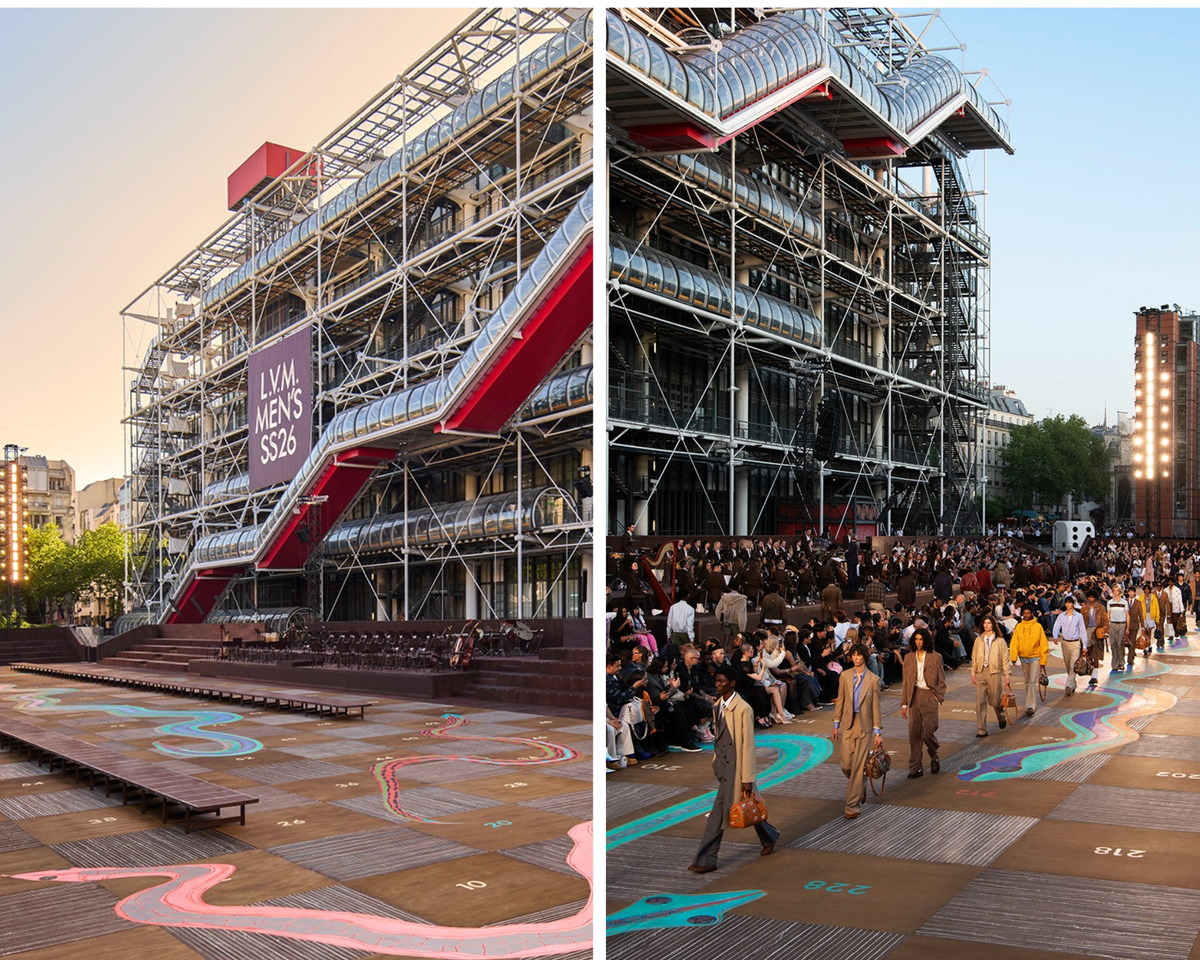

Last month in Paris, as guests at the Louis Vuitton menswear show took their seats before a 2,700 sq.m. set designed by architect Bijoy Jain and his Studio Mumbai, inspired by the ancient Indian game of snakes and ladders, it felt like a signal of continuity: that India is not just momentary inspiration but a sustained presence in luxury’s imagination. The show by creative director Pharrell Williams featured rickshaw-shaped bags, trunks, sneakers and jackets with a smattering of embroideries from India, and a soundtrack by Oscar-winning composer A.R. Rahman.

Louis Vuitton x Bijoy Jain’s snakes and ladder set for the Spring-Summer 2026 menswear collection

Cultures as trend

Just a week earlier, at Milan Fashion Week, Prada sent models down the runway in Kolhapuris (those hardback quotidian leather sandals local to Maharashtra) paired with shorts and T-shirts, and with design details of the humble footwear also seen on rings, and facings of leather jackets. What followed was an avalanche of pushback and adoration, in equal measure, from the South Asian corner of the Internet. Who made the Kolhapuris? Why weren’t they credited? Why the silence? Why now?

A model presents a creation from Prada’s Spring-Summer 2026 menswear collection

| Photo Credit:

Reuters

In contrast, the Louis Vuitton show was celebrated: this is how collaboration should be done. Visionary. Complete.

And yet, beyond the headlines and viral takes, the question persists: what now? How can this cultural bridge, tentatively being built between India and the world, move from moment to movement?

“Everybody celebrates that Louis Vuitton has done this, Prada has done that. But sadly, it doesn’t have any real impact on the business of fashion,” says Maximiliano Modesti, the French-Italian founder of Les Ateliers 2M, an India-based craft and embroidery studio that works with global luxury houses, including Chanel and Hermès. “Craft is soft power,” he explains. “If this level of craft were available in a European country, or even China, it would have been used to build a cultural and economic empire by now.” But for decades, that power was extracted rather than credited — India’s artisans fuelling couture and ready-to-wear from Paris to New York, often without a label, voice or seat at the table.

Maximiliano Modesti

| Photo Credit:

Abhay Maskara

Still, progress is being made. Modesti credits private players in India such as Sangita Jindal, who launched the Jindal Craft Prize, Nita Ambani’s work with Swadesh (a platform for artisans), and artist-entrepreneur Anita Lal’s newly launched Good Earth Foundation, as key to preserving and promoting heritage. Says Modesti, “In India, you always need private initiative to counterbalance the lack of political will. It’s been true of education, healthcare, and now finally, craft and design.”

Even so, Modesti’s wary of fashion’s tendency to cycle through cultures as trends. “One season it’s India, the next it could be Africa. It’s always India seen through a historical prism. But if you know what’s happening now with Indian architects, designers, creatives — the Indian scene is flamboyant.”

Fashion photographer Rid Burman agrees. “There’s so much more than what gets shown globally. Brands latch onto palaces and Bollywood, but India also has arthouse cinema, a thriving art scene, classical and contemporary music. There’s a huge cultural backbone that’s being overlooked,” he says.

So far, Indian aesthetics have largely been filtered through a western gaze. The opportunity ahead is in letting Indian creators tell the story on their own terms.

Looking beyond the palaces

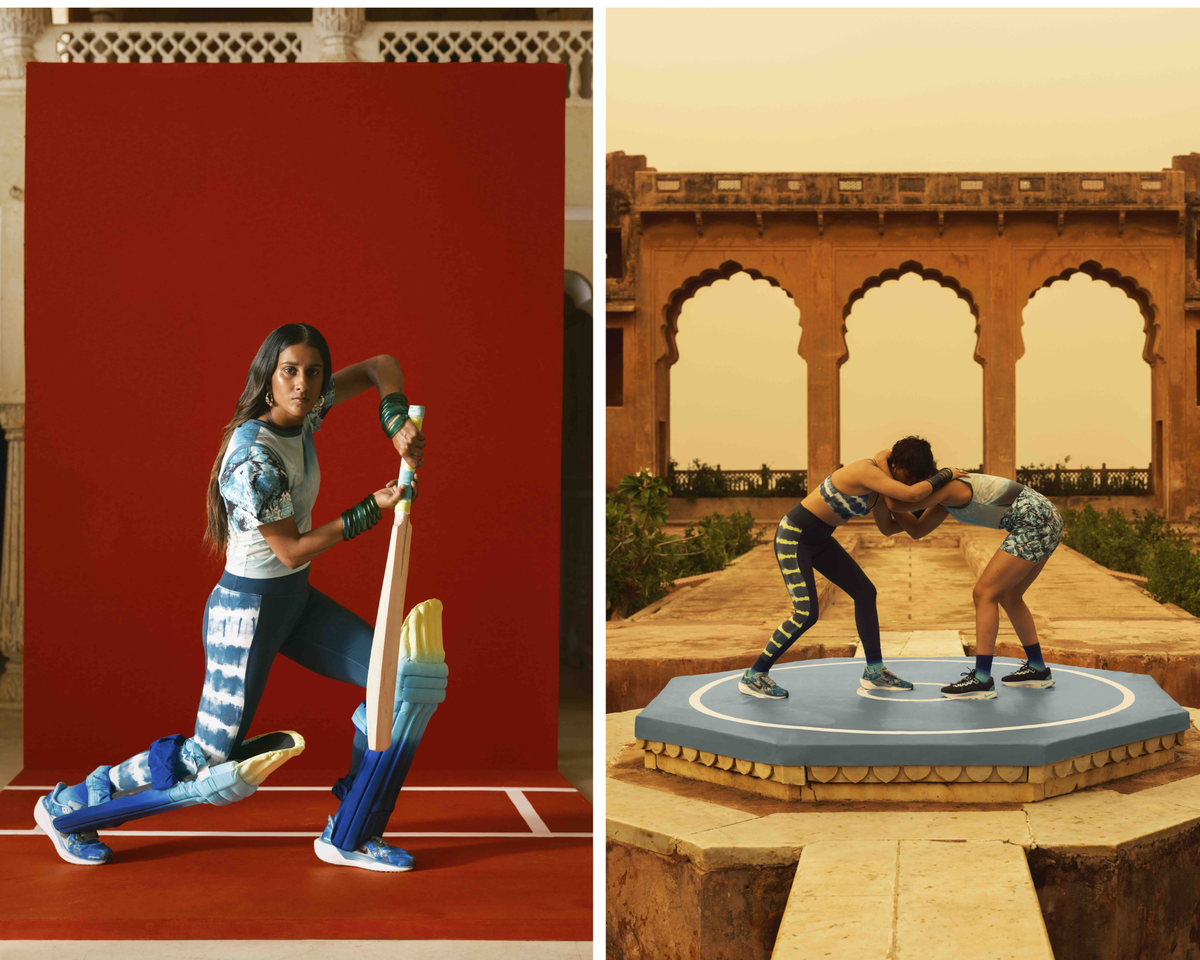

One promising counterpoint to this historical pattern is the Nike x NorBlack NorWhite collaboration. More than just applying Indian motifs to global streetwear, the campaign was conceived, led and styled locally. Founders Mriga Kapadiya and Amrit Kumar — who returned to India from Toronto to start the label — cast Indian female athletes, directed the shoot, and shaped the narrative. The result was vibrant, modern, and self-assured.

The Nike x NorBlack NorWhite collaboration

Designer Kartik Kumra’s label Kartik Research — worn by the likes of Kendrick Lamar, Stephen Curry, Brad Pitt and Riz Ahmed — is one of the sharpest expressions of Indian craft meeting contemporary design. Built on techniques such as bandhani and kantha, the brand has shown in Paris and is stocked by retailers from London to New York. Production is anchored in India, with a strong focus on small-batch making and local material sourcing.

Last year, Kumra published How to Make it in India — a zine-meets-manifesto that argues for defining success on one’s own terms. His multilingual approach — visually, culturally and commercially — is rewriting the rulebook on how India can show up on the global stage: not by conforming, but by leading with its own terms and textures. “I’m definitely aware of the connotations [India has], but I think the idea is to not be very on the nose with the referencing,” says Kumra. “It’s always a tricky balance; leaning into heritage but avoiding being too literal. Hopefully, the conversation around Indian culture globally can pivot from being overly nostalgic or stuck in its ways into something more generative or weirdly futuristic.”

Designs from Kartik Kumra’s label Kartik Research

In jewellery, Maison Aneka is reframing what Indian design can mean. “We want to show what a rooted-yet-modern India looks like,” says CEO Ankit Mehta. With design teams based in Mumbai and Paris, and a boutique on Place Vendôme, flanked by Schiaparelli, Van Cleef & Arpels, and Boucheron, as well as in Printemps and Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda, Aneka’s pieces reflect a cosmopolitan ethos. “Honestly, most people I’ve met don’t know what ‘Indian jewellery’ looks like. They have vague visuals of palaces, elephants, heritage. But the India of today hasn’t yet been defined for them,” he adds.

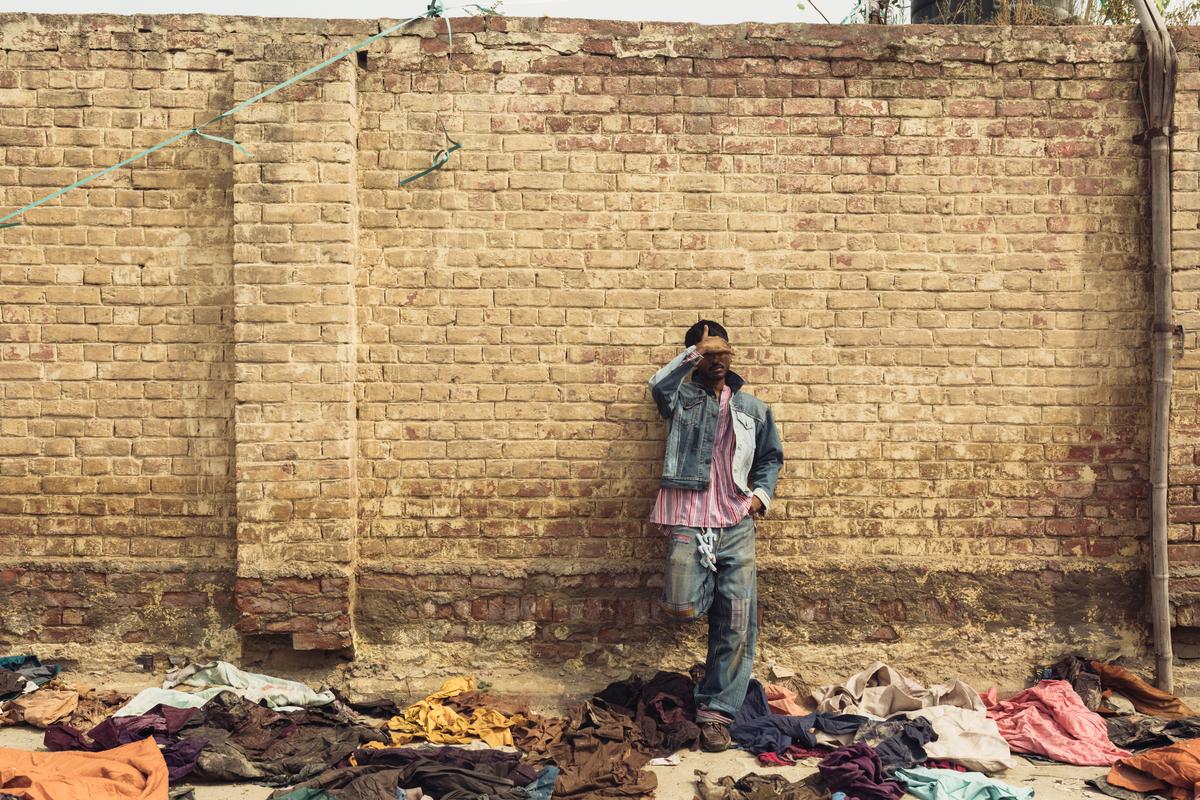

Designer Ritwik Khanna of Rkive City, known for his circular fashion practice, was one of a handful of South Asians invited to Louis Vuitton’s Paris show. He met Williams at a Vogue India lunch earlier in the year and shared his work. “India is no longer just a textile or embroidery country — it’s an innovations country,” he says. “If someone from India creates something relevant, efficient, and of high global quality, there’s no way to side-eye that.”

Designer Ritwik Khanna

| Photo Credit:

Abyinaav

A Rkive City campaign

| Photo Credit:

Arvaan Kumar

Will the next luxury brand be from India?

For product designer and entrepreneur Vikram Goyal, the ambition is to shift India’s identity from supplier to storyteller. His work, often shown at PAD London (this year will mark his third in collaboration with Milan’s Nilufar Gallery), and a recent collaboration with luxury brand de Gournay that translated his repoussé brass murals into hand-painted wallpapers, is steeped in Indian craft but shaped for a global audience. A large-scale mural is also in the works for Design Miami later this year. “There’s this general trend towards celebrating the handmade and the artisanal across disciplines. People are saying, ‘this is fresh, this is new’,” he shares. “There is no other country in the world with so much craft, cultural narrative and storytelling as there is in India. And for those stories to be told in a contemporary, intelligent way has been a joy for us.”

In fine art, too, the lens is widening. “There’s a lot more interest coming from institutions, curators, collectors,” says Roshini Vadehra, director of New Delhi-based Vadehra Art Gallery. “South Asian artists aren’t speaking in narrow, regional voices. Whether it’s gender politics or geopolitics, the themes are global.” Earlier this year, Vadehra played a key role in facilitating the Serpentine Gallery’s landmark retrospective of modernist painter Arpita Singh — marking the first major solo exhibition of an Indian artist at the institution in over a decade.

Roshini Vadehra

The gallery worked closely with Singh’s family and studio, and was instrumental in securing loans and shaping the narrative of the show. At Frieze London this October, the gallery will present an all-women showcase from across the subcontinent and diaspora — a reflection, she says, of a more interconnected, nuanced voice emerging from the region.

Artist Himali Singh Soin at Tate Britain

| Photo Credit:

Fiona Hanson

Designer Nimish Shah, founder of Shift, draws a parallel with Japan’s rise in the 1970s, when brands such as Comme des Garçons and Issey Miyake reframed Japanese craft into avant-garde fashion. “It elevated Japan from being a traditional supplier to the source of some of the edgiest designs. That’s where India is headed.”

Back in 1998, Modesti pushed brands like Isabel Marant to begin labelling their pieces Made in India. “She was the only one who listened,” he recalls. Hermès, too, has included the label on every scarf, cashmere and carpet produced by Les Ateliers 2M since 2005. But there is work to be done. Government intervention, specifically. When that is achieved, he says, “The next luxury brands will be born from India. Will it be Sabyasachi? Or someone entirely new? I don’t know. But it will happen.”

Khanna agrees. “The only shows I’ve ever seen in my life have celebrated India,” he says, recalling Dior’s Mumbai show (which he admits to “sneaking into”) and Louis Vuitton’s Paris production. “Today, when kids hear that Kartik Kumra is a semi-finalist in the LVMH Prize, or that Bijoy Jain did the LV set, they grow up thinking they belong on the global stage. That they are entitled to be a part of all this equally.”

The question is no longer whether the world is watching India. It is whether India can build the creative and structural infrastructure to make this attention lasting — and entirely its own.

The writer is an independent journalist based in London, writing on fashion, luxury and lifestyle.