Recent observations on the rules-based international order have suggested that this system of interlocking governance institutions that emerged since the end of World War II, known to some as Pax Americana, might survive or thrive despite the onslaught of political and economic confrontations foisted on the world by U.S. President Donald Trump. The real question is not about its survivability per se, but rather the extent to which it might mutate under pressure from Washington’s coercive policy prescriptions inflicted upon developing and emerging economies, particularly across the Asian region.

A few definitional remarks are in order at this point. Firstly, the rules-based international order, a liberal paradigm seen as a remedy to the devastation wreaked by the two World Wars, was brought into existence by the U.S. This was made possible by the U.S. pushing ahead with the Marshall Plan to rebuild war-torn Europe, returning it to a minimum threshold of economic advancement and political stability that would enable the continent to support the global narrative of a unipolar world as envisioned by Washington. Thereafter, a broad set of “norms and institutions that govern international relations as well as broad patterns of power distribution and economic flows across the world, most of it backstopped by American power and leadership” came into force, including the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (as well as the “Washington consensus” that they implied), and a variety of related organisations. All these institutions existed to put guardrails in place for international politics — in other words these organisations were used as leverage to limit the regional and global ambitions of any potential rival to the aforementioned unipolar balance of power.

The triumphs of Pax Americana

The argument made by some who see the continuation of the rules-based international order even through the turbulence of the Trump years is that throughout the history of Asia’s development, the U.S. has displayed the very same bullying tactics around the region that curbed and shaped the growth trajectory of Asian powerhouse economies. For example, Sandeep Bhardwaj argues that during the post-War years, when Japanese cloth imports of the U.S. outsold American domestic product, the U.S. in 1955 compelled Japan to agree to a voluntary export restriction that capped the latter’s share of the U.S. market. However, the U.S. has equally nurtured the quality of openness within the rules-based order, allowing room for Asian and Latin American economies to periodically assert themselves and play a larger role within limited spaces, thus introducing the necessary element of system flexibility that has helped it endure despite a series of economic and political shocks over the past half century.

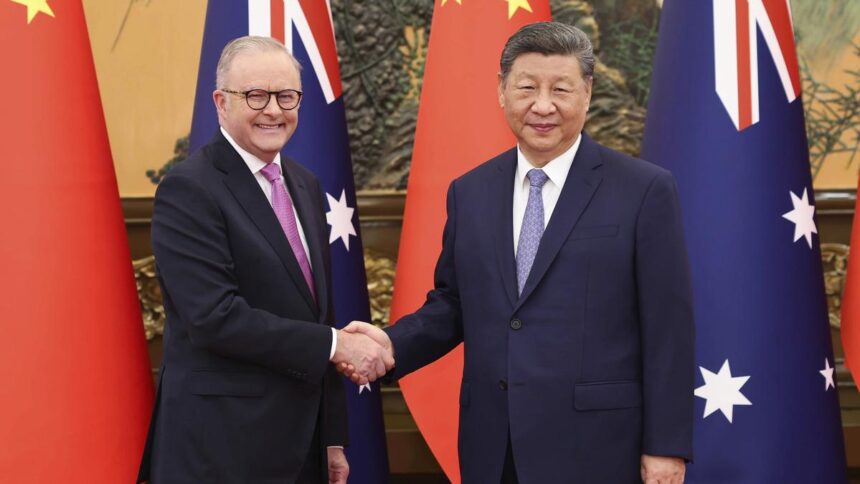

Examples cited of such openness within Pax Americana include the U.S. and developed nations encouraging developing countries to join the United Nations umbrella of institutions; getting China to join the WTO in 2001 after going slow on global concerns about Beijing’s human rights violations; supporting Japan’s entry to the G-7 in 1973; strongly backing the entry of China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Saudi Arabia into the G20; establishing the UN Millennium Development Goals to backstop the financing of industrialisation in emerging economies; and structural adjustment loans from the IMF. These loans, however, were a double edged sword, offering a financial lifeline for Asian countries while benefitting U.S. trade policy by forcing the opening up of these markets.

The extent of U.S.’ power

There is no denying that the rules-based international order is far from an authoritarian hierarchy of forced policy prescriptions and expected political genuflection of so-called subordinate Asian nations. Yet, it is fair to ask whether such a warped balance of power in favour of the U.S. could ever emerge, given the Asian trajectory of rapid economic growth built on global trading and capital systems, the collective social emancipation of people, the propagation of individual and institutional liberty, and the growing state capacity for meaningful regional action and collaboration. If the sense of agency and autonomous power of Asian nation-states is overlooked, then it leads to a false sense of U.S. munificence in “bestowing” openness and flexibility upon the rules-based order. In reality, the U.S., for all its economic heft and technological prowess had no choice but to find its own place within this complex matrix of competing nations worldwide, each strong in specific economic sectors, but perhaps less so in other areas.

Within this more reasoned paradigm of the global political economy, which neither denies the unipolarity of the present moment nor overstates the U.S.’s ability to impose its hegemonic ambitions on other nations in today’s multi-alliance, interconnected and interdependent framework of international engagement, it becomes clear that damage done to the rules-based liberal international order under the second Trump administration will transform the order to the point of it resembling a new order entirely.

Ironically, at the heart of this act of reshaping the rules-based liberal international order, are not so much the consequences of what the U.S. is inflicting upon Asian nations but rather its abrupt pulling of the rug from under the heels of Europe by undermining the ideological cause and financial prospects of NATO and leaving the continent exposed to the risk of ever-increasing depredations of Russia.

Similarly, the resoluteness with which Mr. Trump has tied his administration to the whims and fancies of the genocidal and warmongering causes of Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu will rewrite the playbook for everyone. This will impact the rulers of Saudi Arabia and Türkiye, rethinking regional political dynamics, as much as it will aspiring college students from India seeking admissions in countries other than the U.S. in the wake of compulsory social media scrutiny as a condition of visa issuance.

A new order

Yes, the silhouettes of the old rules-based liberal international order will continue to fall upon the new arrangements that the world will find itself forced to confront by the end of the second Trump term.

However, there can be no denying that it will indeed be a new order built on the rise of bilateral agreements in place of broader regional ones.

The newer order will feature the widespread use of economic sanctions to penalise political opponents across the globe in contravention of WTO norms; ever-growing skirmishes and limited wars; a reliance on drones and AI to settle territorial and other disputes; as well as a steady, catastrophic dismembering of global institutions fostering cooperation, reducing transactions costs and speaking up for human rights and standards of international engagement more broadly.

Pax Americana may well give rise to the next phase of its own evolution, Flux Americana.

Published – August 12, 2025 08:30 am IST