Back in 2019, to mark a decade of his brand Raw Mango, designer Sanjay Garg released a set of 10 objects that were billed as collectibles. They included items like the body armour of a Theyyam dancer made of acrylic, a terracotta bull inspired by an ancient Iranian artefact, and digestive powders stored in beautiful wood and brass boxes. It felt both puzzling and a power move because on the surface they appeared unrelated to the beautiful saris he’s known for, and yet there was a clamour from his audience base to possess it.

“Creative people are not uni-dimensional,” Garg tells me, on the phone from Chiang Mai in Thailand, where he’s browsing through a flea market. “I wanted to share with people the things I love — antiquities, culture, food — which in a way are a part of my brand. And I wanted them to be seen as such.” Since then, the number of craft and design-centric brands in India that have launched verticals dedicated to collectibles has exploded.

Sanjay Garg

| Photo Credit:

Amlanjyoti Bora

Theyyam body armour

These collectibles are often items that are extensions of the brand’s main product lines, but created with more labour and in single piece or limited numbers. Examples include embroidered panels that reproduce the works of renowned artists such as Neelima Sheikh, Ranbir Kaleka and Nikhil Chopra by Milaaya Art Gallery, the collectibles vertical of couture embroidery firm Milaaya Embroideries.

Ranbir Kaleka’s Baroque Blue

| Photo Credit:

Ryan Martis

Lamps and decorative objects made from hand blown glass that mirror the architecture of South India’s temples, by the creative minds behind Delhi’s Klove Studio. Decorative boxes and hair pins by the House of Sunita Shekhawat (the jewellery company specialises in meenakari enamelling). And Jaipur Rugs’ collectible carpets label, Aspura, which sells genuine antiques, and, as the brand’s artistic director Greg Foster puts it, “antiques of the future designed by prestigious names from contemporary culture”. The tone was set by their launch at India Art Fair 2025, which featured limited edition carpets conceived by artist Rashid Rana.

Jaipur Rugs’ The Court of Carpets campaign

| Photo Credit:

Neville Sukhia

“Adding objects that explain who you are, is a lovely way to expand your brand and your community. In a way, you’re deepening the linkage between your creations and your consumers.”Deepshikha KhannaDesigner

Shift in meaning and approach

All of this, some argue, flies in the face of the traditional definition of a collectible, which conventionally is described as an object that by virtue of its age, rarity and backstory is considered valuable by a collector. For example: an antique Chola bronze statue, the draft manuscript of Ponniyin Selvan with author Kalki’s notes, and in the design space, chairs designed by Swiss architect Pierre Jeanneret, in the 1950s, when he was building Chandigarh.

“It’s human nature to collect material things: shells, coins, textile. An object becomes a collectible [in the monetary sense] if someone is willing to set up a transaction around it and pay a value far higher than its core value,” says Ashvin Rajagopalan, founder of Chennai art and collectibles gallery Ashvita’s. “For that to happen, it takes time; the object has to become rare and have a backstory that moves the market. To take something that’s new and to say that it’s collectible, giftable, limited edition, rare, is to make it hold value. I think these are more marketing labels than a true collectible.”

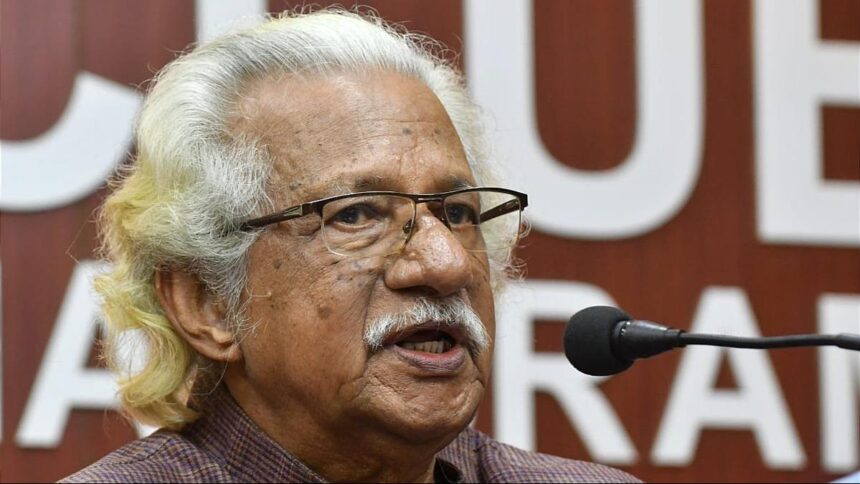

Ashvin Rajagopalan

Ranvir Shah, a noted collector of art and antiquities, counters this. “Brand extensions are what a creator thinks are commercially valuable items, which over a period of time may also appreciate,” he says. Shah runs Chennai-based Prakriti Foundation that regularly hosts events around art, culture and literature. “People like my father, for instance, collected Lladró products,” he adds, referring to the Spanish maker of fine porcelain home accessories and decorative objects. Today a legacy brand, its vintage productions are considered highly valuable by collectors. “Every time he travelled overseas, he would buy something he could afford, thinking it would appreciate in value. And they have. A Ganesha idol he bought for ₹5 lakh has gone up in value to over ₹8 lakh.”

Another example comes from Srila Chatterjee, co-founder of Mumbai-based design gallery 47-A and curator of Baro Market, a digital marketplace that regularly hosts offline sales of art and design-centric collectibles. “All the incredible work that [multi-disciplinary artist] Riten Mozumdar did for Fabindia [1966-2000] is a great example. People like my mother paid next to nothing for his textiles back then. Today, retrospectives of his work are hosted at top galleries, which makes his work collectibles. In my opinion, if someone is willing to pay a premium for an object that they want to keep in their homes, then it’s a collectible,” she says.

Ceramic collectible from Ashvita’s

“Creative people are not uni-dimensional. I wanted to share with people the things I love — antiquities, culture, food — which in a way are a part of my brand. And I wanted them to be seen as such.”Sanjay GargDesigner

Where craft takes centrestage

In the Indian context, many of the commercially available objects that are labelled as collectibles are touted to be rooted in one or more traditional craft. If the connection is authentic, that itself makes the object a collectible, opines Manju Sara Rajan, co-founder of Bengaluru design gallery KAASH.

Manju Sara Rajan

| Photo Credit:

Rohit Bijoy

The space works with internationally-trained designers and hereditary Indian craftspeople to create unique design-centric objects. Such as lights created by Italian designer Andrea Anastasio, collaborating with shadow puppetry artists from Andhra Pradesh, and furniture inspired by Chettinad’s kottan basketry weave, designed by Bengaluru-based architect David Joe Thomas. “By virtue of being handmade, such objects are few in number. They are usually the product of a special collaboration and you’re not going to be able to buy them elsewhere. So, you are buying into a craft legacy that may not exist in the future.”

There’s also an argument to be made, say industry insiders such as Deepshikha Khanna, ex-creative director of Good Earth, that extensions in the form of limited-edition collectibles are a clever way to expand a brand’s reach by appealing to a key reason of why an individual collects — to become a part of a community that appreciates the same things you do. “At the start, your customer is going to buy into your brand at a very superficial level by buying whatever your base product is,” says Khanna, who counts among her acquisitions Garg’s Theyyam body armour. “But how do you get them to go beyond that? Adding objects that explain who you are, is a lovely way to expand your brand and your community. In a way, you’re deepening the linkage between your creations and your consumers.”

Deepshikha Khanna

To do just that, lighting designers Gautam Sheth and Prateek Jain created a sub-brand, collektklove, that offers design enthusiasts smaller products that are offshoots of what they create for their main brand Klove Studio. Examples of Klove Studio’s work can be found in the bold, experimental chandeliers installed at venues such as Ran Baas The Palace hotel in Patiala. “We realised there’s an aspirational market of young professionals who appreciate good design,” says Jain, explaining why they decided to introduce smaller objects in a price range (from around ₹25,000) more affordable than their luxurious chandeliers. “These are objects, like table and floor lamps, which can be easily placed in homes, We’re also working on collaborations with designers whose aesthetic we like to create premium collectible products,” he adds.

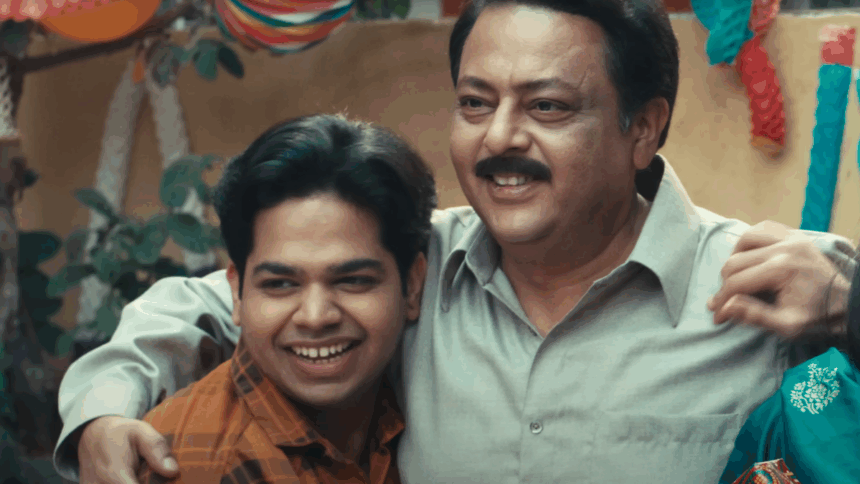

Prateek Jain (left) and Gautam Seth

collektklove’s Deepa candle stand

Depending on factors such as how many pieces of a collectible design object are being produced, the designers, the craft involved, and the storytelling behind it, prices can range from a few thousand rupees to six-figure tags. “Since we started in 2022, we’ve seen consistent growth of about 20% year-on-year,” reveals Tarini Jindal Handa, founder of Mumbai-based design gallery Aequo whose collaborative work with rural artisans in Karnataka and the Parisian designer Valériane Lazard, won the gallery a contemporary design prize at PAD Paris 2023. “Earlier, the U.S. was our dominant market. Now 40% of our buyers are Indian. Clearly, they’re drawn by the uniqueness and connection to their culture and heritage.”

Tarini Jindal Handa

Aequo x Chamar furniture

| Photo Credit:

Manan Sheth

“Earlier, the U.S. was our dominant market. Now 40% of our buyers are Indian. Clearly, they’re drawn by the uniqueness and connection to their culture and heritage.”Tarini Jindal HandaFounder, Aequo

Newer collectors lead the way

The rise in labels offering collectible design products, say experts, is in direct response to the consumer’s appetite for consumption. Which in turn is being fed by higher levels of affluence, increased awareness of global trends, and, to some extent, the recognition Indian craft practices have received from global design labels. Remember Dior x The Chanakya School of Craft — the hand embroidered mise-en-scène for the brand’s 2022 spring-summer show in Paris, for instance?

“When I first arrived in India 10 years ago, very few people were buying collectible design, and there was a handful of designers creating them. The scene has completely changed now,” says Foster. “Today you can see the appetite in collectors who are already buying from fairs like Design Miami, PAD London and Paris, and from design fairs such as Design Mumbai. Given that the contemporary art market is so developed, definitely the next commercial frontier is design.”

Greg Foster

A common refrain is that those who find art too daunting to invest in consider design more approachable. “Newer collectors especially no longer see art as equal to a painting. It’s also in the sofa that you might sit on or the jewellery you wear,” Chatterjee insists. Another factor that’s played a “significant role” in boosting consumption of design products: COVID-19. “I’ve seen studies that reveal how people, since they were spending more time at home, became interested in what their homes looked like,” reveals Chatterjee, which she says resulted in greater investments in art, interior design, and a big reason “why I feel a lot more things are being collected now than ever before”.

Aequo x Valériane Lazard

According to a recent report by the U.S.-based research firm Grand View Research, India’s design-centric collectibles market is predicted to hit revenues of around $22 billion by 2030. A valuation that not only includes art, design and antiquities but also objects with lived histories — such as furniture, stamps, currency, figurines, vinyl records, action figures, books, vintage tech and printed imagery. Which could well mean more collectible design being produced.

As I prepare to hang up, Garg tells me he’s back to designing a new series of objet d’art. When he mentions a toothpick, I wonder if he’s only teasing.

The writer is based in Mumbai and reports on travel and culture.