In June 2014, days after Prime Minister Narendra Modi had been sworn in for the first time, one of the first high-level visitors from outside the SAARC region was Wang Yi. Mr. Wang, who was appointed the Foreign Minister of China in 2013, travelled to New Delhi as Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping to meet Mr. Modi, whom he called an “old friend of China”, referring to Mr. Modi’s visits during his tenure as Gujarat Chief Minister, and said the NDA’s return to power had “injected a new vitality into an ancient civilisation”.

Mr. Wang’s mission was clear — to secure a visit by Mr. Xi to Delhi that September, and to invite Mr. Modi to Beijing soon after. Both visits were cleared quickly. A few days after Mr. Wang’s visit on June 8-9, the government also decided to put off two other engagements: the India-U.S.-Japan trilateral (the Quad was not revived until 2017), set for June 23-24 in Delhi, was cancelled, and Mr. Modi postponed his visit to Japan that had been fixed for July 3-5, ostensibly due to an upcoming Parliament session, much to his hosts’ disappointment. Speculation in South Block was rife: did the Chinese Foreign Minister have something to do with the decisions, to clear the “optics” before the Xi visit in September 2014?

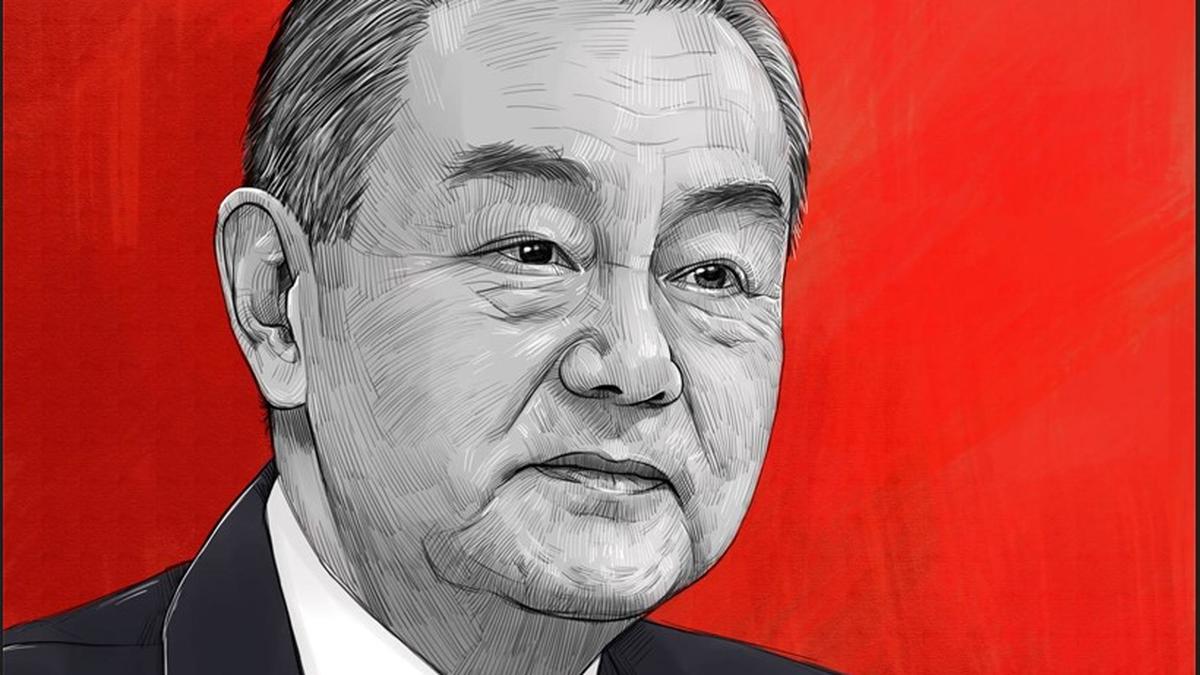

Called the ‘silver fox’ for his grey haired visage as much as for his slick manner, Wang Yi is now the unassailable Czar of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, with more sway than other Ministers due to his seniority in the party structure.

Insiders point out that he wears several hats now — he was elevated to the elite 24-member Politburo in 2022, and is Director of the Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs. He was elevated to the Politburo after the informal retirement age of 68, another sign of his clout, and although he handed over charge as Foreign Minister to Qin Gang in December 2022, he was brought back within months.

The gist

After finishing his schooling in 1969, Wang Yi was “sent down” as part of the ‘Xiaxiang’ movement during the Cultural Revolution to work in the icy climes of Heilongjiang province

He studied Japanese history and language during college thereafter in Beijing, and joined the Foreign Ministry in 1982

He was appointed the Foreign Minister of China in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, and elevated to the elite 24-member Politburo in 2022

Like Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and more recently External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, Mr. Wang is part of a breed of seasoned and professional Foreign Ministers who present and sell their leader’s political vision in diplomatic terms. In the 2010s, he was credited with China’s ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy, of abrasive and assertive public messaging that reflected China’s hard power status. However, when Chinese popularity dipped worldwide, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, Mr. Wang was also credited with abandoning the policy, mending fences, and replacing ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats in embassies worldwide with more polished colleagues.

Mr. Wang’s education in state-fare began, as many in his generation’s did, when he was “sent down” as part of the ‘Xiaxiang’ movement during the Cultural Revolution to work in the icy climes of Heilongjiang province, where he was recruited by the ‘Northeast Construction Army Corps’, after finishing his schooling in 1969. He studied Japanese history and language during college thereafter in Beijing, and joined the Foreign Ministry in 1982. He served twice in the Chinese Embassy in Japan, including as Ambassador from 2004 to 2007.

Backroom talks

South Block Mandarins had an introduction to Mr. Wang’s manner, more suave but also more purposeful than his predecessors, in the early 2000s. As Vice Foreign Minister for Asian Affairs, he had conducted many of the backroom negotiations to prepare for Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee’s visit to Beijing in 2003. Officials at the time remember his hard bargaining for a deal on India’s recognition of China’s control over Tibet and for China to recognise Sikkim as an Indian State. Eventually, Indian officials felt disappointed that although the joint declaration issued had an explicit paragraph saying India “recognises that the Tibet Autonomous Region is part of the territory of the People’s Republic of China and reiterates that it does not allow Tibetans to engage in anti-China political activities in India”, the paragraph on Sikkim was not a similarly unequivocal declaration, with only a designation of ‘Sikkim State’ referring to the opening of border trade at Nathu-La pass.

“He is suave and sophisticated, but also quite tenacious, and can dig his heels in during negotiations, so it is necessary to always be vigilant,” says former Ambassador to China Ashok Kantha, who was posted to Beijing in 2014-2016, and had served on the China desk in the 2000s. “Indian officials have often had to push back in talks, but found him a result-oriented interlocutor,” he added.

As a former Director of China’s ‘Taiwan affairs office’ (2008-2013), Mr. Wang has been keen for India to refer to its ‘One China’ policy recognising Beijing’s control over all of China, including Taiwan. However, New Delhi decided to stop including the phrase in its statements since 2010, in protest against Chinese policy of issuing stapled visas to Indians from Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir. When pressed by Mr. Wang to reaffirm India’s adherence to the ‘One China’ policy, former External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj, who had been briefed about Mr. Wang’s persuasive skills, once retorted: “If China affirms its One India policy, we will consider it”. Nonetheless, Mr. Wang has persisted, including this week in talks with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, where the Chinese side slipped a line on Taiwan into its readout. The Ministry of External Affairs had to scramble to clarify its position.

Diplomatic missions

As Foreign Minister, Mr. Wang is known for many diplomatic missions over the past decade, including bringing U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to Beijing to kickstart talks for Mr. Xi’s Mar-a-Lago summit with U.S. President Donald Trump in April 2017 and brokering talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia to reopen diplomatic ties in 2023. He also helped with U.S.-North Korea talks; more recently between Cambodia and Thailand, Afghanistan and Pakistan, between Myanmar’s military junta and armed ethnic groups as well as a bid in 2023 to bring Russia and Ukraine to the table for talks.

India has often been concerned about his ‘South Asian’ groupings, including a recent one with Pakistan and Bangladesh on trade, which appear to be part of a plan to create a ‘SAARC minus India’. As Foreign Minister, but also Special Representative for border talks, Mr. Wang now deals in Delhi with both Mr. Jaishankar and National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, and is known for his tough but smooth-talking engagement style during the four-year military standoff after PLA transgressions along the Line of Actual Control and the Galwan clashes, and earlier, during the Doklam standoff.

Setting up the first “inter- governmental organisation for international mediation” in Hong Kong in May this year, Mr. Wang outlined his vision. “The birth of the mediation centre will help transcend the ‘you-lose-I-win’ zero-sum mentality, promote the amicable resolution of international disputes and foster more harmonious international relations,” he said. However, for interlocutors bruised during hard-fought diplomatic negotiations with him, Mr. Wang’s version of “win-win” is more aligned to the old maxim — when Beijing says “win-win”, it means China must “win twice”.

Published – August 24, 2025 01:07 am IST