In 2017, the annual economic costs of all tobacco products for the population aged 35 years and above in India were estimated at ₹1,773.4 billion (1.04% of GDP), in addition to ₹566.7 billion (0.33% of GDP) in annual healthcare costs attributable to second-hand smoking. (These costs include “direct medical and nonmedical expenditures, indirect morbidity costs, indirect mortality costs of premature deaths.”)

To control the burden of tobacco-related diseases, there is an urgent need to review and strengthen existing tobacco control measures taken by the Indian government.

Gaps in the law

The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA), 2003, is a stringent Act; however, its implementation has varied and is poor in several Indian States. The legislation also has various other shortcomings that require urgent attention.

First, it lacks focus on smokeless tobacco (SLT); although laws like the Food Safety and Standards (Prohibition and Restriction on Sales) Regulations, 2011, contribute to its control, they are relatively weak and poorly enforced. Being cheaper, culturally acceptable and associated with lesser stigma, SLT is the more commonly consumed form of tobacco in India. The addictive potential of SLT may be variable, but it is also known to be more carcinogenic than smoked forms of tobacco.

Second, the COTPA also fails to tackle the growing influence of surrogate advertisements, especially for SLT, in promoting tobacco use. Exposure to tobacco advertisements is known to promote initiation in non-consumers. Though direct tobacco advertisements are banned in India, companies use similar packaging for mouth fresheners to build brand recognition and promote tobacco through classical conditioning.

While warning signs are mandatory, movies, social media, and over-the-top (OTT) streaming platforms are other ways of indirectly promoting tobacco use. Exposure to tobacco use in movies is known to be associated with the initiation of smoking in teens and young adults. Hence, strict bans need to be implemented on both surrogate advertisements and indirect promotion in the media.

Third, there are no direct provisions in COTPA for fiscal measures to curb tobacco use. Raising excise taxes is the most effective way to reduce consumption, yet India’s tobacco taxation remains inadequate and uneven. The tax burden on bidis, the most consumed smoked product, is just 22%, and about 50% on cigarettes—far below the World Health Organisation’s recommended 75%.

SLT is also poorly taxed as it’s largely produced in the unorganised sectors. Since the GST rollout in 2017, only two minor tax hikes (in 2020–21 and 2022–23) have been made, each raising overall tobacco taxes by just 2%. Combined with rising incomes, this has made tobacco more affordable. By avoiding substantial tobacco tax hikes, the Indian government is missing a key revenue opportunity and worsening public health outcomes.

Fourth, COTPA rules should mandate regular evaluation of tobacco warning labels. Although updated every two years, there’s limited evidence on their effectiveness in preventing tobacco use.

Unlike many European countries that use packaging to educate users about a range of tobacco-related harms – such as cancer, fatal lung disease, peripheral vascular disease, harm during pregnancy, and infertility – India’s warnings rely mainly on fear-based messaging. From 2016 to 2020, warnings focused only on oral cancer and later on generic messages about early death.

Given that packaging is a highly cost-effective public health tool, it should be better leveraged to inform and empower users to quit. India mandates 85% health warnings on tobacco packs, but should also adopt plain packaging to further reduce the appeal and use of tobacco.

India is one of the few countries to ban e-cigarettes. However, poor implementation of the Prohibition of Electronic Cigarettes Act (PECA) 2019 has also resulted in an increasing threat of e-cigarettes to public health in India. Despite the ban, e-cigarettes can be purchased online in India, making them more accessible to adolescents. There is an urgent need for the stringent implementation of this Act to protect the public from this health hazard.

Need for holistic approach

The National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP), which currently focuses mainly on awareness generation and COTPA implementation, needs to take a holistic approach to tobacco control by addressing the social and commercial determinants of tobacco use. Poverty, stress, unemployment, and hunger are known to impact tobacco use and cessation rates. The existing biomedical approach of tobacco control through tobacco cessation clinics fails to address the underlying social determinants of tobacco use, while also being inadequate in providing access to tobacco cessation services to cater to the large number of tobacco users requiring support.

The Tobacco Free Education Institute (ToFEI) currently promotes awareness in schools through posters and biannual activities, but lacks the scientific rigour needed for effective tobacco control. In contrast, the U.S.’s national public health agency, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends comprehensive school-based strategies in the U.S., including enforcing tobacco-free policies, integrating prevention education from kindergarten to grade 12, training teachers, involving families, supporting cessation for students and staff, and regularly evaluating programmes.

ToFEI falls short in several areas: it offers no cessation support for children, lacks teacher training and parental involvement, does not actively educate students on tobacco harms, and has no evaluation mechanism.

Better regulation, control

It is also crucial to realise that the tobacco industry is always one step ahead of public health researchers, as it has access to its real-time sales data to adapt sales strategies while public health researchers are unaware of the most recent trends in tobacco consumption.

Realising the ‘Tobacco Endgame’ in India requires a comprehensive, multipronged strategy. Key ministries—including Education, Law and Justice, Social Justice and Empowerment, Commerce and Industry, Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Finance, Information and Broadcasting, and Health and Family Welfare—must coordinate efforts to address both demand- and supply-side drivers of tobacco use.

Greater investment is needed not only in developing and implementing control measures but also in strengthening research institutions to produce regularly updated, robust data. This data should inform assessments of tobacco use, evaluate control strategies, guide cessation interventions, and identify regional policy gaps.

Establishing an independent oversight body is also essential to monitor and expose industry interference. Ultimately, sustained collaboration among policymakers, implementers, and researchers is crucial to achieving a tobacco-free India.

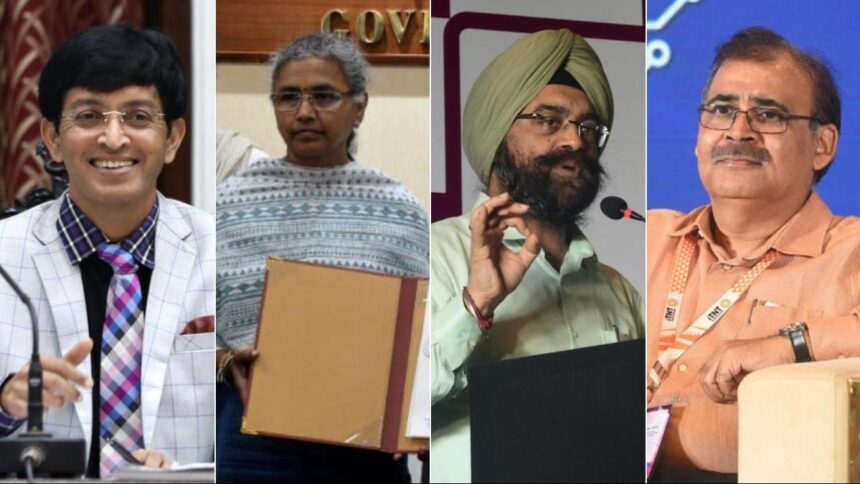

Dr Parth Sharma (MD student), Dr Amod L. Borle (associate professor) and Dr M.M. Singh (Director Professor and Head) work at the Department of Community Medicine, MAMC, Delhi. Dr Pragati Hebbar is the Assistant Director Research at IPH Bengaluru. Dr Rijo M. John is a health economist.