Maratha community members celebrate after the Maharashtra government accepted most of activist Manoj Jarange Patil’s demands, including granting eligible Marathas Kunbi caste certificates which will make them eligible for reservation benefits available to OBCs, in Mumbai, on September 2.

| Photo Credit: PTI

The story so far:

The leader of the opposition in Bihar, Tejashwi Yadav, has declared that if voted to power, their alliance would increase reservation to 85%. In another development, the Supreme Court has issued notice to the Union government on a petition demanding the introduction of a ‘system’ similar to the ‘creamy layer’ for reservations among the Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST)

What are constitutional provisions?

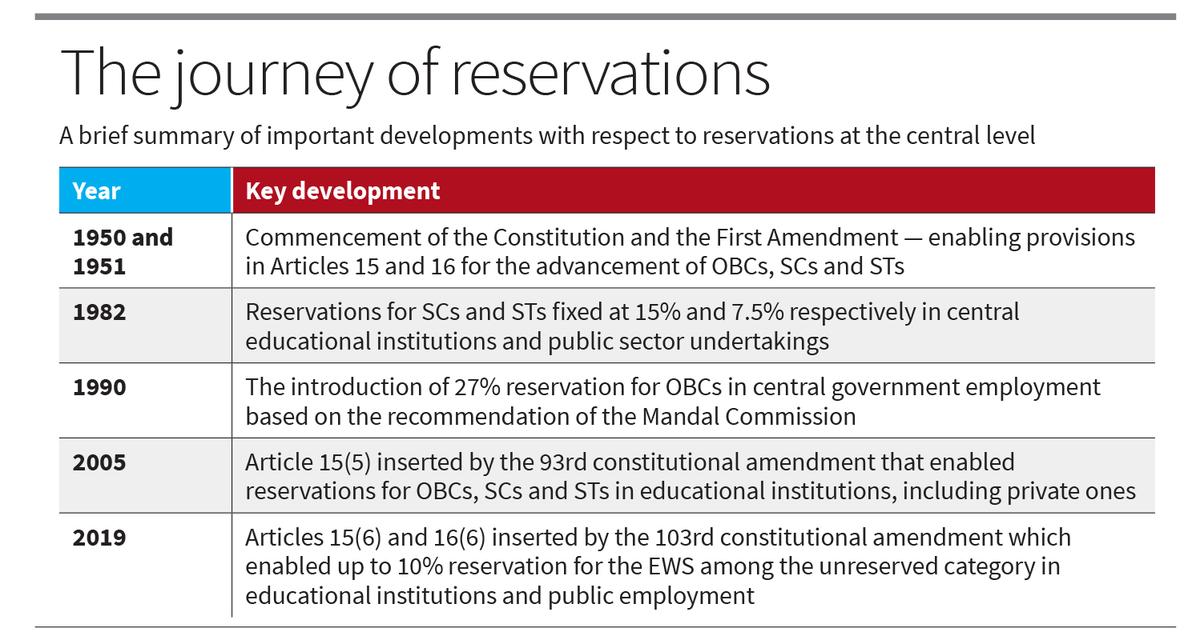

Articles 15 and 16 guarantee equality to all citizens in any action by the state (including admissions to educational institutions) and public employment respectively. In order to achieve social justice, these Articles also enable the state to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes or Other Backward Classes (OBCs), SCs and STs. A brief summary of important developments with respect to reservations at the central level is provided in the Table. The reservation in the Centre at present stands as follows — OBCs (27%), SCs (15%), STs (7.5%) and for the Economically Weaker Section (EWS), 10%, resulting in a total reservation of 59.5%. The reservation percentages vary from State to State according to their demographic profile and policies.

What have courts ruled?

The issue arises due to two ostensibly competing aspects of equality — formal and substantive. The Supreme Court in Balaji versus State of Mysore (1962) noted that reservations under Articles 15 and 16 for backward classes should be ‘within reasonable limits’ and should be adjusted with the interests of the community as a whole. The court further ruled that such special provisions for reservation should not exceed 50%. This is seen as an endorsement of formal equality where reservations are seen as an exception to equality of opportunity and hence cannot exceed 50%.

Substantive equality on the other hand is based on the belief that formal equality is not sufficient to redress the difference between groups that have enjoyed privileges in the past and groups that have been historically underprivileged and underrepresented. A seven-judge Bench in State of Kerala versus N. M. Thomas (1975) have broached the aspect of substantive equality. The court in this case opined that reservation for backward classes is not an exception to equality of opportunity but is an assertion and continuation of the same. However, since the 50% ceiling was not a question before the court, it did not give a binding judgment on this aspect in the case.

In the Indra Sawhney case (1992), a nine-judge Bench upheld the 27% reservation for OBCs. It opined that caste is a determinant of class in the Indian context. Further, in order to uphold the equality of opportunity, it reaffirmed the cap of 50% for reservation as held in the Balaji case, unless there are exceptional circumstances. The court also provided for the exclusion of a creamy layer within OBCs. In the Janhit Abhiyan case (2022), the court by a majority of 3:2 upheld the constitutional validity of the EWS reservation. It held that economic criteria could be a basis for reservation and opined that the 50% limit set in the Indra Sawhney case was meant for backward classes while the EWS reservation of 10% is for a different category among unreserved communities.

What are the competing arguments?

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar in his Constituent Assembly speech in November 1948 justified the need to have reservations for backward communities that have been left out in the past. He also opined that reservations should be confined to a minority in order to uphold the guaranteed right of ‘equality of opportunity.’

However, there has been a growing demand for increasing the reservation percentage beyond the judicial cap of 50% to reflect the proportion of backward classes in the population. The demand for a caste census has been strong in order to have actual data about this proportion rather than mere estimates. It must also be noted that as per various government replies in Parliament, 40-50% of seats reserved for OBCs, SCs and STs in the Central government remain unfilled.

Another contentious issue relates to the concentration of reservation benefits. The Rohini Commission, set up for providing recommendations on the sub-categorisation among OBC castes, has estimated that 97% of reserved jobs and seats in educational institutions have been garnered by just around 25% of the OBC castes/sub-castes at the central level. Close to 1,000 of around 2,600 communities under the OBC category have had zero representation in jobs and educational institutes.

A similar issue of concentration of reservation benefits persist in SC and ST categories as well. There is no exclusion of ‘creamy layer’ for these communities. In State of Punjab versus Davinder Singh (2024), four judges of a seven-judge Bench impressed upon the Central government the need to frame suitable policies for the exclusion of ‘creamy layer’ in SC and ST reservations. However, the Central government in a cabinet meeting in August 2024 reaffirmed that the ‘creamy layer’ does not apply to reservations for SCs and STs.

Critiques who are against the extension of a ‘creamy layer’ to SCs and STs argue that the vacancies for these communities are anyway not fully filled. Therefore, the question of a ‘creamy layer’ within such communities usurping the opportunities of even more marginalised castes does not arise. It is also likely that the exclusion of a ‘creamy layer’ based on any criteria will result in an even more increased backlog of vacancies. There is also a fear that such backlog vacancies may be converted in the long run to unreserved seats thereby depriving the SCs and STs of their rightful share of opportunities.

What can be the way forward?

Right to equality of opportunity is a fundamental right and an increase in reservation up to 85% may be seen as violating such right. Nevertheless, substantive equality through affirmative action is required to uplift the underprivileged. Based on empirical data of the ensuing Census in 2027, which will also enumerate backward castes, there must be wide ranging discussions with all stakeholders to arrive at a suitable level of reservation. Equally important is to implement sub-categorisation among the OBCs as per the Rohini Commission report based on Census data. With respect to SCs and STs, as demanded in the plea before the Supreme Court, a ‘two-tier’ reservation system may be considered. Under such a scheme, priority would be given to more marginalised sections before extending it to those who are relatively well-off within those communities. These measures would ensure that benefits of reservation reach the more marginalised among the underprivileged in successive generations.

It must also be borne in mind that considering the opportunities available in the public sector and the young population of our country, any scheme of reservation would not meet the aspirations of large sections of the society. There must be sincere efforts to provide suitable skill development mechanisms that would enable our youth to be gainfully employed.

Rangarajan. R is a former IAS officer and author of ‘Courseware on Polity Simplified’. He currently trains at Officers IAS Academy. Views expressed are personal.

Published – September 04, 2025 08:30 am IST