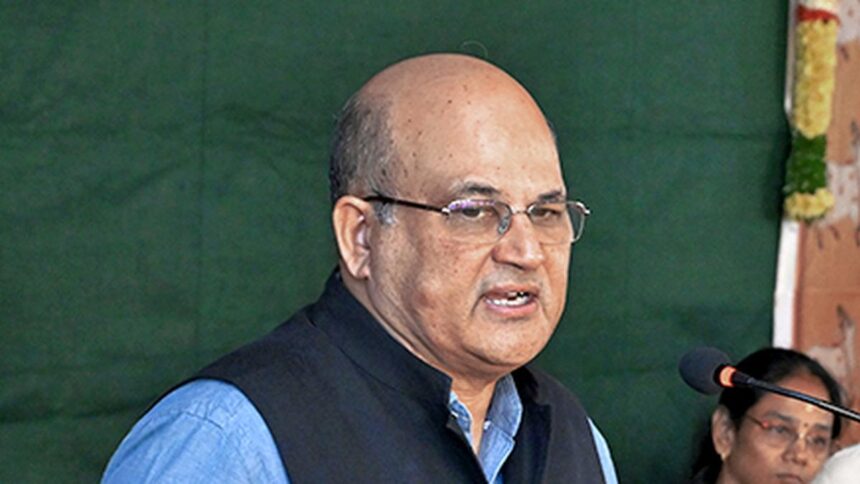

Prof. Rajib Shaw

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

In the wake of the devastating landslides that ravaged Wayanad last year, disaster management expert Prof. Rajib Shaw of Keio University, Japan, has called for a fundamental shift in India’s disaster preparedness strategy — urging that early warning systems be embedded directly within communities, and schools be transformed into localised early warning nodes.

Prof. Shaw led a team of experts from the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, the Indian Institute of Management-Kozhikode, the National Institute of Technology-Calicut, and Keio University, Japan, in a study based on extensive on-the-ground investigations into the Wayanad landslides. The comprehensive report, titled ‘Wayanad Landslides 2024: Early Warning System — Changing the Last Mile to the First Mile,’ was released in Kozhikode on Wednesday (August 6, 2025).

The study proposes that teachers serve as disaster awareness ambassadors, while students act as information disseminators within their families and communities. “The people in Wayanad received warnings but did not act on them. That gap between warning and response is what drove us to investigate this more deeply,” Prof. Rajib Shaw said in an interaction with The Hindu on Friday.

He pointed out that the lapse resulted from a combination of behavioural, cultural and institutional factors that collectively hindered timely evacuation and preparedness.

According to the report, the landslide that struck on July 30, 2024—one of the deadliest in Kerala’s history—claimed nearly 400 lives, injured over 200 people, and displaced around 7,000. More than 1,500 homes were destroyed, with economic losses estimated at over ₹281 crore.

The report identifies a lethal mix of factors behind the tragedy, including extreme rainfall of 409 mm in 24 hours and human-induced vulnerabilities such as unchecked deforestation, land-use changes, poor construction on fragile terrain, and increasing population and tourism pressures on the ecologically sensitive Western Ghats. It also directly links climate change to the intensified monsoon that triggered the disaster.

The failure in disaster response was not due to a lack of warnings but a breakdown in communication and institutional coordination, leaving communities as the ‘last mile’ in a flawed system instead of the empowered ‘first mile’ of resilience. Local panchayats lacked disaster literacy and training, while official communications were stalled in bureaucratic delays, the report said.

Prof. Shaw, former Kyoto University faculty and Chair of the United Nations Global Science Technology Advisory Group, said that in Japan, schools serve as default evacuation centres and hold annual drills tailored to regional risks—be it a tsunami, earthquake, or landslide. “Teachers, students, and families know their roles during a disaster. That is the kind of cultural shift we need here,” he added.

Dispelling the notion that technology was at fault in Wayanad, Prof. Shaw pointed out that the real breakdown lay in how the public responded. “Without awareness, drills, disaster training, or a culture of preparedness, alerts became just noise. People did not know what to do,” he said, adding that bridging the gap between institutions and communities must now be Kerala’s top priority.

Prof. Shaw emphasised that every effective early warning system rests on three crucial pillars — timely and accurate information, community behaviour and perception, and clear evacuation mechanisms. “In Wayanad, the technology worked, and warnings were issued. But the second and third pillars collapsed,” he said.

Published – August 07, 2025 08:29 pm IST