The ongoing special intensive revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar has led to a discussion that goes beyond a mere update to the voter list. As part of this initiative, discussions have been held on requiring certain proof of identity and citizenship — most notably, the birth certificate — for voter list verification. As the Election Commission continues to insist that its demand for documents is reasonable, and that most voters do have at least one of these documents, the issue has assumed critical importance, especially in light of the proposal to expand the SIR exercise to other States. Opponents of the SIR have been arguing that such an exercise will only lead to the exclusion of a large number of voters. In a democracy, the broadest possible inclusion of all eligible persons on the electoral rolls is the most basic requirement of a free and fair election system.

Therefore, finding out which documents voters actually possess, who are the ones less likely to possess such documents, and what might be the proportion of citizens likely to face exclusion from electoral rolls, are critical matters in assessing the feasibility and inclusivity of measures such as the SIR. In a country as socio-economically and geographically diverse as India, documentation access varies widely due to differences in administrative infrastructure, historical record-keeping, literacy levels, and public awareness. Above all, the State-level capacity and practice of record-keeping and the process of making documents easily available to citizens are variables that may result in exclusion in some States more than in others.

Lokniti-CSDS conducted a study across the States of Assam, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal and the National Capital Territory of Delhi to understand the types of documents people possess and their views on making the birth certificate and similar other documents compulsory for voter verification.

The larger picture

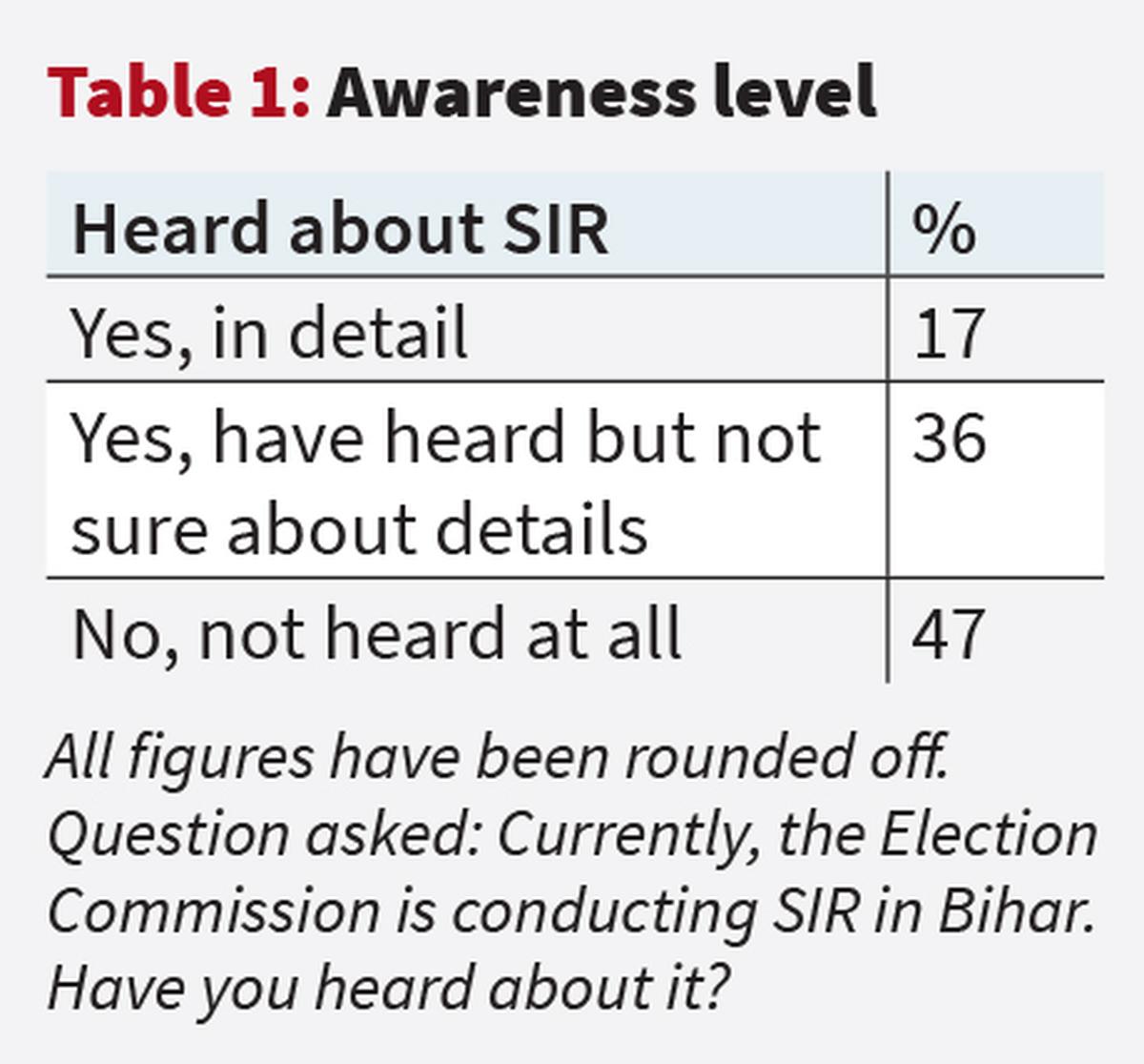

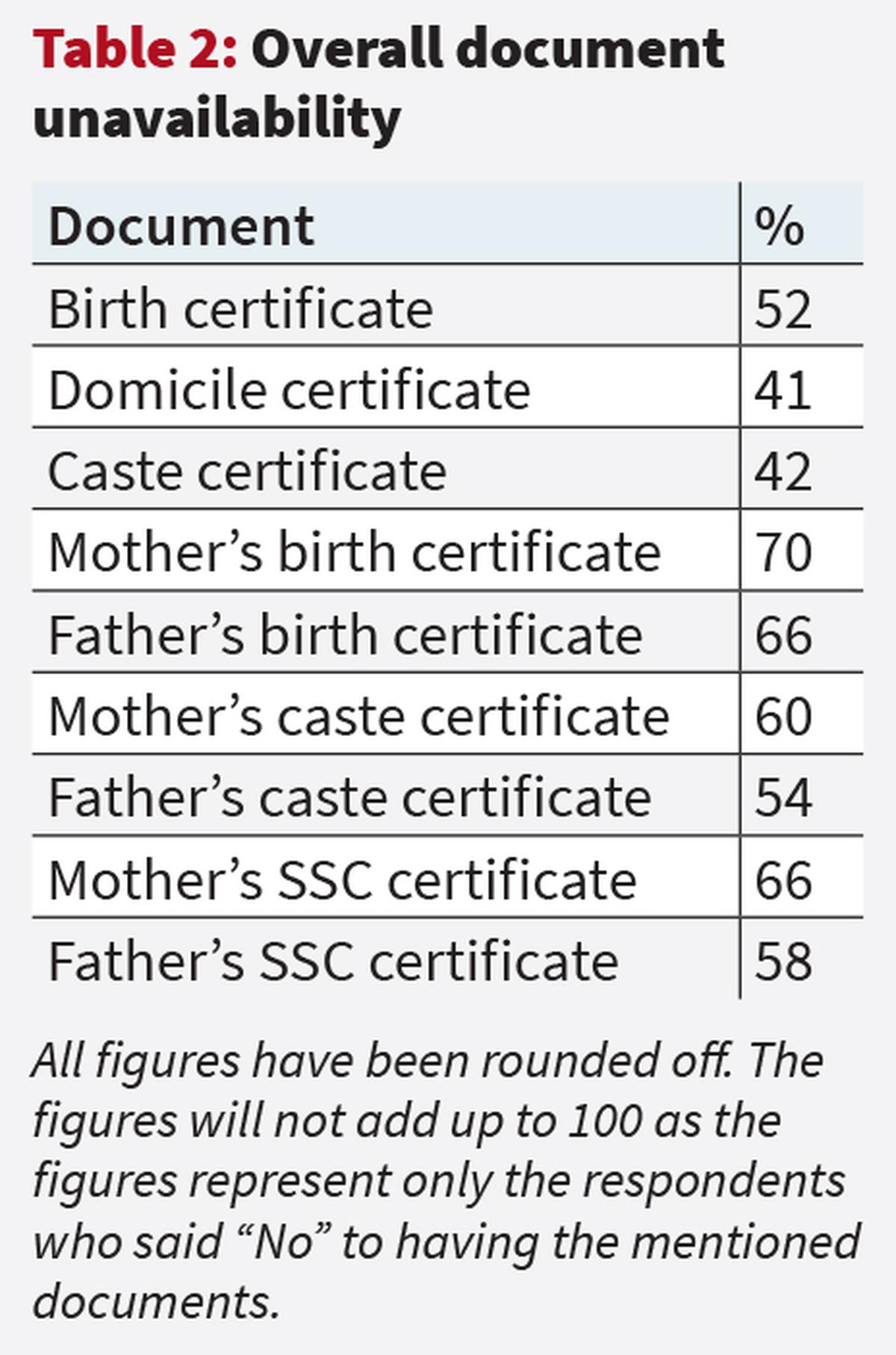

In spite of the ongoing debate in the media, only a little over one-third (36%) of respondents from our entire sample were aware of the SIR exercise or the documents that are required. More than half of the respondents said that they do not have a birth certificate. At least two in five did not have a domicile certificate or a caste certificate. As required by the SIR, those born after 1987 have an additional responsibility of having citizenship proof of at least one of their parents (and for both parents if born after 2003). Data from the survey show that this is a far more difficult condition to fulfil for the vast majority of the respondents. While at least two-thirds said they did not have their parents’ birth certificates, a similar proportion said they had neither an Secondary School Certificate (SSC) certificate nor a caste certificate.

How does this lack of necessary documents pan out across the States?

Clearly, it will exclude some citizens and more importantly, citizens from weaker sections in particular will have to keep running from pillar to post to obtain the documents or face exclusion.

India’s no-document citizens

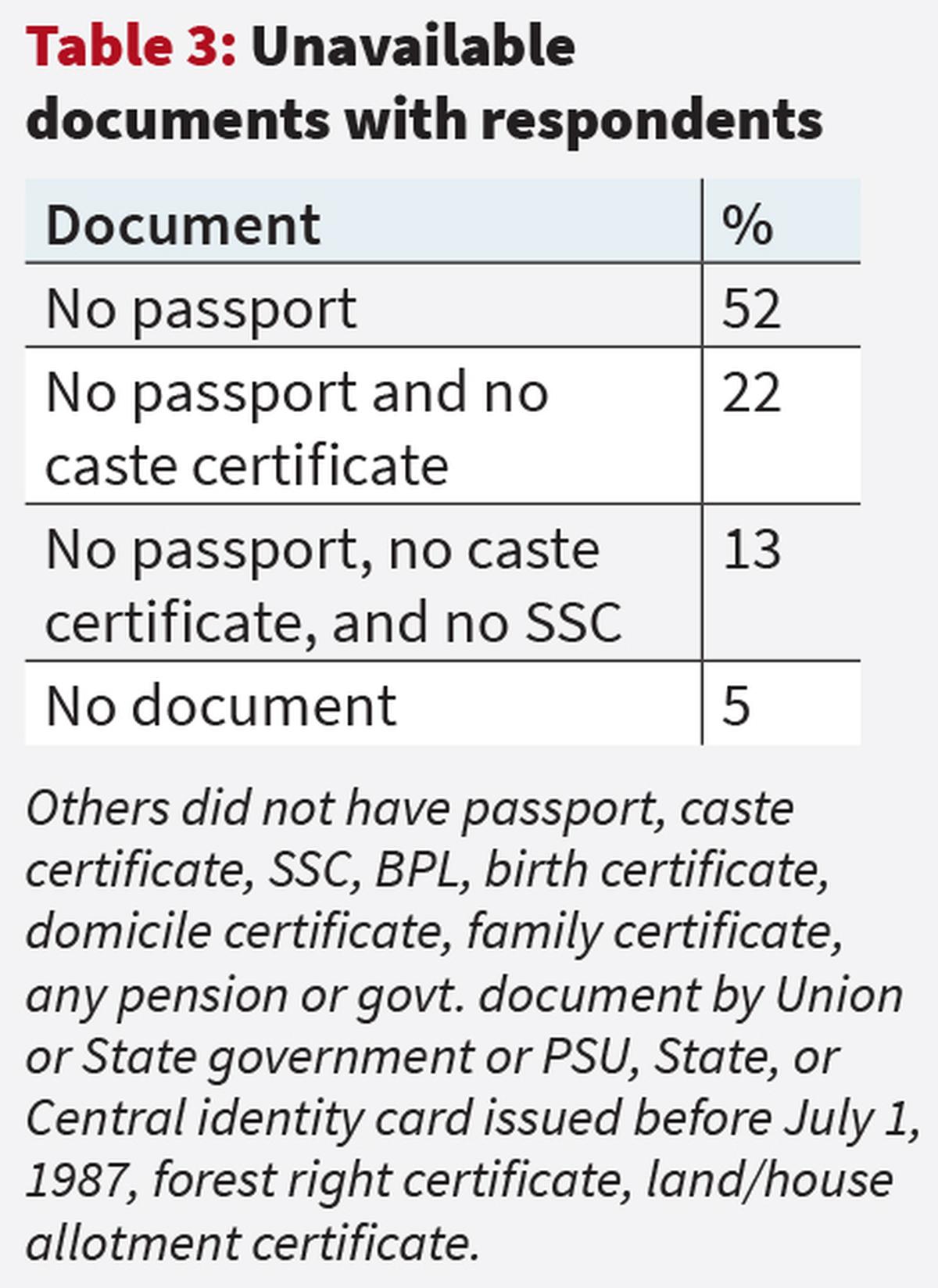

Roughly 5% of respondents did not have any of the 11 documents mandated by the EC. While there are slightly more women than men in this category of “No Document Citizens”, three-fourths of them are from the lower half of the economic order, while more than one-fourth are SC, and over 40% are OBC.

EC’s demand for birth certificate

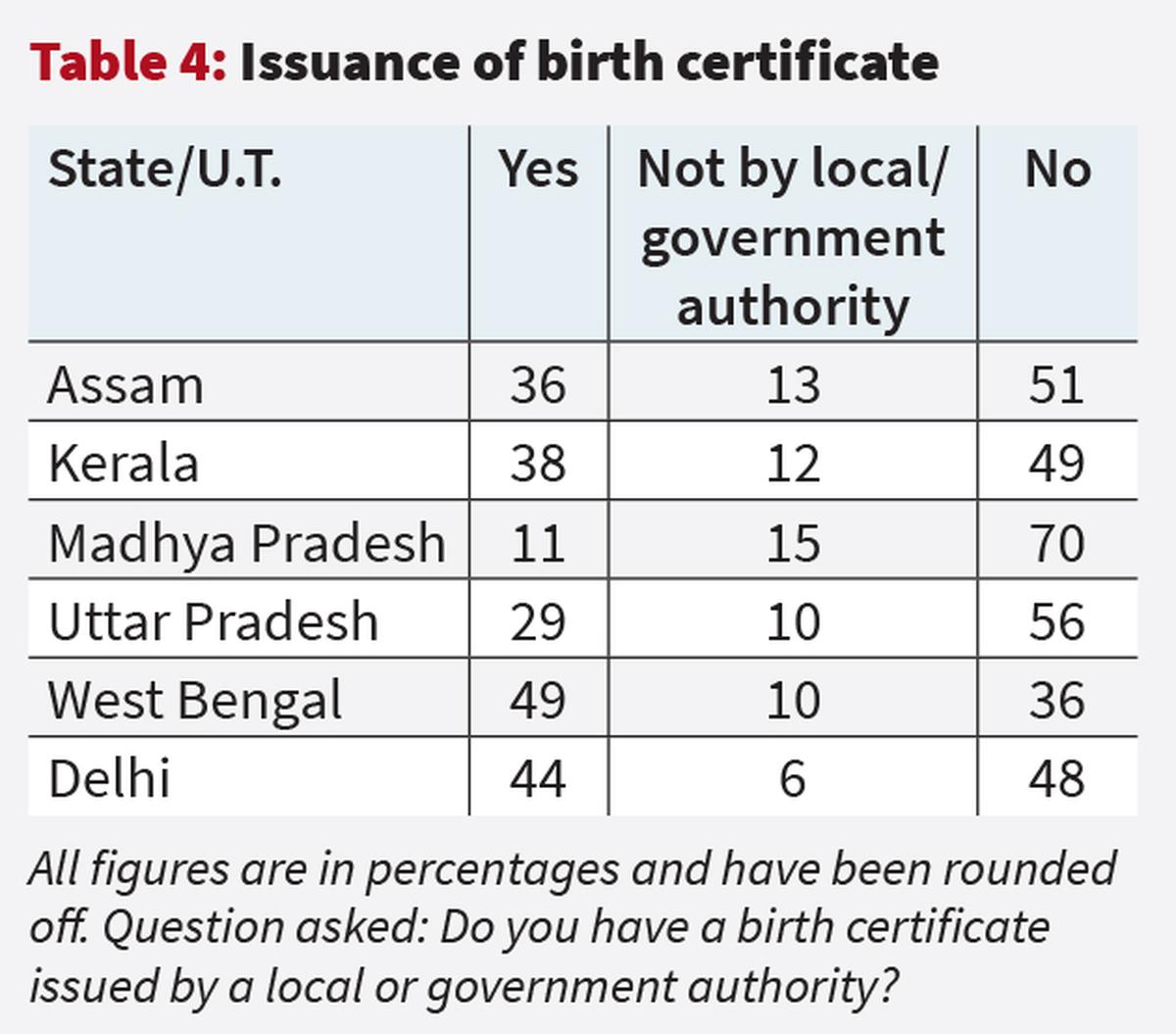

The proportion of respondents having a birth certificate issued by a local or government authority varies widely, as highlighted in Table 4. At the lower end, Madhya Pradesh records only 11%, indicating large documentation gaps. Assam (36%) and Kerala (38%) fall in the mid-range, while Delhi (44%) and West Bengal (49%) areslightly better. Even in these States, at the higher end, at least half of the respondents do not have the document.

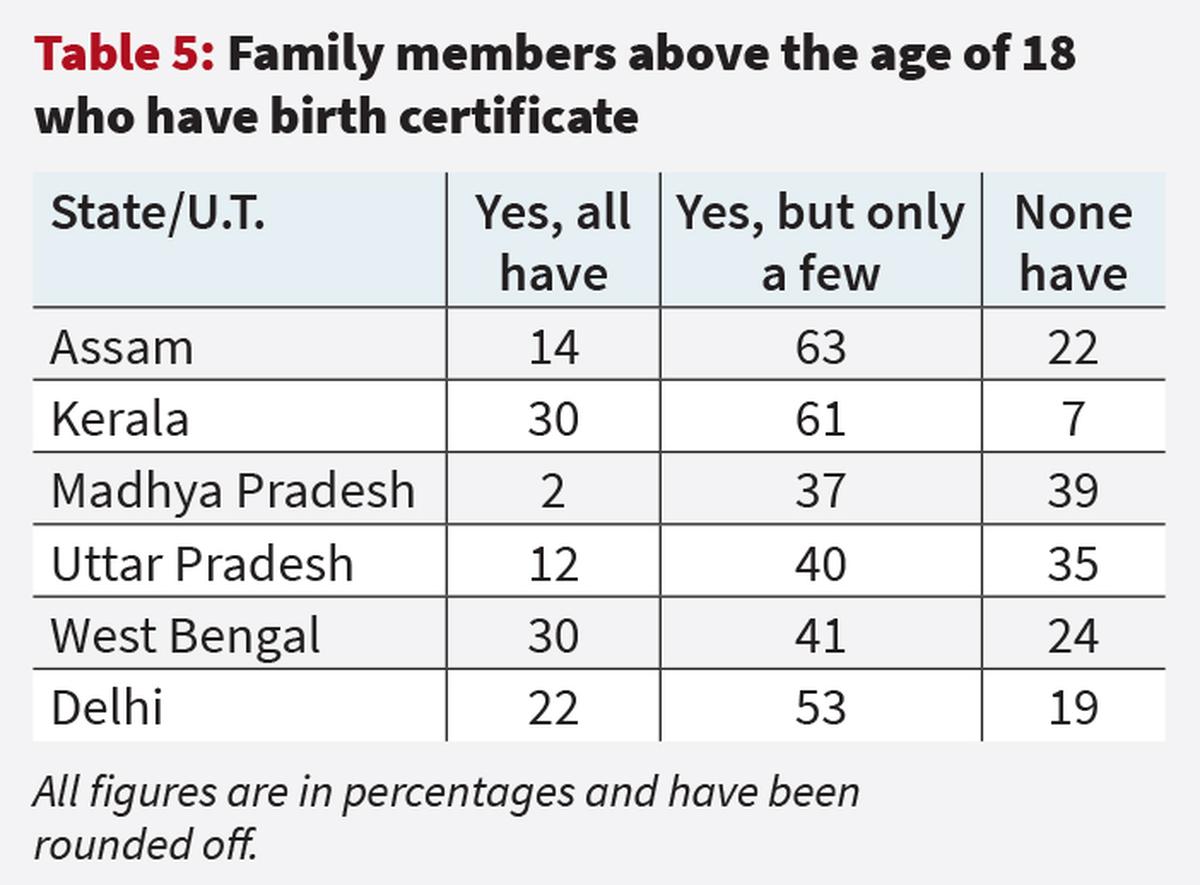

Within households, as shown in Table 5, the coverage of birth certificates among members aged above 18 remains low. Only Kerala and West Bengal report that three in 10 households have all adult members with a certificate, while in Madhya Pradesh, just 2% reported the same, and close to four in 10 say none of the adults have it. Assam and Uttar Pradesh also show low full-coverage rates — 14% and 12%, respectively.

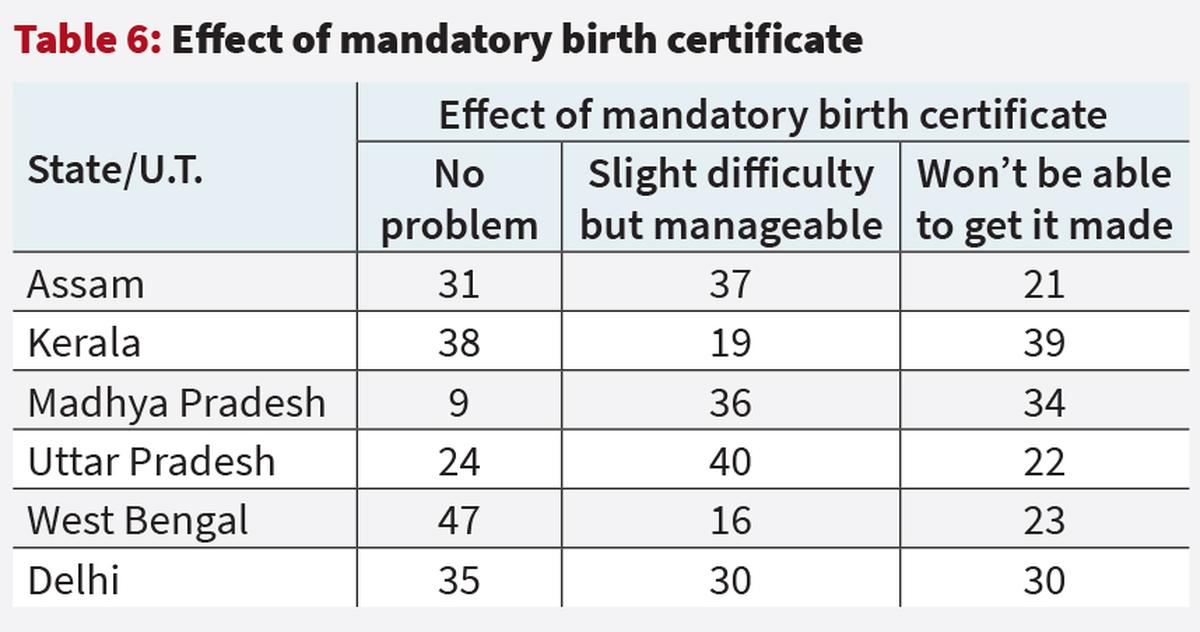

Is it really easy to obtain a birth certificate? If the requirements were made mandatory, exclusion risks would be high in some States, as highlighted in Table 6.

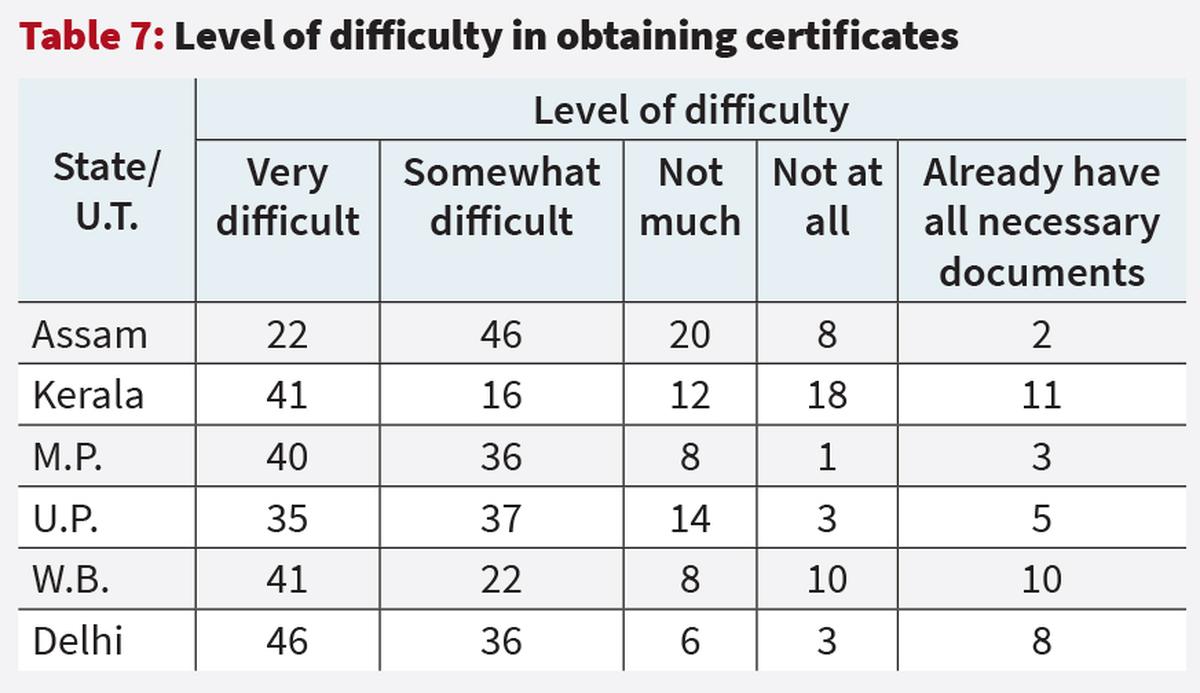

In Kerala, four in 10 believe they would not be able to obtain the certificate, and in Madhya Pradesh, over one-third say the same. Even in States with somewhat higher current possession rates, such as Delhi and Assam, around one-fifth foresee being unable to comply. Difficulty in obtaining such certificates is most pronounced in Delhi (46% “very difficult”), followed by Kerala (41%), Madhya Pradesh (40%), and West Bengal (41%). Very few in any State report already having all necessary documents (Table 7).

Availability of documents asked by EC

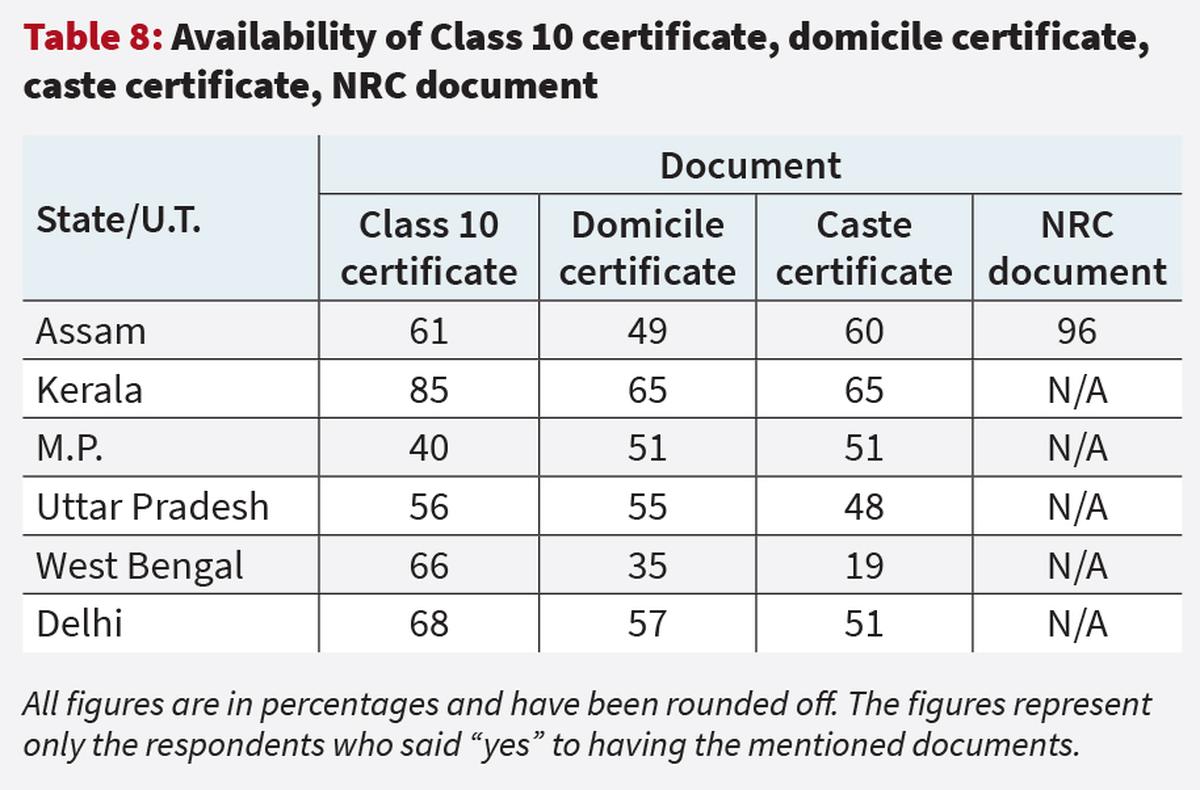

When looking at other forms of identification, possession of educational and domicile-related documents varies sharply across States. The Class 10 certificate is most common in Kerala (85%), followed by Delhi (68%), West Bengal (66%), and Assam (61%). Uttar Pradesh is slightly lower at 56%, while Madhya Pradesh records the lowest share (40%). Domicile certificates show a similar disparity. The highest reporting is in Kerala (65%) and the lowest in West Bengal (35%), with Delhi at 57%, Uttar Pradesh (55%), Madhya Pradesh (51%), and Assam slightly lower at 49%. Caste certificates range from 65% in Kerala and 60% in Assam to just 19% in West Bengal, with about half of respondents in Madhya Pradesh (51%), Delhi (51%), and Uttar Pradesh (48%). National Register of Citizens documents are only relevant in Assam, where possession is near-universal (96%) (Table 8).

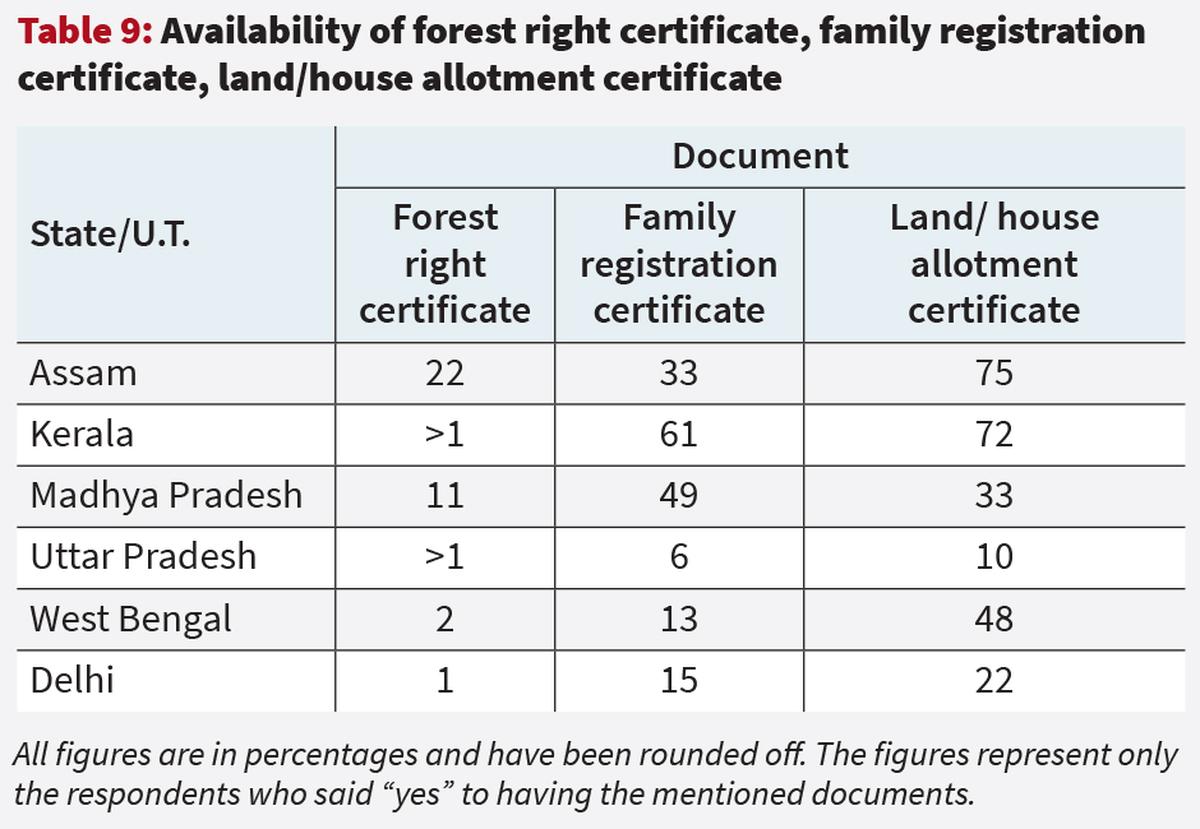

Special-category documents such as forest rights certificates, land allotment certificates, or family registration certificates are unevenly distributed. Assam and Kerala show higher possession of some of these, while Delhi and States such as Uttar Pradesh have minimal coverage, implying that these cannot serve as universal substitutes (Table 9).

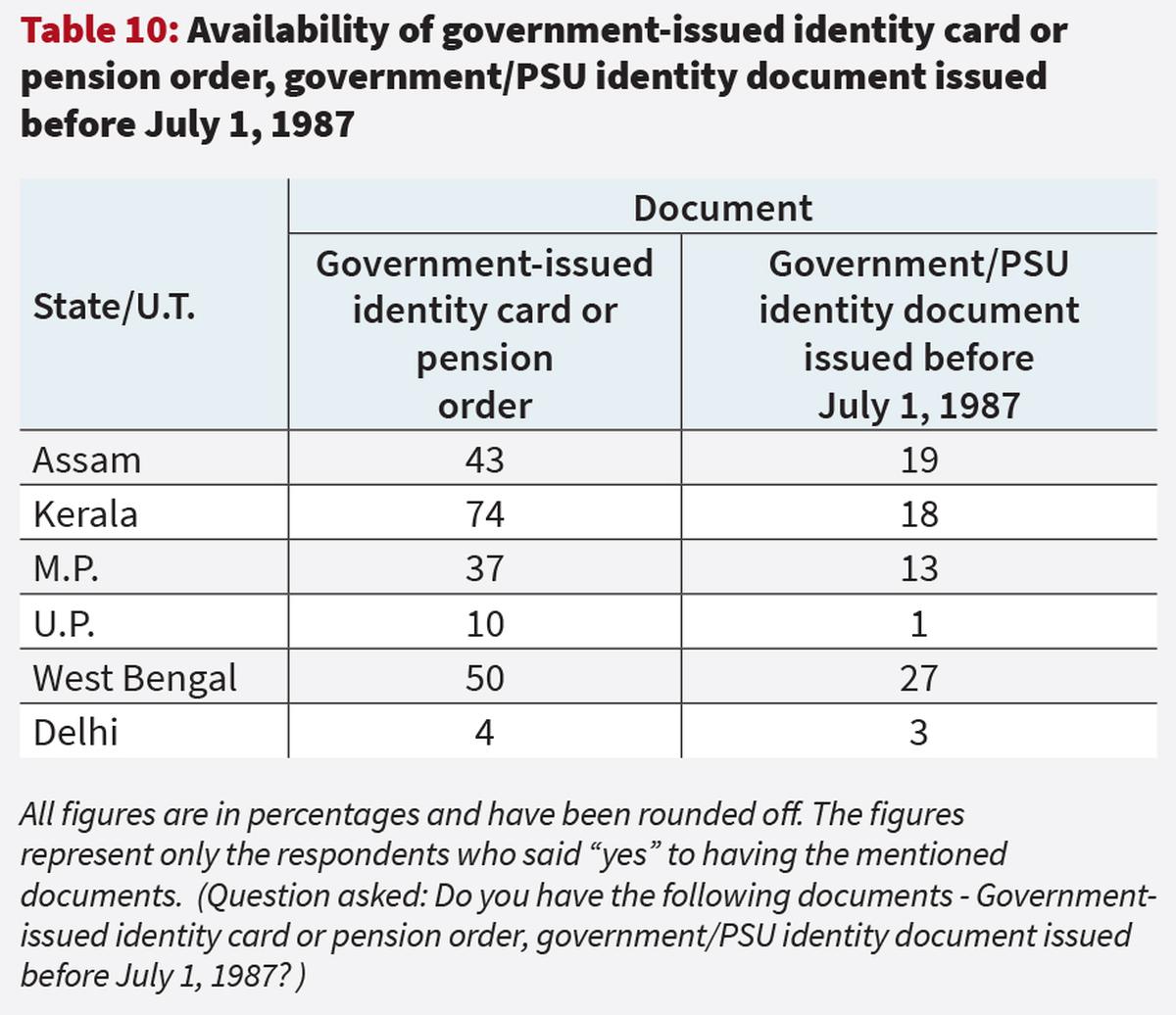

Government-issued identity cards or pension orders are most common in Kerala (74%) and West Bengal (50%), while it is 43% in Assam and 37% in Madhya Pradesh. Its possession is extremely low in Uttar Pradesh (10%) and Delhi (4%). Pre-1987 government or Public Sector Undertaking (PSU) identity documents are scarce in all States, with West Bengal recording the highest at 27%. followed by Assam (19%), Kerala (18%), Madhya Pradesh (13%), Delhi (3%) and Uttar Pradesh (1%) (Table 10).

Overall, the possession of most documents varies sharply by State. Aadhaar is the only exception, being near-universal and consistent across regions, yet it was excluded by the EC from use in the SIR exercise in Bihar. This exclusion could create a significant barrier for voters, particularly in States where alternative documents are rare, region-specific, or unevenly distributed, making a fixed, nationally applied SIR-eligible list risk disproportionately disenfranchising certain populations.

More difficult if born after 1987

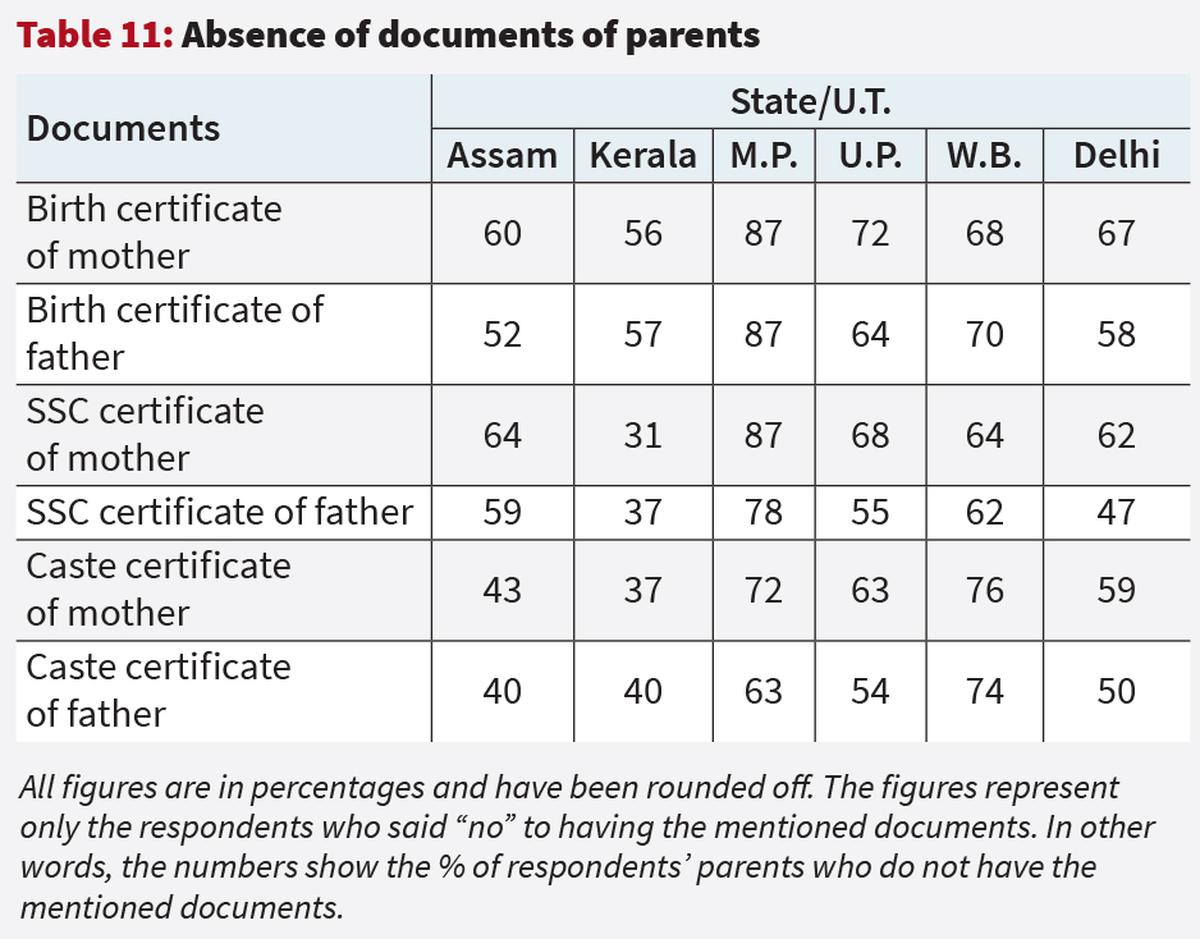

The absence of parental birth certificates is especially high in Madhya Pradesh (87% for both parents) and significant in Uttar Pradesh (72% mothers, 64% fathers) and West Bengal (68% mothers, 70% fathers). Assam and Kerala have comparatively lower absence rates, around 56% to 60% for mothers and 52% to 57% for fathers, but still represent more than half of the respondents. SSC certificate possession shows a similar pattern: Madhya Pradesh again records the highest absence (87% mothers, 78% fathers), with substantial gaps in Uttar Pradesh (68% mothers, 55% fathers) and Assam (64% mothers, 59% fathers). Kerala stands out with far lower absence for mothers (31%) and fathers (37%). For caste certificates, the highest absence is in West Bengal (76% mothers, 74% fathers) and Madhya Pradesh (72% mothers, 63% fathers). Assam and Kerala again record relatively lower absence rates (around 37% to 43%). (Table 11).

Overall, the data show that in many States, large numbers of people lack these parental documents, particularly in Madhya Pradesh and parts of Uttar Pradesh, posing a serious obstacle in the SIR exercise, where such documents may be required to establish eligibility.

Challenge of inclusivity

The above findings point to some important issues. As part of updating the electoral rolls and ensuring that errors of commission and omission are avoided, it is crucial that the review process offers a solution to the challenges faced rather than adding to the complications. Firstly, it is clear from the survey undertaken that there is significant variation across States on individuals having the documents required under the current SIR process. Taking forward the exercise within the current framework of requirements could pose a serious challenge for many of those who have a legitimate right to be part of the voters’ list.

The challenges in this regard are on account of multiple factors — the capacity of the Indian state (government authorities in general) to make available such documents and the inherent limitations in the record-keeping function, multiple barriers faced by individuals to secure the required documents and the inability to produce documents that needed to have been collected by the previous generation. While cleansing of the electoral rolls is important, the exercise, as it is currently being undertaken, is likely to lead to the deletion of many legitimate names on the grounds that they are unable to provide the necessary documents. Above all, the data here draw attention to the most critical dimension — citizens’ access to and possession of many documents being very limited. It then becomes about the willingness of and special efforts by government authorities to include all citizens in its record-keeping function.

Suhas Palshikar taught political science and is chief editor of Studies in Indian Politics; Krishangi Sinha is a researcher with Lokniti-CSDS; Sandeep Shastri is director-Academics, NITTE Education Trust and national coordinator of the Lokniti Network; and Sanjay Kumar is professor and co-director, Lokniti-CSDS