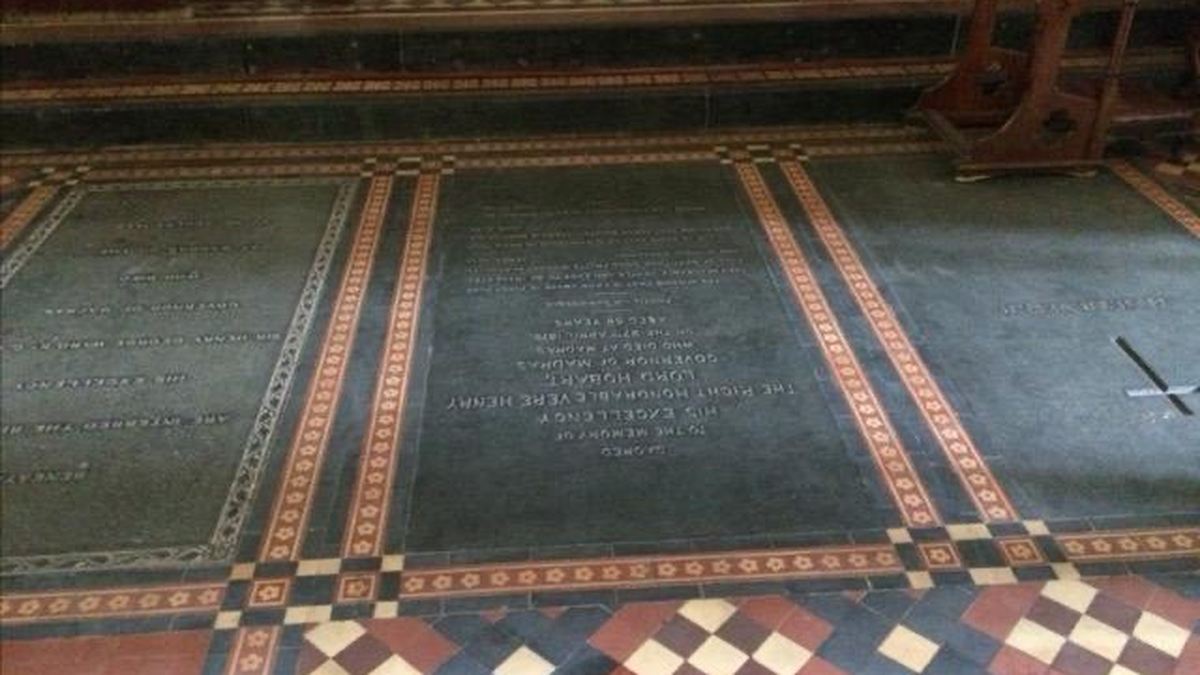

Pigot was reinterred in a position of honour near the altar and a simple black stone slab inscribed with a cross and the legend ‘In Memoriam’ was placed over it.

| Photo Credit: V. Sriram

Madras Week can be quite exhausting, but it is also a learning experience. Among my speaking assignments this year was one on gems and jewels of Madras. I dwelt on the usual suspects – Yale and the rubies, Samudra Mudali and his corals, Thomas Pitt and what became the Regent diamond, and the story of the Orlof, thought at one time to be stolen from Srirangam but now more or less agreed as being the Great Mogul Diamond. But it was when I reflected on the Pigot diamond that I realised that the stone and its owner met with similar fates.

George, first Baron Pigot, was Governor of Madras twice and in both tenures his corruption and greed were such that it even surpassed Clive’s. It is just that, unlike the latter, he did not live to tell the tale. Pigot joined the East India Company in 1736 when he was just 17 and rose to become Governor of Madras in 1755. Having presided over the siege and decimation of Pondicherry, he returned to England in 1763 where he was elevated to the peerage, acquired a stately home and became a member of Parliament. In 1775 he was back as Governor of Madras, this time to arbitrate between the Thanjavur Raja and the Nawab of Arcot. In this, probably bribed heavily by the Raja, he championed his cause, much to the irritation of his council. He was deposed, sent off to St. Thomas Mount and died there under mysterious circumstances.

Pigot acquired a diamond of 100 carats at the end of his first tenure here and took it back to England, where it was in the custody of his brothers and sister. The Governor’s death in 1777 meant they inherited it, for he had died a bachelor with a brood of illegitimate children who had no claim to the stone. The task of selling the 100-carat stone, polished down to 48 cts, was no easy task. It was unsold even at the turn of the century and a lottery was finally announced to finance the purchase, estimated at 24,000 pounds. By 1804 it had changed hands again and was now with a jeweller firm who tried to get Napoleon interested in it.

The stone remained in France without payment being made when Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Several lawsuits later, it was returned to the firm of jewellers in England who, sometime in the 1820s, succeeded in selling it to the Khedive of Egypt. The diamond vanished thereafter and has never been heard of again. There have been speculations that it is the Spoonmaker’s Diamond, now on display at Topkapi Palace, Türkiye, but this has been dismissed by experts.

Pigot’s grave too remained a matter of mystery for a century. Then, in the 1880s, the flooring of the Church of St. Mary’s in Fort St. George was undergoing repairs and an unmarked grave complete with skeleton was found under it. The matter was referred to the then Governor of Madras, the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos and he declared that it was the body of Pigot. It was solemnly reinterred in a position of honour near the altar and a simple black stone slab inscribed with a cross and the legend ‘In Memoriam’ was placed over it. It remains there, keeping company with other colonial governors such as Sir Thomas Munro, Lord Hobart and Sir George Ward. You cannot miss it.

The question remains, is the skeleton really Pigot’s? If not, then he too remains buried somewhere, just like his diamond.

(V. Sriram is a writer and historian.)

Published – August 27, 2025 08:20 am IST