We have not found an efficient solution to functioning public toilets in India. Over 11 crore household latrines and 2.23 lakh community complexes have been built under SBM(G), according to the Ministry of Jal Shakti (March 2023). Since then, many more have come up. Toilets also exist at bus stops, railway stations, airports, and public-use areas. Yet problems remain: who maintains them? Who cleans them? Do users leave the restroom clean for the next person?

This brings us back to our cultural lineage. What did Indians do for centuries before the Western toilet? How have other nations addressed the issue?

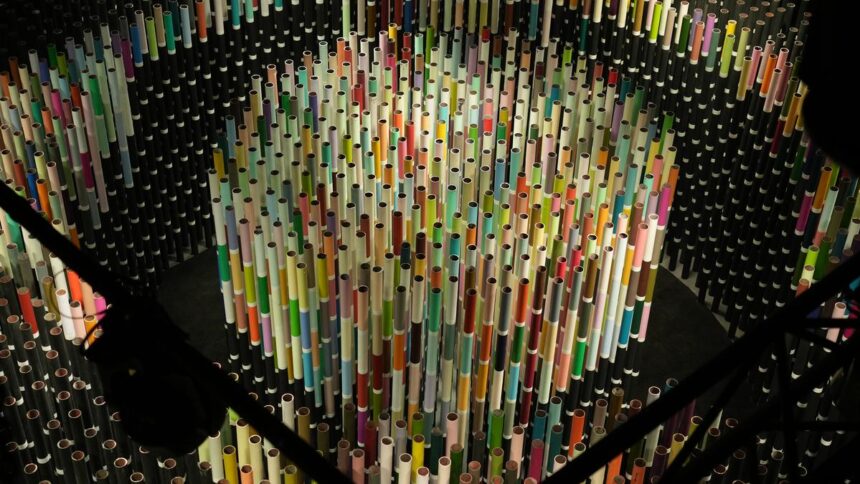

Fumikiko Maki’s design for The Tokyo Project at Ebisu East Park. View of multipurpose toilet cubicle.

| Photo Credit:

The Tokyo Project

Retired educator David Prince and his wife Dixeena, visiting Norway, were surprised by the ‘long-drop toilet’ — a pit 20–30 feet deep, with no flushing required. “Norwegians love trekking, and lodges are built around environmental principles,” says Prince. “You walk kilometres, there are no motorable roads, and while the lodges are expensive, facilities are basic: bunk beds, shared showers, and outdoor toilets with no heating. Yet Norwegians find this normal.”

Bathrooms at Nilaya Anthology, Mumbai with in-situ counters and mosaic tile walls.

| Photo Credit:

Soumya Keshavan

The Princes had to dress up warm and walk across to reach the outdoor dry toilet. Yet for Norwegians, minimal impact on nature outweighs comfort. No one complains about paying high rates without attached bathrooms. This, perhaps, is the clue to good toilet design: cultural sustainability.

Anxiety of public toilets

Public toilets in India are often associated with odour, wet floors, and lack of cleanliness. On my walk around Kodaikanal Lake, I pass a gleaming e-toilet cubicle, next to a garbage dump. Marketed as “smart” and self-cleaning, it was locked; a young man told me he had urinated behind it.

At Chennai airport, Deputy GM (Ops) AAI, Bobby Dorin describes challenges: heavy footfall that does not allow for deep cleaning, lack of user hygiene, and the mystery of perpetually wet floors. Many users splash water everywhere, even washing their feet, while design rarely separates wet and dry areas. While the restrooms today have anti-skid, easy-to-clean floors and planned ventilation, Dorin notes that it would be a value add to have ergonomic, PRM-friendly restrooms with grab bars and touchless fixtures.

Outside view of log cabin of long drop toilet in the woods, Norway.

| Photo Credit:

David Prince

InKo Center Director Rathi Jafer who travels extensively and is a connoisseur of design, quotes Skytrax’s inaugural World’s Best Airport Washrooms award, 2025 — Singapore’s Changi Airport (SIN) tops the list followed by Tokyo’s Haneda Airport (HND).

Jafer, who has visited four of these toilets, says, “Toilet design must balance function and aesthetics. Not over-gizmo’d, but clean, odourless, with dry space, clear graphics, and all basic facilities. Regular cleaning is key. Ultimately, civic sense matters most — everyone must leave the facility clean for the next.”

Bathrooms reveal the culture of a society. “I remember reading how Terence Conran (a British designer, restaurateur, retailer and writer) preferred bathrooms in white — you go there to clean yourself. This stayed with me,” says interior designer Soumya Keshavan. But she found that at Mumbai’s Nilaya Anthology, a newly opened luxury design destination in India, terrazzo floors and counters in celadon with pink fittings made a striking impression. In Bangkok’s Jim Thompson store, thoughtful use of local wood left another lasting memory.

Interior view of a minimalistic dry pit toilet made of natural wood, Norway.

| Photo Credit:

David Prince

Can such mindful design change public toilet behaviour? It brings us to The Tokyo Toilet, a celebrated experiment in restroom design.

In 2022 at Harvard Graduate School of Design, Japanese entrepreneur Koji Yanai spoke about his ‘The Tokyo Toilet’ project, funded by the Nippon Foundation. Inspired by his family enterprise Uniqlo’s motto, Made for All, Yanai wanted toilets that embody inclusivity and hospitality, especially for the 2021 Paralympics. In 2020, he commissioned 16 renowned architects and designers, including Pritzker winners Tadao Ando and the late Fumihiko Maki, to design 17 toilets in Tokyo’s Shibuya ward.

Japanese architect Shigeru Ban’s design is famous: see-through glass cubicles that turn opaque when locked. Yanai emphasised that toilets are unavoidable — unlike meals, they cannot be skipped. Japanese culture prizes cleanliness, and these toilets are cleaned three times daily.

Pink-coloured wash closet with custom wall shelf detail finished in situ at Nilaya Anthology, Mumbai.

| Photo Credit:

Soumya Keshavan

The project even inspired Wim Wenders’ film Perfect Days, about Hirayama, a meticulous toilet cleaner whose quiet dignity elevates his profession.

Shifting habits

Traditionally, Indian toilets were detached from the home — basic squat pits with a tap. From this minimalist setup, we have shifted to Western-style wash-closets, faucets, hand dryers, and paper towels. Yet many still associate cleanliness with washing the entire floor, leaving public toilets wet and slippery. Responsibility is deferred: someone else will take care.

The public toilet at Nayara’s bunk is neatly designed with good fittings and a separate handicapped toilet.

But there are exceptions. At DakshinaChitra near Chennai, despite heavy school visits, toilets remain clean. Strong management and cultural reinforcement help.

In the newsletter behind the genesis of Liquid, VitraA’s Global Design Director, Erdem Akan, recalls his “favourite bathroom” as simply a picture of nature: trees, river, landscape. “Art, culture, and nature must be part of a bathroom,” he says. Perhaps this is the direction India needs — toilets that blend cultural context and nature, artful reminders of cleanliness, and design that accommodates diverse users.

Liquid, VitrA by Tom Dixon.

| Photo Credit:

Soumya Keshavan

Putting culture into context

Across Norway, Turkey, Japan, and India, toilets reveal not just sanitation practices but cultural values. Norwegians prioritise nature so much that they build pit latrines in the mountains, while the Turkish embrace modular designs, balancing tradition and modernity. Japanese hospitality is at the core of its inclusive and artistic toilet designs. India’s struggles with the toilet as an indoor space after centuries of using the outdoors and simple squat toilets reflect how design needs to consider our inherent cultural sensibilities and inherited behaviour. If India is to solve its public toilet problem, design must go beyond hardware. We need to design mindfully, depending on the type of public space, appropriate to each context, rather than rush to adapt universal typologies. We must embrace culture, cleanliness, and inspire civic cooperation through design that speaks to our people. Only then will toilets — our most basic need — become spaces of comfort rather than anxiety.

The writer is a brand strategist with a background in design from SAIC and NID.