In early August, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that imports from India to the U.S. will be charged tariffs at 50%. This includes a 25% penalty for India’s oil purchases from Russia. The U.S. tariffs bring challenges to the Indian economy. What are the policy options for India?

Tariffs are the taxes levied on imports from other countries. The average tariff imposed by the U.S., the world’s largest export market, was 2 to 3% for two decades until 2024. All that has changed with President Trump announcing a steep hike in U.S. tariffs on April 2 this year.

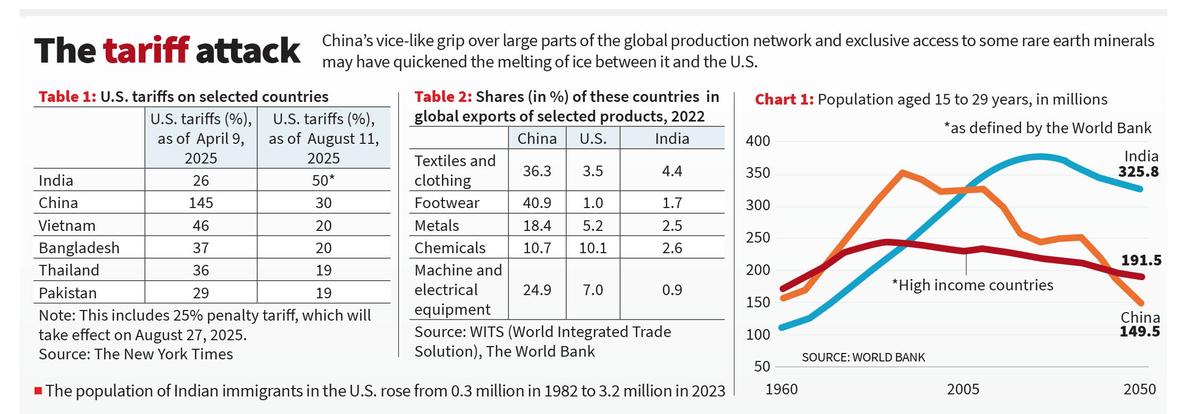

If the 50% tariff rate imposed on India takes effect, a shirt that an Indian firm sells for $10 will cost as much as $15 for the U.S. consumer. The tariffs on goods from India are higher than the tariffs the U.S. has imposed on India’s export competitors (Table 1). Therefore, a similar shirt shipped from Vietnam or Bangladesh will cost $12 or less, making Indian products uncompetitive. When Mr. Trump launched the tariff war in April this year, his fury was directed mainly at China, which was charged with tariffs of 145%. But subsequently, the two countries agreed to cool off their animosities, and the U.S. tariffs on China have now come down to 30%. Astonishingly, India, a close U.S. ally, is now the country (with Brazil) threatened with the highest U.S. tariffs.

For India, the dollars it earns by selling textiles, pharmaceuticals, software services, and other products to the U.S. are critical for bridging the country’s external trade deficit. Mr. Trump’s tariffs may lead to job and income losses in India, at least in the short run. At the same time, in exchange for reducing tariffs, the U.S. is seeking greater access for its agricultural products, especially dairy, in the Indian market. This will in turn have adverse impacts on Indian farmers.

Nature of China’s influence

The unfolding tariff war shows that low wages alone will not give a lasting competitive advantage to a country in the export market. China’s strengths emerge from its enormous scale, massive infrastructure, and growing technological capabilities. China has established an unassailable lead in several industries. Its shares in global exports are 36.3% in textiles and clothing and 24.9% in machine and electrical equipment. The corresponding shares for India are 4.4% and 0.9% respectively (Table 2).

China’s vice-like grip over large parts of the global production network and exclusive access to some critical materials such as rare earths may have quickened the melting of ice between it and the U.S. Moreover, further uncertainty and tariff escalations with other countries may derail plans by global companies to diversify their investments away from China and do more business with India and Vietnam.

If left with low wages as its only bargaining chip, India will remain on the periphery of global business, ever to be pushed by lower-cost suppliers and by the whims of tariff administrators of rich countries. Despite their early starts, India’s IT and pharmaceutical industries tread unsteadily in low-value activities due to their underinvestment in research and development.

From producer to consumer

A significant source of demand for export-driven economic growth in China and other developing countries over the last few decades has been consumers in high-income countries in the West. However, the purchasing capabilities of developed countries have been going downhill for a while due to their ageing populations and growing inequalities. With rising tariffs and protectionism, the markets in the West will also be less open.

This means that future economic growth must be built around the demand from the home markets of countries such as India and China. The populations of these countries will have to transform themselves from being low-cost producers to producers and consumers simultaneously — from being servers left with only crumbs from growth to diners who occupy the high table of capitalist progress. Such a transformation can occur only with sweeping economic changes. Wages and incomes must rise quickly in India. High-value-adding economic activities based on technology and knowledge must replace growth extracted exploitatively from labour.

The role of young India

Those who doubt Indians’ ability to partake in growth derived from skills and talent need only to look at the record of Indians in the U.S. over the past half-century. The immigration to the U.S. of engineers, doctors, and other professionals, most of them trained in India’s public universities, has grown steadily since the 1970s. Approximately, a third of the graduates from Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) migrated abroad, most of them to the U.S., through the 1970s and 1980s. The population of Indian immigrants in the U.S. rose from 0.3 million in 1982 to 1.3 million in 2000 and 3.2 million in 2023. Although still only 1% of the U.S. population, Indian immigrants have a disproportionately higher representation in higher education and research and as entrepreneurs and corporate leaders. The ‘brain circulation’ they set in has contributed to the U.S.’s continued global dominance in technology and innovation.

Today, one out of every five young people in the world lives in India. At a time when the youth population is declining not only in high-income countries but also in China, the multitude of its young will be India’s trump card (Chart 1). Indians in the age group between 15 to 29 years and enrolled in secondary schools or colleges number approximately to 120 million, which is as big as the population of Japan. If accompanied by appropriate policy interventions to enhance their skills and training, these young Indians could become the movers and shakers in the emerging knowledge economy.

The U.S. administration will be wise enough not to underestimate India’s strategic importance by factoring in only the relatively small size of its goods trade. If young Indians are turned away from the U.S. due to visa and job restrictions, the U.S. will be the bigger loser in the long run.

As the battle on trade and tariffs rages on, India’s best defence will be its young people, their sheer numbers and the promise they hold. The home market they generate will be large enough to compensate for any dip in export earnings, provided jobs and incomes expand fast. Greater public expenditures on health and education, and a renewed focus by domestic businesses on innovation will be critical for unleashing the strengths of India’s young as a shield against growing global turbulences.

Jayan Jose Thomas is a Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi

Published – August 20, 2025 08:30 am IST