Rajinikanth is worthy of every bit of praise. Surviving, let alone succeeding, 50 years in the Tamil film industry deserves a celebration. But for what specifically? For acting in around 170 films in different languages, his screen charisma, his politics, his impact on the lives of his fans?

Fifty years seems just like yesterday when Rajini’s first film, Apoorva Ragangal (1975), launched him into history — although he was not the hero. He remade himself to suit the needs of others. His name was changed, he learnt a new language, and put on a new persona that was dictated by filmmaker K. Balachander’s vision of what he saw in Rajini.

Five decades ago, he started the journey of becoming a cult figure by legitimising rebellion, making it possible to talk about desires that were taboos, speaking for those who were invisible and on the margins of society, and began the first steps towards fashioning an image of himself. His latest film, Coolie, which released last week, commemorates these years. Much has changed, but much remains unchanged. What has not changed is that like back then, he is still trying to put on a new persona, trying to be what he is not.

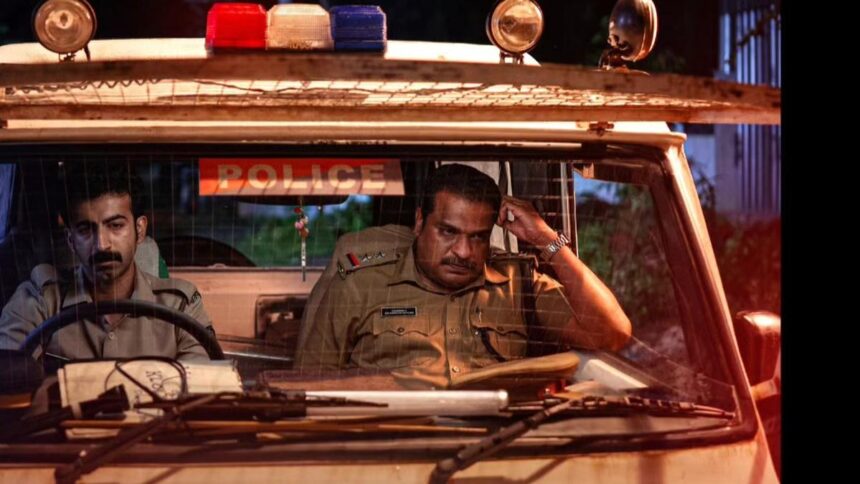

A still from Coolie

It is said that the greatest fear of superstars is ageing. While we celebrate their longevity, they seem to live in mortal dread of it. The real life picture of a bald-headed Rajini makes him look like our beloved uncle. In Coolie, he has a head full of lush hair and fights like a young man, although his eyes betray him. The same powerful eyes that Balachander commented on 50 years ago now lie hidden in deep sadness, perhaps reflecting the pain that he still has to do films like this in the name of superstardom.

Perfecting the grey figure

Rajini was never defined by his body. He was dark and slight, more like a Bengaluru bus conductor — which he was before he became an actor. He was a Marathi speaker too, who spoke Tamil with a different lilt. Rajini’s strength and power came from what he spoke and stood for. He personified a simple but powerful truth: that those who are poor and disadvantaged have a greater moral sensibility than those who possess wealth and power. The vegetable sellers on the pavement, the daily wage earners, the coolies as well as the autorickshaw drivers exhibit far greater moral qualities than do feudal landlords, rich entrepreneurs or powerful leaders.

He was loved because he embodied that grey figure between socially acceptable behaviour and individually regressive one. He could be charming even when he was being politically incorrect. His audience loved him because they knew that he was a moral being at his core.

Fans dance during a screening of Rajinikanth’s Coolie

| Photo Credit:

AFP

The coolie theme that was so crassly abused in his new film was one that invoked deep feelings in the working class whose voice he represented in films such as Mullum Malarum (1978, a villager in conflict with an urban engineer), Baasha (1995, an auto driver), Muthu (1995, a servant under a feudal landlord), and more recently, in Pa. Ranjith’s hit film Kaala (2018) where he fights for slum dwellers. The younger Rajini acted like an older man, wiser, responsible, more socially attuned, and one who produced hope.

Moral ambiguities

Fifty years on, Rajini’s morality has aged. He is not able to hide this even if he succeeds in camouflaging the ageing of his body. When he played a gangster in Thalapathi (1991), there was a sense of moral code in the world of criminals. But in Coolie, Rajini’s moral sense disappears when he joins a young woman in a criminal act to justify making money to pay the fees for the medical education of the woman’s sisters. He is not the Rajini that we saw in Bhairavi (1978) or movies like Aval Appadithan (1978), which catalysed a larger discussion on women’s rights and roles in a society.

A still from Thalapathi

Rajini was as famous for his dialogues as for his cigarette tricks because those dialogues did not age. They did not need an old man, trying to look young with a mop of hair, to deliver them. Rajini converted these dialogues in movies such as Arunachalam (1997), Baasha and Padayappa (1999), into social slogans.

As long as Rajini speaks for the rights of the oppressed and the marginalised, his physical age does not matter. Being old is exhibited not in the way we walk or fight, but in the way we think, in the energy we have to fight for the benefit of others, and in the hope that we bring.

Rajini, while still physically explosive on the screen, has aged mentally and morally, at least in his last few films. He seems to have lost the qualities that made him perennially young and relevant. We can’t blame him. Perhaps he has become indifferent and tired. Just like us.

The Bengaluru-based writer and philosopher’s new novel is titled Water Days.

Published – August 22, 2025 07:17 am IST