Grief hangs heavy in the narrow lanes of Old Ramanthapur, a working-class suburb on the eastern edge of Hyderabad. Inside the Yadav household, every corner seems to echo with the absence of 21-year-old P.Krishna, — the only son in a family of daughters, the boy everyone relied on. Days earlier, his right arm was crowded with rakhis, tied lovingly by his sisters who will now have only that memory to clutch on to.

On August 18, Krishna, fondly known among his friends as ‘Diamond’ had stepped out into the rain to fetch his father from the Janmashtami procession. Often seen in crisp white shirts, he had put on a yellow turban and scarf on the festival day. It was the first ever Krishna Shobha Yatra in their neighbourhood. Until now, locals say, the festival revolved around the traditional utti or utsavolam, in which clay pots filled with butter or sweets were smashed by youths forming a human pyramid. The grand procession was meant to add visual flourish and attract youth to the celebrations.

By midnight, he and four others lay lifeless on the road. The nine-foot chariot they were pulling had brushed against a sagging high-tension wire near RTC Colony. The current tore through the men in seconds. Krishna died instantly, along with Rajendra Reddy (48) of Ravindra Nagar Colony, Srikanth Reddy (35) of Sharada Nagar, Rudra Vikas (39) of Habsiguda and Suresh Yadav (34) of Old Ramanthapur.

His sister Ramya, who had stayed back at home after Raksha Bandhan, remembers him urging her not to leave for her in-laws: “Just two months ago, he had planned my wedding down to the smallest detail. He assured me that though he is younger, he would always take care of our parents. No matter what [compensation] the government gives us, they can’t bring him back.”

“Within seconds, it was all over. My son had come to take me home in the rain. He wanted to help move the chariot,” recalls Raghu Yadav, Krishna’s father, his voice breaking. “He was our support. But he is gone.”

The loss rippled across households. Rajendra Reddy’s wife and two school-going children are left behind. Srikanth Reddy’s teenage children must now grow up without the man they relied on. The morning after the incident, Suresh Yadav’s family had returned to their native place with their infant daughter, their home in Ramanthapur locked and silent. Neighbours say he was the sole breadwinner.

Among the survivors was Armed Reserve head constable V. Srinivas (55), a thick bandage wrapped around his head and his chest still marked from the CPR that saved him. “I have been friends with Vikas, Srikanth and Rajender Reddy for over a decade. We even took photos together before the procession began. When the Gypsy ran out of fuel, we started pulling the chariot ourselves. I was holding it from the back when there was a sudden spark. I collapsed. The next thing I knew, I was in the hospital. I lived, but my friends did not.”

Others injured included Ganesh (21) of Golnaka, Surva Ravindar Yadav (30) and Mahesh (27) of Old Ramanthapur. Mahesh has since been discharged, but the rest are still undergoing treatment.

In the aftermath of the electrocution deaths, the Electricity department scrambled to cut wires hastily and arbitrarily, leaving a heap strewn on the road.

| Photo Credit:

G. Ramakrishna

But Ramanthapur was not the only tragedy. Within 24 hours, Hyderabad saw two more fatal electrocutions. In DD Colony, about 2.3 kilometres from Ramanthapur, labourer Ram Charan Tej (18) died while erecting a 15-foot pandal for Ganesh puja, suffering a fatal head injury. The next morning in Bandlaguda, around 16 kilometres from Ramanthapur, Tony (21) and Vikas (22) died when the Ganesh idol they were transporting touched a 33-kv line. Their friend Akshay, 23, escaped with injuries.

Eight lives lost in less than 48 hours. Since January, more than a dozen people across Hyderabad and surrounding districts have died in similar accidents — a boy near an Eidgah ground in Khairatabad, two men pulling down a signboard in Habsiguda and workers tying banners or plucking mangoes near live wires.

The series of electrocution deaths jolted the government into action. Within 24 hours, Deputy Chief Minister Mallu Bhatti Vikramarka, who is also the Minister of Energy, ordered a fast-track shift to underground cabling in Hyderabad. He also directed the removal of unauthorised cables from electric poles, warning of strict action against operators. The move echoed Chief Minister A.Revanth Reddy’s earlier call for underground networks and followed Mr.Bhatti’s study of Bengaluru’s cabling model.

The Uppal police of Rachakonda booked a case of accidental death and started a probe. Meanwhile, IT Minister D. Sridhar Babu announced ex-gratia of ₹5 lakh for each of the bereaved families and said the government would bear the entire medical expenses of those injured.

Yet beneath the urgency of these announcements lies a more complicated reality. Hyderabad’s skyline of poles and wires is the outcome of years of neglect, weak regulation and blurred responsibility. “In a built-up city, undergrounding is disruptive and expensive,” says architect Shankar Narayan. “Smart poles are a better alternative, where electricity, internet and other utilities are integrated. Along major roads, underground cables may work. But in narrow bylanes, smart poles, like those used in Japan, are easier to maintain and can even generate revenue if properly regulated.”

He adds that the electricity utility could even generate revenue by regulating this. “Internet service providers string wires haphazardly on poles, and when they are cut, households are left without connectivity. Governments should involve planners and architects before rolling out such projects,” he argues.

A knee-jerk reaction

Instead, haste triggered fresh chaos. Telangana State Southern Power Distribution Company Limited (TGSPDCL), reeling from criticism, began hacking down overhead cables across Hyderabad. In the process, it left lakhs digitally paralysed. The Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI) called the abrupt cable-cutting move “indiscriminate and aggressive.”

Social media was soon flooded with photos of severed wires piled on pavements. Office work was stalled, students missed deadlines and homes fell into sudden silence. “Without internet, all our high-end devices are just bricks,” says Rahul Kumar, who gave up work to watch a movie with colleagues.

College students, struggling on patchy mobile data, fumed. “I had a deadline for my project submission and missed it as there was no Wi-Fi. And they tell us Hyderabad is becoming a smart city,” rues engineering student Sridhar.

Even daily routines were upended due to the balckout. “Our smart TV went blank. My daughter asked if the internet had gone on strike,” says Arvind, a software engineer from Kukatpally.

A senior official in the Department of Electrical Inspectorate admits that Hyderabad’s poles were never designed for the burden they now carry. “They were meant for power and service lines. Today they carry a messy bundle of electric and broadband cables, often indistinguishable from one another. Reckless pulling of network cables can disturb an electric one, and in some cases, even turn a data line into a conductor,” the official avers.

The risks, he explains, build up slowly but fatally. Constant tugging and overloading weaken the poles, while the friction erodes the insulation on power lines. “Even without a direct fault, the way these cables are fastened and dragged eats into the lifespan of our network. It is a slow, invisible erosion of safety. A single break in sheathing or prolonged contact with a signal cable can unleash a lethal charge,” he says.

Eyewitnesses in the Ramanthapur case recall seeing a dangling signal line brushing a high-tension wire — the moment the chariot became electrified, causing the five young men to collapse within seconds.

Such incidents, the official points out, underline not just technical flaws but the absence of clear oversight. Broadband operators, mostly private players, string lines across power infrastructure with little oversight. Permission is meant to come from both municipal authorities and the power utility, but in practice it is rarely sought.

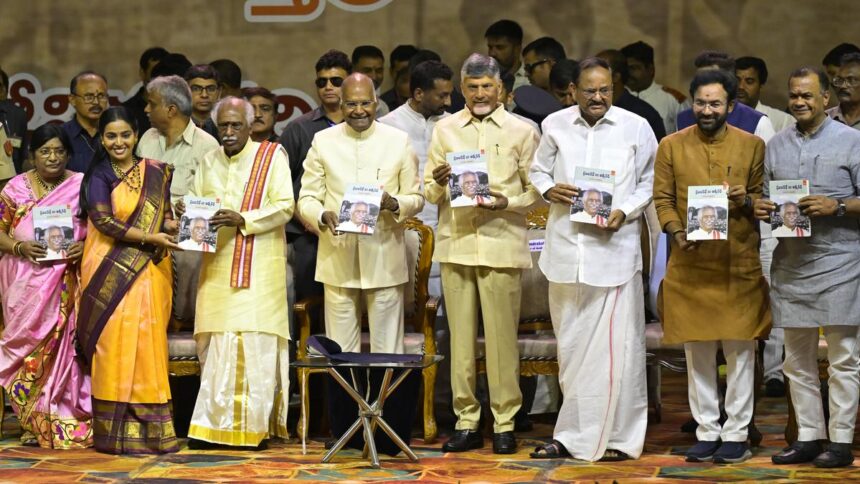

A man rides past a condolence poster of the five men electrocuted when their chariot touched a sagging high-tension wire during the Krishna Janmashtami procession in Hyderabad’s Ramanthapur on August 17 night.

| Photo Credit:

G. Ramakrishna

According to him, both the Central Electricity Authority regulations and Indian Standard IS:1255, which lays down norms for the safe installation and maintenance of power cables, emphasise the need to keep signal and power cables separate to ensure safety and prevent interference.

Last year, the TGSPDCL had issued directives to cable operators and internet service providers to remove unauthorised lines from electricity poles. But enforcement is weak.

“Broadband providers must be brought under a regulatory framework, with accountability equal to that of the power network. Unless their networks are supervised, monitored and shifted to safer routes, either physically away from the power network or into underground ducts, such preventable tragedies will repeat,” he warns.

Meanwhile, internet service providers (ISPs) argue that they are being unfairly targeted. A field worker from a leading ISP says that operators already pay rent to use electricity poles — about ₹50 monthly per wire per pole — a cost that is passed on to customers as part of subscription fee. “Of a ₹3,500 subscription for six months, nearly ₹500 goes to the government as tax. When we are already paying rent, how can we be called unauthorised,” he asks.

Under the current arrangement, he clarifies, the Electricity Department is responsible for maintaining both the poles and the cables. He also claims that optical fibre cables are insulated and safe. “We handle them with bare hands every day. There is no risk of current passing through.”

He notes that the sheer demand for broadband has driven the proliferation of wires. “Sometimes 3-4 lines hang on a single pole, sometimes 10, depending on the area. We try to have as many wires as we can on a single pole to meet demand and cut costs,” he says.

But the sudden cable-cutting drive has been crippling. “In one night, three truckloads of wires were cut from 5,000 poles in Ramanthapur alone. Across the city, more than 10 lakh users lost internet. Restoring those networks will take weeks and massive investment. But the government is turning us into scapegoats,” he says.

Technicians on the ground describe an impossible workload. “People think we just plug a wire back in and it works,” says a junior ISP worker. “After TGSPDCL’s cuts, we have to trace every line and redo the connections. Our customers are calling us nonstop, but the damage wasn’t ours to begin with. We don’t even know when we can restore service.”

Searching for safer streets

Even as operators complain of disruption, officials stress the need for deeper reforms. With the Ganesh festival days away, experts have flagged weak joints, low-grade festival wiring and risky pandal connections as potential hazards. Suggested safeguards include insulated connectors, isolating devices, regular safety audits, CCTV monitoring of power lines, and limits on idol height and structure.

In 2016, the Telangana High Court capped idol heights at 15 feet, but the order has remained largely on paper, with affluent organisers competing to stage ever-grander installations. Official warnings have fared no better.

But the broader challenge is structural. Hyderabad’s wires are not just a tangled mass overhead; they are entangled in bureaucracy, split between civic bodies, discoms, private operators and State agencies, with no single authority taking complete responsibility. For grieving families in Ramanthapur and beyond, however, debates over underground ducts, smart poles and regulatory gaps hold little meaning. Their plea is stark: no more lives should be lost to a system so dangerously unmanaged.