The smell of incense lingered in the air, the sound of drums and chants rising, as residents of Goske Rajaiah (GR) Colony in Telangana’s Kamareddy town prepared for Ganesh Chaturthi on August 27. Then, without warning, the celebrations fell silent. By noon, the colony was unrecognisable, echoing with cries for help.

“Everything changed in just 30 minutes,” recalls Hajiwar Srinivas, president of the residents’ association at GR Colony. Around 10.30 a.m., a furious surge of water from the overflowing Kamareddy Pedda Cheruvu burst into the colony from both sides of the stream. By 11 a.m., every ground floor was under water. A morning of prayers had turned into a desperate scramble for survival, as families clung to rooftops and upper floors, watching helplessly while floodwaters swallowed their homes.

For three days — from August 27 to 29 — unprecedented rains battered Kamareddy town and district, submerging several colonies and villages. Families were forced to abandon their houses and flee with whatever they could carry, as personnel of the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF), State Disaster Response Force (SDRF) and Emergency Services Department, assisted by local volunteers, waded in for rescue.

To reach Kamareddy from the National Highway-44, one must turn onto the old highway — a two-lane stretch leading seven kilometres into the district headquarters, 110 km from State capital Hyderabad. It was here, along the small stream, running parallel to the bypass, that calamity struck. That Wednesday, the stream received flash floods so fierce that three colonies — GR Colony, Teachers Colony, and Housing Board Colony — along with the ST Residential School in Sarampalli, were swallowed whole.

Within minutes, floodwaters surged into streets and homes, forcing residents and schoolchildren alike to look for shelter on higher ground. Many remained trapped until 11.30 p.m., when rescuers finally reached them.

The middle-class residential pockets on both sides of the bypass road — home to Kamareddy’s 1.16 lakh population — bore the brunt. With most houses built as modest G+1 or G+2 structures, the ground floors became traps. Days later, fear still lingers. Even the sight of a cloudy sky is enough to send shivers down the spines of residents.

“We are vacating this rented home and moving to another colony nearby. It is not safe here,” says L. Swaroopa of GR Colony, as she loads her belongings into an autorickshaw. Her family lost appliances worth nearly ₹8 lakh — a television set, laptop and furniture. Their car was swept away and later found in the stream.

Her husband Nagaraju, a car mechanic, now repairs other flood-damaged vehicles for free, even as four of his own clients’ cars lie ruined in his shed. “It will take at least five to six years to recover from this loss,” she says, her voice heavy with despair.

Videos from that day show cars parked on the stream bund being tossed around like toys. In all, 18 vehicles were reportedly washed away. Residents insist this devastation was not nature’s fury alone; they blame unchecked encroachments on the stream, which had drastically reduced its water-carrying capacity. The 128-year-old tank overflowed, worsened by inflows from cloudburst-hit upper regions, and the surplus course simply could not hold.

Chief Engineer (Irrigation) T. Srinivas admits the flow had been twice the culvert’s designed capacity. Officials are now examining the scale of encroachments that may have choked the stream.

For 65-year-old supermarket owner Bondhugula Murali, the memory is raw: “With three grandchildren, the youngest aged only 13 months, we stood on the rooftop, waiting for water and milk.”

Communication gap

His anger is directed at the lack of prior warning. While the India Meteorological Department insists a red alert had been in place for 24 hours, State officials dismiss it as a “routine alert”, or too vague to trigger adequate preparedness.

Rescue teams eventually made the difference between life and death. “Around 11 a.m., we received an alert about flooding in GR Colony,” says District Fire Officer (in-charge) S. Sandhanna. Station Fire Officer Abdul Salam and his team rushed in with rescue tenders, evacuating 240 people to safety with the help of private earthmovers. Even when one rescue vehicle overturned in the gushing waters, the staff managed to pull themselves, and others, out alive.

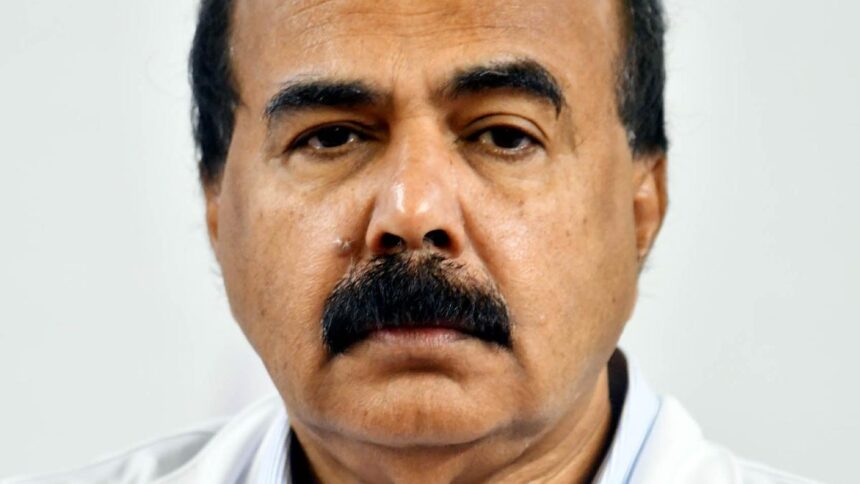

Family members of Ippakayala Vinay Kumar, a Mid-Level Health Provider, who died when a compound wall collapsed on him at his residence in BC Colony of Rajampet village in Kamareddy district during the rains.

| Photo Credit:

NAGARA GOPAL

Swift action ensured that the toll did not spiral out of control. “We could restrict the death toll to four only because of timely rescue operations,” says District Collector Ashish Sangwan. “With the help of NDRF, SDRF and emergency teams, 17 rescue missions were carried out, saving 837 people across the district, including Kamareddy town.”

Officials detailed the scale of the effort: two NDRF units, six SDRF teams and five emergency response squads fanned out across 15 locations. Among the biggest rescues were 198 residents near ESR Garden in GR Colony, nearly 300 children and staff from the ST Residential School and scores from Teachers Colony, Housing Board Colony and several inundated villages.

Yet tragedy was unavoidable. At Rajampet village, Ippakayala Vinay Kumar (28), a mid-level health provider working at Argonda Palle Dawakhana, died when a compound wall collapsed on him. “He was trying to drain the floodwater by making a hole in the wall with a digging bar,” recalls his maternal uncle Naka Srinivas. “The wall gave way instantly, crushing him.”

Rajampet mandal was the worst hit by the rains, recording 71.82 cm rainfall in just three days, accounting for 74.7% of its annual normal rainfall.

The district overall was reeling too. “Kamareddy recorded 40.7% of its annual rainfall in just three days,” Collector Sangwan notes.

Against a normal yearly average of 98.34 cm, the district was pounded with 39.98 cm from August 27 to 29. Roads caved in, crops perished, cattle were lost, and several towns and villages were paralysed.

Record-shattering rain

The scale of the deluge has already entered the record books. Multiple mandals in the district logged more than 300 mm of rain within 48 hours, placing the Kamareddy floods among the State’s top 30 historical events since 1900. Dhanya Bulla, founder of Hyderabad-based FloodGuard Solutions, which works on building climate-resilient communities, calls it “the second highest in 120 years” in terms of extreme rainfall spread across multiple stations.

Numbers underline that claim. On August 27-28, Rajampet recorded 440 mm followed by Nagireddypet at 335 mm, Kamareddy 334 mm, Sadasivanagar 319 mm, Lingampet 316 mm, Bikhanoor 330 mm and Tadwai 300 mm. Just a day earlier, Nagireddypet had received 247 mm rainfall, Yellareddy 253 mm, Lingampet 157 mm, Bhikanoor 170 mm and Rajampet 136 mm.

The 440 mm that Rajampet saw in two days now ranks among Telangana’s top 15 extreme rainfall events. But what makes it stand out is not one freak downpour but a cluster of stations simultaneously recording over 300 mm — a rarity in the State’s rainfall history.

It wasn’t a single-location extreme but a clustered extreme over Kamareddy and Medak districts, Dhanya observes.

Repairs being undertaken on the bypass road near GR Colony in Kamareddy after a portion of it was washed away in the downpour.

| Photo Credit:

NAGARA GOPAL

A senior IMD scientist explains the meteorological cocktail that unleashed such fury: an eight-kilometre-high swirl of moisture from the Bay of Bengal collided with winds from the Arabian Sea over central Telangana. The result? An average of 30 cm rainfall poured over nearly 1,000 square kilometres in a span of few hours. That translates to 10.6 tmc ft of water crashing down, drowning towns and fields alike.

But while the IMD insists alerts were issued, their public messages on social media appeared vague and routine, failing to flag the scale of what was to come.

The deluge left Kamareddy’s infrastructure in tatters. Officials have identified 886 works requiring urgent or permanent restoration. The bill is staggering — ₹37.99 crore for temporary fixes and ₹210.6 crore for permanent repairs. The damage spans every sector: 157 irrigation tanks, 116 Roads & Buildings stretches, 122 Panchayat Raj roads, 242 schools, 47 Health Department buildings, 31 electricity installations and several civic assets across municipalities.

Agriculture, the district’s backbone, was equally devastated. Floods swept through 334 villages, inundating nearly 50,000 acres of standing crops. Initial surveys recorded 1,683 acres of losses, though officials warn the final tally might be far higher. Horticulture took a blow too — 140 acres were affected, with nearly a third suffering damage beyond recovery.

“Two out of my three acres of paddy are gone,” says Dasari Bhumaiah from Polkampet village of Lingampet mandal, whose fields were drowned after the Sardha cheruvu breached. In nearby Lingampalli village, another breach at the Mallaram tank flattened entire stretches of crop overnight.

Haunting trail of destruction

Homes and livestock were not spared. A total of 1,225 houses were damaged, one of them completely. Relief assistance of ₹43.8 lakh has been sanctioned, but it does little to ease the loss. In animal husbandry, 108 cattle — cows, buffaloes, bulls, calves, sheep and goats — perished. Poultry farms were hit hardest, losing 47,570 birds in the floodwaters.

Electricity supply snapped in 38 villages but has since been restored. Temporary patchwork has helped revive 113 damaged culverts and 145 irrigation tanks, though permanent rebuilding is still pending. Roads remain fractured and bridges washed out, cutting off access to some hamlets. “Our priority is restoring connectivity and ensuring supply of essentials,” Sangwan says, stressing that encroachments on stormwater drains and streams will now be cleared to allow free water flow.

The scale of rainfall defies recent memory. Argonda station in Rajampet mandal alone clocked 44 cm. Across Telangana, 23 locations — including 10 in Kamareddy, four in Nirmal, six in Medak and the rest in Nizamabad and Siddipet — recorded more than 20 cm. It was the heaviest downpour in such a short span in the past 50 years.

Flood victim L. Swaroopa (left) from GR Colony in Kamareddy shows the damage to her TV set after flash floods swept through the area following heavy rainfall.

| Photo Credit:

NAGARA GOPAL

Amid this chaos, SDRF teams carried out risky missions, rescuing nine stranded workers at Boggu Gudise and five more from Gunkal village.

Pocharam withstands record inflow

Even century-old engineering was tested. On August 27, the 103-year-old Pocharam Project in Nagireddy mandal faced a record inflow of 1.82 lakh cusecs, nearly triple its designed capacity of 70,000 cusecs. As water overtopped and the Kamareddy-side bund showed strain, fears of a breach spread. Officials later confirmed that the structure held firm as levels receded.

In contrast, the Kalyani Medium Irrigation Project in Yellareddy mandal was not as resilient — its gates gave way under the pressure of swollen inflows.

Pocharam carries history in its stones. Built across the Allair river in Nagireddypet, it was the Hyderabad Nizam’s first irrigation project, with its foundation laid in 1917 and completed in 1922. Once designed to hold 2.423 tmc ft, siltation has reduced its storage to 1.82 tmc ft. Even today, its 1.7-km limestone bund, 58-km canal network, and 73 distributaries irrigate 10,500 acres while supplying drinking water to Kamareddy and Medak. That this relic of another era withstood the flood fury was, for many, a small miracle.

On September 4, Chief Minister A. Revanth Reddy toured the flood-hit areas of Kamareddy district. He inspected the Lingampalli Kurdu R&B Bridge, interacted with farmers in Budigida village whose fields were blanketed with sand dunes and walked through the devastated lanes of GR Colony. At the Integrated District Office Complex, he chaired a review meeting with officials. But for families that watched crops vanish, cattle drown and their savings swirl away in muddy torrents, the flood was more than a natural calamity; it was a reminder of how quickly life can be swept clean.