The quaint green village of Athimalaipattu, 14 km from Arani in Tamil Nadu, wakes up before sunrise. By dawn, the roads are alive with colour: long rows of silk threads stretched carefully from end to end, beaten gently to bring out their shine. Children run around, carrying ropes, sticks, and scissors, helping their weaver-parents with this centuries-old step known as street warping, after which the threads find their way to the loom, ready to be woven into a silk saree.

Learning from heritage artisans a must

“Why is this process done before sunrise?” someone asked, perking up.

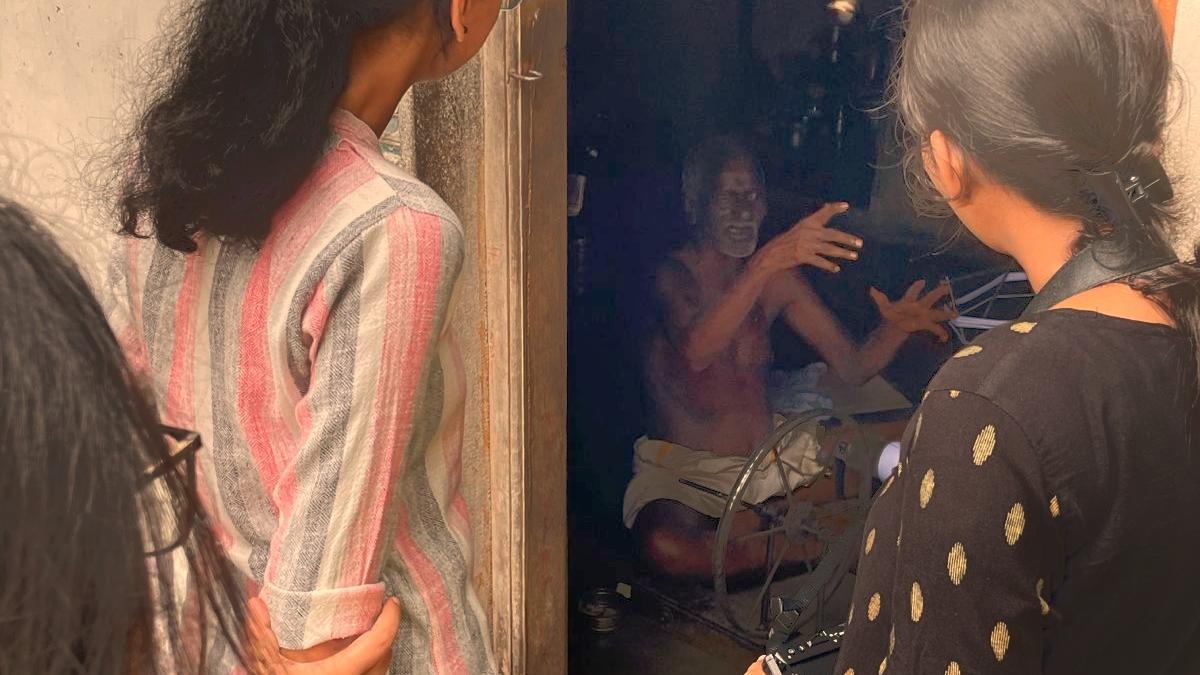

The question cut through the steady warping rhythm of a weaver. Doubts about his centuries-old family craft were unusual. “After sunrise, the heat will break the silk threads, and they will not be tensile and tight to be drawn as sarees,” he said, looking up. It was Swathini Ramesh, a student of the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), Chennai. She hurriedly scribbled his reply in her notebook as she was keenly observing.

Swathini and her 19 classmates, after completing their second year of Bachelors in Design (textile design), came and stayed in Athimalaipattu for a week to learn about their silk saree production as part of their Craft Research and Documentation component, as prescribed by the Union Ministry of Textiles.

“As part of their curriculum, students from all NIFT centres, including Chennai, visit craft clusters such as Arani that specialise in traditional crafts. This helps them to develop respect for the age-old arts of India,” said Professor Diya Satyan, Director, NIFT Chennai.

They are supposed to stay, work with the artisans, document the craft and present it as a report. “It helps to preserve and document heritage art and craft. Then, it gives the students the idea to take these traditional crafts to a new level. Then, in the final year, they go back to the cluster for a collaborative project and implement interventions – like how to utilise resources without affecting the environment,” said Associate Professor G. Krishnaraj, textile design department at NIFT Chennai.

Bringing classroom lessons to life

“This was the chance to see the theory of our classrooms come alive in threads and looms,” said Arushi Bansal, another student who visited Arani with Swathini. Although they had a loom in their classroom, seeing a full-sized handloom in Arani left them awestruck. “We did weave a cotton cloth, in the size of a handkerchief, in college. But it was not the real deal,” said Swathini.

“The ones in Arani were large and were in a pit,” said Arushi. A pit handloom is a traditional loom with a wooden frame, and it is used to weave silk or cotton. The weaver sits above a shallow pit in the floor. Pedals in the pit control the up-and-down movement of the warp threads (the long vertical threads), while the weaver’s hands pass a shuttle carrying the horizontal threads through them. By repeating this rhythm over hours, the threads slowly turn into fabric.

“I laughed when one of the students asked why the loom sits in a pit instead of on the ground. I explained that it allows me to work for hours without a break. Sitting above the pit with my feet inside makes it easy to operate the pedals, while my hands remain free to pass the shuttle and manage the threads,” recalled Venkatesan A, a 37-year-old weaver from the village. This loom helped his posture. “I don’t have to bend over the yarn and hurt my back.”

Arushi said she learnt more during the week with the Arani weavers than she had in two years of classroom study. “The hand-eye coordination these weavers have comes only from practice. If they have to transition to another colour in the saree, the weavers cut around 4,000 warped threads manually, then they take the other colour and knot it with the 4,000 ends before weaving. The hard work put into weaving a saree in a handloom was inspiring,” said Arushi.

Professor Krishnaraj said that saree designs cannot be done casually. “The students observed looms of different sizes and capacities. That’s when they could understand that only some looms allow two-inch-long designs, while others let designs with a length of four inches. There is no design that corresponds to one-size-fits-for-all.”

The students also visited the mulberry plantations and sericulture areas from where silk originates from silkworms.

Revisiting their learning centre

The Arani weavers are very hospitable people, said Swathini. “They gave us food, kept flowers on our head and even accommodated non-Tamil-speaking students in our batch. They taught me weaving in their handlooms too.”

During the seventh semester, the students are asked to go back to the clusters to work on a project. “I wanted to use natural and plant-based dyes to create a bridal wear brand with their silk. They agreed to send me the silk so I could dye it with natural dyes. They even kept a section for natural-dye silk sarees for sale in their cooperative society showroom,” said Swathini. “They encouraged me that promoting natural dyes is important because it is less hazardous to the environment.”

After college, Swathini started a brand and has an outlet in Thiruverkadu, Chennai and sells these natural dye sarees, sourcing silk from Arani, among different places in Tamil Nadu.

Arani silk is different, despite being an hour away from Kanchipuram. “Kanchipuram silk is a very heavy and traditional material. But Arani silk is more contemporary with modern motifs, mostly used for office and casual wear. Arani is also famous for checks (designs). These sarees also weigh less,” said Swathini.

Arushi, on the other hand, plans to collaborate with the Arani weavers to promote and popularise their production with social media and branding. “They gave a non-Tamil speaker like me so much love and care. They did not even speak English, but I could understand what they were communicating with some sign language and weaving practices. They opened up their houses, looms, and craft secrets to us.”

“The younger generation are gradually drifting away from our family and generational art. We want more weavers to join us. Our cooperative society offers handloom training with a small stipend too,” said Venkatesan.

Published – September 04, 2025 05:23 pm IST