India suffered a substantial net loss in forest cover between 2015 and 2019, revealed a new study conducted by researchers from Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay and SASTRA Deemed University.

The study said that for every 1 square kilometre of forest gained during the four-year period, the country lost nearly 18 square kilometres—an alarming ratio that underscores a significant fragmentation crisis in India’s forest ecosystems.

“While the Forest Survey of India (FSI) and other independent studies regularly report on India’s gross forest cover, there has so far been no systematic framework to understand structural connectivity and monitor forest fragmentation across the country,” the study said.

Led by Professor RAAJ Ramsankaran of IIT Bombay, and Dr. Vasu Sathyakumar and Sridharan Gowtham of SASTRA Deemed University, the study applied Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) to forest cover data derived from the Copernicus Global Land Service (CGLS) Land Cover Map. It offers one of the first country-scale assessments of forest fragmentation in India using publicly available satellite data and open-source tools.

A central feature of the study is its classification of forests into seven structural types, each with distinct ecological functions. Cores are large, intact habitats crucial for biodiversity and long-term stability. Bridges and loops enhance connectivity by linking cores or parts of the same core. Branches extend from cores, while edges mark their boundaries. Perforations are clearings within cores, and islets are small, isolated patches. The study finds that cores are the most resilient to degradation, whereas islets are highly vulnerable and prone to rapid fragmentation. Afforestation dominated by islets may have minimal ecological value.

Mr. Ramsankaran said, “Our resilience-based ranking offers a practical tool for policymakers. Rather than treating all forest areas the same, it helps identify which morphologies are most vulnerable (like islets) and which offer long-term ecological value (like cores).”

He added that afforestation programmes such as the National Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA) or the National Mission for a Green India can benefit by focusing on strengthening existing cores and building bridges between them, which could potentially yield better-connected, more resilient, and ecologically sustainable forests.

The framework also has the potential to inform infrastructure planning by helping identify areas where connectivity is most at risk, thus supporting more scientifically informed decisions and reducing ecological disruption.

Mr. Ramsankaran explained, “The framework relies on an image processing technique called MSPA to detect and classify the structure of forest landscapes.”

As part of the study, the researchers applied the analysis to digital forest cover maps of India for the years 2015 to 2019, obtained from the Copernicus Global Land Service (CGLS) Land Cover Map. Unlike most previous studies on forest cover, which report only net gains or losses, this study mapped forest loss and gain separately.

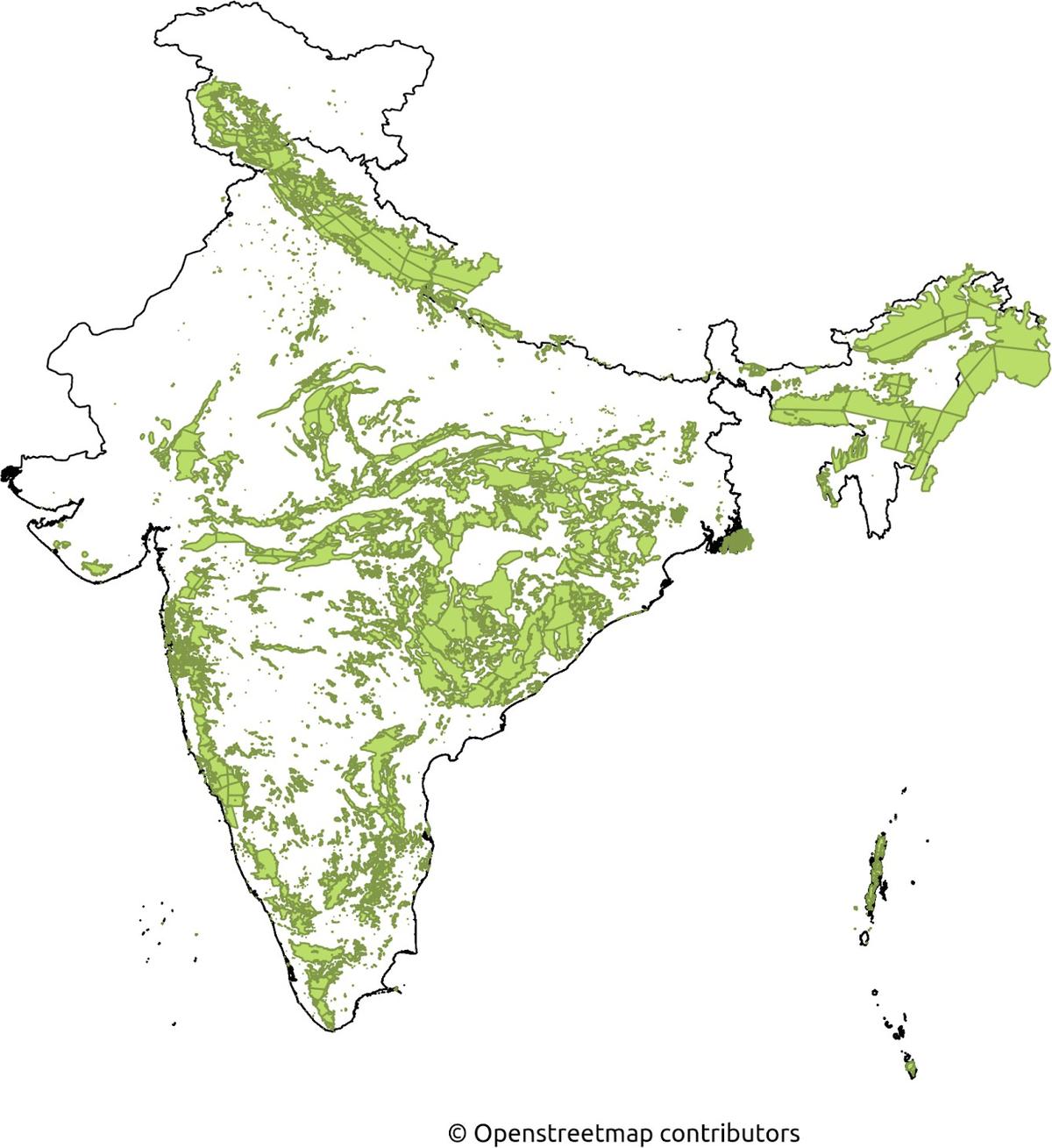

Indian forest cover map as of 2015.

“The results show that from 2015 to 2019, all states in India experienced a net loss in forest cover. Overall, India lost 18 square kilometres of forest for every 1 square kilometre gained. Nearly half of the 56.3 sq. km. of gross forest gain occurred in Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Rajasthan, while Tamil Nadu and West Bengal together accounted for almost half of the 1,032.89 sq. km. of gross forest loss,” the study said.

More significantly, over half of the newly added forest covers are islets, which do not substantially improve structural connectivity. This suggests that even where forest cover is increasing on paper, the ecological value and resilience of those forests may be limited.

Explaining the implications of the study, Mr. Sathyakumar said, “Our results clearly show that most of the newly added forests during 2015–2019 were islets, highly fragmented and ecologically vulnerable patches. There is a need to move beyond the current quantity-based afforestation approach and explicitly incorporate structural connectivity into forest planning.”

While the findings appear to differ to those of FSI, which often indicate an overall increase in forest cover, the results from FSI and this study are not directly comparable. FSI uses different criteria from the CGLS to identify forests and does not distinguish between fragmented and continuous forests. FSI defines forested areas as those with a minimum of 10% tree canopy cover and relies on satellite imagery with a 23.5 m resolution. In contrast, the CGLS dataset used in this study applies a 15% canopy threshold and a 100 m resolution. The researchers also had to rely on the internationally accepted CGLS dataset, as FSI data are not publicly available for similar analyses.

Mr. Sathyakumar said, “Since FSI reports do not include forest connectivity assessments, direct comparisons aren’t possible. However, our data source has a globally validated accuracy of over 85%, making our connectivity results reliable. If FSI’s data were made available in GIS-compatible format, our methodology could be readily applied to it.”

One limitation of the current study is that at 100 m resolution, narrow linear features such as roads and railways may not be fully detected, and forest fragments smaller than 100 m may be missed. However, the strength of the framework lies in its scalability, cost-effectiveness, and use of open-source tools. It can be expected to give consistent results with similar datasets at finer resolutions and can be applied at different spatial and temporal scales.

Mr. Ramsankaran said, “Our framework is fully extensible to finer scales, such as districts or protected areas, and can be used to analyse the impacts of linear infrastructure like roads and rail lines on forest connectivity in a more focused manner. This makes it a valuable tool for long-term forest monitoring, planning and informed infrastructure development in and around forested areas, both in India and in similar contexts globally.”

The researchers plan to further develop their framework to study local drivers of forest fragmentation and assess the effectiveness of current conservation and afforestation efforts.

Published – August 07, 2025 02:30 pm IST