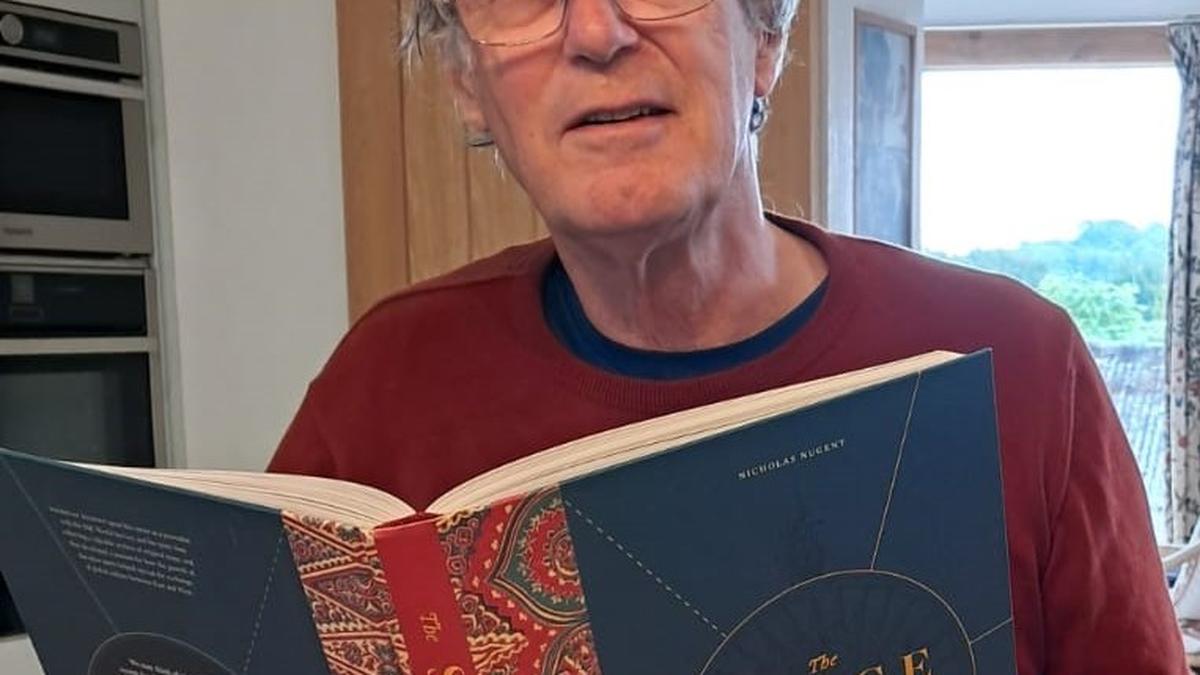

Journalists have an unending stream of stories to tell. Nicholas Nugent, who switched off his audio suite in the BBC as a broadcast journalist in 1999, continues to enthral listeners (in small conversations) and readers (of his seven books and the once-in-a-while newspaper column). Not with the “when-I-was-there” genre, however. In his elegant country house, overlooking farmlands and hills in Somerset, U.K., Mr. Nugent, author of The Spice Ports: Mapping the Origins of Global Spice Trade (2024), is at home with the world. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported from across Asia, is a regular visitor to India since the early days of Indira Gandhi’s premiership, and has authored Rajiv Gandhi: Son of a Dynasty (1990). And all along, he meticulously discerned the multiple impacts that arose from the spice age when the naval powers in Europe (where he hails from) were in competitive pursuit of these now ubiquitous flavouring agents in the Orient (where he worked as a foreign correspondent).

His 288-page book, with illustrations and ancient maps, published by the British Library in the U.K. and Brandeis University Press in the U.S., unravels the global impact of the spice trade. He also tells the stories of how this chase for zing gave to Mumbai and New York their present stature and provides a cameo featuring Madras. Two of his 10 chapters are on India’s west coast ports. The Malabar coast, he said, was one of the first places that the “Europeans latched onto as a source of oriental spices”. In an hour-long interview to The Hindu, Mr. Nugent connects the dots of how the several acts during the hunt for spices in the late-medieval period led up to the modern world. It all started with ancient mariners, the stars that guided them, map-making, and the monarchs who supported them. Excerpts:

May I start with your interest in maps? Journalists are interested in a lot of things. Why maps?

It was partly inherited from my father, who loved maps and lived in different parts of the world, and partly as I’ve travelled a lot. I’ve hardly stopped travelling since I first went to India aged 18. If one is interested in geography and places around the world, that immediately leads one to maps. I’m also interested in history, so if you put the two together, what you’re seeing around my house are antique, historic, and early maps.

What I like about early maps is that they’re so inaccurate. How did we get to the age we are today when maps have to have a high degree of accuracy? I like thinking about the age when, for example, early mariners didn’t really know how to get from one place to another. They used the stars, and only in, say, the 15th and 16th centuries did mariners report back and making maps became an industry in Europe and quite possibly in China as well. It’s quite hard to know. That’s the story I’ve told in The Spice Ports.

Pioneers, like Vasco da Gama and Christopher Columbus, didn’t have maps; they gave rise to the industry that created them. It’s those maps that I like because I like the notion of collecting the material for the maps, and when I acquire the maps, I like to try and read the story or the history that is behind them.

On the geography as well?

Geography, of course, to point out the inaccuracies at the same time.

There are three undercurrents that can be inferred from your book: shipping, trade, specifically in spices, and colonisation. How would you triangulate them?

Well, I absolutely agree with you that they go hand in hand. One fed the other, as it were. I concentrated on the maritime trade, first of all, and how did ship builders create the ability to travel long distances, so I tend to come to it from that point of view. I would look at the three ingredients that gave rise to maritime trade slightly differently.

First, shipbuilding. You had to have the technology and indeed the materials to build ships. The way I told the story, the Venetians were dominating shipbuilding in Europe, until suddenly the Portuguese were building better ships. And then they lost out to the Dutch. So, the first ingredient is shipbuilding.

The second is maps. ‘Do you know where you’re going?’ And that also helped the Portuguese because they sailed around the southern tip of Africa, proving that the Indian Ocean was not surrounded by land. I can show you a map from the year before Vasco da Gama sailed that I have. It shows the Indian Ocean completely surrounded by land, and even 50 years [after that], maps were produced showing land all around the Indian Ocean. Now, if Vasco da Gama had depended on that 1496 map, he would not have got there, would he? He never would have set sail. So, map-making was the second ingredient.

And the third was technology, like astrolabes and compasses, and the technical side of finding your way.

So where does the commercial interest come in here? Why spices? Was it serendipity or was it a felt demand?

Well, I’ll tell you what I think happened, and bear in mind we’re talking about European trade with Asia. What I think happened was that in the place of origin [of the trade routes], people were getting quite excited by spices, by flavouring.

Let’s face it, cooking, wherever, was quite bland in the 15th Century and spices spiced it up, literally. Made it more attractive. So, let’s assume that was happening in India, in what we now call Indonesia, and perhaps in other places in Asia, and some wise mariner, either from India or from the Middle East, was shipping these spices over to the Arabian Peninsula and the Red Sea. And from there they were being trans-shipped through ports like Alexandria, and the Venetians picked them up from there because, having tried it once, they found there was a market for it in Europe.

Venice was the first market for spices in Europe. That’s why the Venetians kicked off long-distance trade in spices coming to Europe and made a lot of money out of them. As islanders, Venetians had to use ships to bring even their basic needs from the neighbouring land; spices came from further afield. Venice was also a great shipbuilding nation with quite a long history, especially for fighting the Crusades against Muslims in the Middle East, so it is quite obvious to me why the Venetians started the process off by trans-shipping spices from Alexandria to Venice.

By the time the Portuguese from Lisbon found their way around the Cape, they bypassed the Middle East and took over from the Venetians. They had an enhanced understanding of geography, hence map-making, and they found their way to the sources of spices, initially to India, because even spices that came from further East were brought to India. There was lot of short termism until Vasco Da Gama showed the way. And the story goes on from there.

Though you talk about the past, there is a ring of the contemporary in it, such as the emergence of supply chains, entrepot trade, and trans-shipment. How would you place the ports along the Malabar coast? Were they for trans-shipment or ports of supply, or a bit of both?

Well, both, definitely. It’s no accident that Vasco da Gama ended up on the Malabar Coast because that’s where the currents and the winds took ships that came from Europe. Fortunately for them, it was the home of spices. Kerala, even today, is rich in spices, so it was an introduction to oriental spices.

In a port like Cochin, you could also get spices that came from further afield from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where there was better cinnamon than what was cultivated in Kerala, but most especially ginger. I’m not sure if ginger is indigenous to India, but ginger was certainly coming from China. Spices that were definitely brought in from further East were clove, nutmeg, and mace, and they were all brought to India. I can’t tell you exactly where, but Cochin seems to feature quite prominently as a source of spices because it produced its own from the Kerala — or Travancore — hinterland. The Malabar coast was one of the first places that Europeans latched onto as a source of oriental spices.

Let’s travel further north to Goa. It’s remembered more for colonisation. What was the Portuguese interest in Goa?

Well, I think you put your finger on it because Goa is not, as far as I know, spice-producing territory. So why would they go there? And the story of the Portuguese capture of Goa, which is what it was, seemed to be a decision taken by Affonso de Albuquerque — the Portuguese viceroy of Malabar, or whatever the terminology was at the time. He was given a brief to expand the early Portuguese Empire, and he latched on to Goa because it’s an excellent port. I mean, we’re already talking about colonisation, aren’t we? He fought and defeated [the forces loyal to the Bijapur monarch, Yusuf Adil Shah], effectively taking over not just Goa but the trade in spices between India and the Arabian Peninsula.

You were right to introduce colonisation because I believe this was a crucial stage in colonisation. In other words, European takeover of territories in distant places to which they had no right. But it was power, wasn’t it? It was power, and they were making money. They were meeting a demand for spices in Europe. Also, it was the Portuguese getting one up on the Venetians. Ultimately, it was the European demand for spices that seemed to drive the trade and Goa was, in a way, accidental. But it became the important foothold of the Portuguese in India and they exploited it by moving in and taking over and capturing the spice trade, both the spices which were indigenous to India and that were being trans-shipped from further east.

Let’s look at another colonising country, France. So, the Dutch, the Portuguese, and the French were fighting for the Indian Ocean. How did this play out and when did the English come in?

I would portray it slightly differently because the French were very small in Asian terms, but yes, they were competing with the Portuguese, the Dutch, the English, and even the Danish for a little bit of territory in India. As is well known, the French had a battle where they had a rivalry with the English, especially over Mauritius, and they ended up with small amounts of territory, mainly in southern India but they were never big traders with India.

Their colonial history is much more to do with parts of West Africa, and indeed Indo-China – Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos – which came much later. The biggest early French imperial involvement in Asia was in Mauritius, and indeed, that was quite successful, especially with sugar trade. I brought Mauritius into the book because it’s quite significant in terms of the spices being trans-shipped [and] they also made a great thing out of the sugar industry in due course. But it is also relevant to colonial history in southern India, especially the stand-off between the English and the French over Madras and Pondicherry [for three years, which ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle in 1748, after which the English regained possession of Madras.] You also have an interesting chapter on Bombay, what’s now called Mumbai.

You also have an interesting chapter on Bombay, what’s now called Mumbai.

Well, if you’re looking at colonial history of India, you can’t but take a close interest in Bombay, as I continue to think of it. It was successively ruled by the Portuguese, who didn’t make it pay. It was a bunch of seven islands in Portuguese times. They built a Catholic Church on each of the islands, but they didn’t get much else out of it.

In a curious historical event, [in 1662] it was part of the dowry from the Portuguese to the English on the marriage of Charles II to Catherine of Braganza in Portugal. So that’s how the English acquired Bombay, again, iniquitous – one European country gives this port to another country. But let’s put in a good word for the English because they made it into a city, they made it into a major port, and they made it pay. You could argue that Bombay wouldn’t be the Mumbai of today if it hadn’t been for English commercial interest in not just spices, but by this time, many other things and colonisation in India took off big time.

They started in Surat but they dabbled in Bombay and Madras. And then Bombay became big. But ultimately, Calcutta became the biggest place. So English history of colonisation of India is about really those four major places.

If I may cross the globe again, to the formation of the company, to how decisions were taken in a faraway place about the movement of commodities, formalising what we call in modern terms, the [joint-stock] company. Could you elaborate on these developments?

When the Portuguese made a big thing of long-distance trade, it was financed by the monarch, as did the Spanish. They funded these expeditions, gained the profit, and presumably paid the sailors a little bit, but the large [share of the] profit accrued to the monarch of the time.

The Dutch were the dominant force before the English. They effectively invented the joint-stock company, which meant that anybody could invest, and anybody could claim a share of the profit, which was paid in spices. So, you put in your Guilders, or whatever the currency was or your bit of silver; when the ship came back, if the ship came back — not all survived, you see — then you got a bunch of nutmeg that you could take to market and sell for currency quite successfully

They also introduced the stock market. So, if you got a share in an expedition and you needed money in a hurry, you went to the market, which was the quay, the waterfront, and you sold your share. That was the origin of stock markets. They also introduced banking because it’s all tied up, so the Dutch really pioneered those three things. Incidentally, newspapers also originated around this time in the Netherlands. So, Amsterdam was key to all those things.

The Dutch and the English had started trading long-distance about the same time, and initially Queen Elizabeth I of England was the major investor, rather like the Portuguese and the Spanish monarchs had been. But then she gave a Charter to the East India Company. So, in effect, they were around the same time as the Dutch but just after them. They were following the same notion of making the funding of long-distance trade open to all. You would say that it’s the introduction of capitalism.

Could you say that the raw materials from the Far East and its demand for them in the West were the parents of modern capitalism, so to say?

Both modern capitalism and modern international shipping trade. They’re both the means for doing it. You could take this further and say democratisation, in the sense of taking power from the monarch and giving it to the ordinary people, or at least an elite, a wealthy elite. But yes, I think you’re making absolutely the right connections.

Early oriental trade and specifically spices, but not exclusively spices, because tea and coffee, and later rubber, are part of the story. Early trade in commodities gave rise to the shipping industry and also gave rise to the means of financing it and the whole banking structure.

You could take a step back and say even currency, because you needed money, you needed something to buy your goods with, and either you shipped something out and traded it, or you bought it with pieces of silver. The Venetians used Ducats for example. You had to have some form of currency or commodity the East wanted in the early days.

Would it be the case that it was early oriental trade that gave rise to the modern globalisation?

That’s a slightly greater claim than I would make. I’m only presenting the Orient and oriental spices as one example because, for all I know, there were other things. I’ve already mentioned coffee. And, initially, rubber as well. So, if you take the word ‘oriental’ out, I would certainly agree that trade in basic commodities was the early stage in long-distance international trade.

And that also goes to another interesting aspect that you touch upon, which readers would be surprised to see in a book on spices and ports — about the Law of the Seas… how the seas were regulated during this ‘spice age’.

You’re spotting all the key things that I’ve tried to bring into this story. I would argue that the laws of the sea originated in Malacca in Malaysia, because they had a system of trade that they tried to refine in detail as trading rules. The Dutch were then in control of Malacca, and a Dutchman Hugo Grotius, the originator of laws of the sea really, based it on the Malaccan system.

The name of the term in Malay is hukum laut or sea law. Grotius was the man most associated with drawing up early laws of the sea. Before that, it was a free-for-all. I have a picture [one of the several maps and illustrations that line the walls of his house] of the Dutch and the Portuguese fighting for control of Cochin. War was the early law of the sea. Grotius’s 1625 treatise, De Jure Belli ac Pacis (On the Law of War and Peace), has a better claim to be the origin of laws of the sea than almost anything else.

I don’t want to go deep into sea piracy but there is that connect there as it ties into the role of the state…

Piracy is a very curious concept. Who are these buccaneers who come from distant lands and try to make claim on what is produced there? But I think you’re referring to the out-and-out brigands who pounced on the ships coming into certain harbours. They were very active in the west of India, where trade was lively with West Asia. In the Arab world, piracy was absolutely rife and part of finding your way was trying to avoid the pirates.

But these are sailing ships, so you also needed to know about the winds because it’s only the wind that would get you there without your maps, your navigational instruments, or your powered vessels. Wind was the power. Can I say something more about wind?

Yes. Please.

Wind was how the Dutch took over from the Portuguese because they were the great windmill experts. They built windmills. Once they drained the land for the early Dutch people — as a very small nation, they needed somewhere that wasn’t waterlogged for people to live — they adapted windmills for other purposes, one of which was to create sawmills driven by wind. They were cutting wood by wind power. Just imagine they built their ships more cheaply and quicker than the Portuguese and they took over the long distance [trade].

We may think wind power is an invention of recent years to create electricity, but the Dutch could drive a sawmill very powerfully from wind and build ships that could defeat the Portuguese in the eastern trade. If you don’t believe me, go north of Amsterdam, and you can see that there is still in use a repurposed windmill that is a sawmill. And you go into that sawmill, and you think this must have electricity running it because it’s so fierce, so effective, but it is entirely driven by wind.

Your book is not only about moving commodities. There is a consistent subtext on society and individuals. Could you talk about the period and its big names?

Yes, well, I’ve tried to tell the oriental spice story alongside what else was happening in those countries. We’ve talked about how spices gave rise to banking and stock markets. Here’s another example: the Dutch Golden Age with its famous artists. Is it a coincidence that that began at the same time that the spice trade started in the late 16th century?

On the scientific sphere, two other things happened in the Netherlands: one was the study of anatomy which features, as it happens, in Rembrandt’s paintings. So, there was investment in that sort of scientific research. Anatomy and surgery advanced to a high degree in the Netherlands.

The other thing is the lens. Now the Dutch are good at polishing diamonds but it all started with polishing lenses. They invented the telescope and the microscope, as far as my historical research suggests. The telescope was low-level until it was taken to Venice, and Galileo picked up the telescope, selling it to sailors. They were the early users of telescopes but it was a scientific development in the Netherlands that gave rise to it. So, everything goes round in circles.

I’m saying that trade and the profits from trade gave rise to the scientific research and exploration, as well as the arts, especially painting and literature. They all flourished when the nation was making money or people in the nation were making money from the spice trade. It’s no coincidence. How did Europe get rich long before Asia? Because they found a trading formula of bringing in commodities and making profits, and I’m talking big profits if you’ve got mace, which comes from the nutmeg plant, it’s the outer core of the nutmeg. The Dutch were at one stage making something like 3,000 per cent profit on mace brought from the East Indies to Amsterdam. Gosh!

So, we could go back to the situation of three things, at least, that were generated by long-distance trade, initially in spices. One was the arts in general; another was science, and the third one, which we’ve already mentioned, was banking and stock markets. All were closely related, so we cannot really look at maritime trade in isolation. It gave rise to so many other things.

I had in mind Issac Newton as well…

The scientific expertise moved from Galileo [in what is now Italy] to Christian Huygens in the Netherlands and then to Isaac Newton in England. There’s a scientific line that in my book begins with Copernicus [in Poland], who first proclaimed that the Earth rotates around the Sun rather than the other way round. Galileo popularised this theory and got into big trouble with the Catholic Church while he was making money selling telescopes to the sailors. Galileo was a very significant figure.

Then it moved to Huygens in the Netherlands, who was a pioneer of lenses. And then it came to Isaac Newton, who famously discovered gravity. This was the time when London was taking over from Amsterdam as the big trading centre and Newton, interestingly, having made a bit of money by his discovery [of gravity] and teaching at Cambridge University, then invested his money into further trading ventures, which he didn’t do particularly well, and then became the head of the Royal Mint. He is an interesting historical figure and is the reason Britain joined that scientific pedigree. But Britain joined in another way: John Harrison, who invented the chronometer. In other words, the way of telling the time at sea, which was absolutely crucial to navigation.

The Prime Meridian, Greenwich…

Then Greenwich took over as the as the centre of the world, you could argue. So yes, there’s that scientific undercurrent going there. I’m sure I could mention some other names, but we’ve got the key ones there that are involved.

I’m going to stay with names for some more time because your book also gives the readers thoughts for further interconnections. You call your opening chapter, ‘The Merchants of Venice’, in effect, giving trade a persona based on Shakespeare’s famous play. What other interconnections with literary figures do you mention?

I refer to Bertolt Brecht’s 20th-Century play, The Life of Galileo, which brings out the soured relations between the church and science after Galileo’s discovery. The other two writers I would think of are much, much less well known but they also are relevant to the overall story.

One is a Dutchman in Indonesia, Eduard Douwes Dekker, who wrote under the pseudonym Multatuli. He was a coloniser, but he also helped bring an end to the rather brutal form of trade and colonisation that the Dutch exercised in Java, whereby the Dutch decided what the local farmers should grow and also decided how much they would pay for it. I like his novel, Max Havelaar (1860), because it changed the way the Dutch operated.

And there’s another novel which changed the way the French operated in Mauritius and other colonies. Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s novel, Paul et Virginie (1806), is a love story as well as a satire which also argued against slavery and for social justice. It got its place in French Literature, and it changed French colonial policy towards Mauritius. I like books that either told part of the history story, or in those two cases, one for Indonesia and one for Mauritius, actually changed policy.

Before we conclude, I’d like to touch upon the U.S. You also discuss Manhattan and Salem. What was the position of the U.S. in the supply chain?

Well, the U.S. at that time was a colony no different from India or Indonesia. It was a colony mainly of the English who were trading with North East America. I brought it into my story for two reasons. New York was not a spice port as such, so why have I brought it in? For a very curious historical fact.

Remember, the Dutch and the English were big rivals in the colonising business. The Dutch had control of the East Indies or Malay Archipelago, and they had control of what we now know as the Spice Islands. Roughly 1,000 islands that included the world’s sole source of nutmeg and of cloves and mace, and they were laughing all the way to the bank because they were making fantastic profits from these commodities in Amsterdam, but for one thing, nutmeg grew on eight islands and the Dutch only had control of seven of them. And the English had control of the eighth. That broke the Dutch monopoly. The English were getting out nutmeg and mace, and undermining the Dutch East India Company, the VOC, [the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie] and their ability to make profit. So, they [the Dutch] were quite angry about this and they were having battles against the English in the North Sea.

A Dutch raid on the naval port at Chatham in Kent in 1667 destroyed a lot of English warships, after which they got together and carved out a deal which involved effectively swapping territory. By July 1667, the Dutch, as it happened, had control of this one island, Pulau Run, in the nutmeg group of islands [Banda Islands]. They’ve got their monopoly back or they thought they had. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the English had gained control of a piece of territory that the Dutch had before: the island of Manhattan, or today’s New York. They actually got more than just the island, the whole New York hinterland! So, in 1667, the Dutch were happy that they got their nutmeg monopoly back. The English were happy that they’ve got New York. But frankly, the Dutch had not been making a profit on it, like Bombay with the Portuguese, so who got the better of the deal? History shows us that the English did rather well on that deal.

I might say this is not a direct swap, and there was other territory involved but the important ones are Pulau Run in the Moluccas, part of the Dutch-ruled East Indies, and Manhattan. Unfortunately for the Dutch, nutmeg had been transplanted by both the English and the French – nutmeg now grows in quite a lot of other places – so they had lost their monopoly forever, but they didn’t know that at the time. That’s why New York features, because of this bit of history.

Up the coast from New York in Massachusetts is a port called Salem, famous for its history of witches and the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, and much less well known for its early maritime trade in peppercorn. The merchants of Salem built good ships, I believe they were the first to build copper-bottomed ships which gave much greater staying power, a metallic outer surface to the wood. They sailed across the Atlantic Ocean around the Cape and across the Indian Ocean to Sumatra, where they found a ready trade in the spice peppercorn. They were rivals of the Dutch, but the Americans, as we shall think of them, the Salem mariners went further north, where the Dutch didn’t have complete control to the area we now know as Aceh. From there they were getting most of their peppercorn.

Peppercorn, by the way, is a spice that originates from India. Yet by the time we’re talking about it had been transplanted to Sumatra, and the first American millionaires were the traders of Salem. Remarkable! And you know, we’re talking about the days when one port specialised in one commodity. Salem got rich on peppercorn. I’m sure they brought other things in the ships but peppercorn is what brought the profits. Rather like nutmeg did to Amsterdam.

Finally, to try to tie all this up from the then to the now, these remind me of Adam Smith, whom you mention in your book as well.

Adam Smith more or less invented the study of the social science of economics. And he was a critic of monopolies. He helps us understand the story because that’s what economics does today. We are more or less driven by notions of economics, and you’ve already mentioned the ‘supply chain’. When I studied economics, it was all about how price was determined by supply and demand. We owe Adam Smith credit for helping us understand what was going on. He first used the term ‘monopoly’ to explain why certain forms of trade produce massive profits, because no one else had got access to it. And the story starts with the fact that nutmeg came from only eight small islands in the world and clove comes from a different set of eight small islands. And the race starts there.